Meet the “artificial embryos” being called uncanny and spectacular

The stem cells live only a few days, lodged between tiny pillars on the surface of a microfluidic compartment. Yet during that time, stop motion video shows the cells multiplying, changing, and organizing themselves into hollow spheres.

They are following their ultimate program—to try to turn into an embryo. And they are doing a startlingly good job of it.

Today, researchers at the University of Michigan are reporting that they’ve learned to efficiently manufacture realistic models of human embryos from stem cells. They think the advance will let them test fertility drugs and study the earliest phases of pregnancy, but it is also raising novel legal and ethical issues.

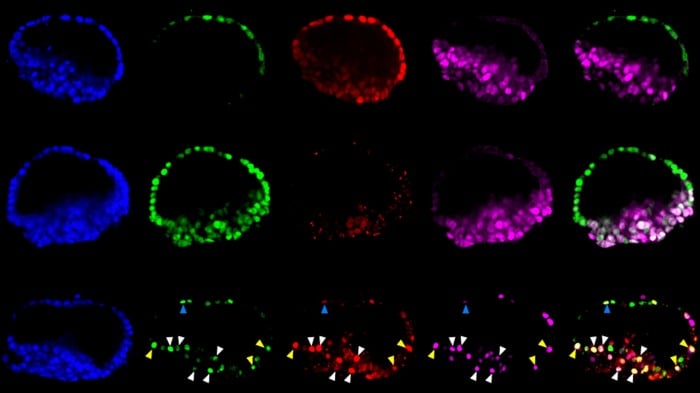

The artificial embryos were made by coaxing stem cells to spontaneously form tiny ball-shaped structures that include the beginnings of an amniotic sac and the inner cells of the embryo (the part that would become a person’s limbs, head, and the rest of their body) though they lack tissues needed to make a placenta.

“It’s uncanny how much it is like a human embryo,” says Alfonso Martinez Arias, a geneticist at the University of Cambridge who is familiar with the research findings, published today in the journal Nature. “This one is particularly spectacular.”

For now, scientists say, these aren’t true embryos and lack the capacity to turn into a person. However, as similar research races forward in Europe and China it is raising questions about how close scientists really are to synthetically creating viable human embryos in their labs.

So far, teams have been able to coax stem cells into recapitulating several key early parts of the embryo’s journey, such as forming the beginnings of nervous tissue and sperm or egg cells and making early decisions like what’s going to be an animal’s head and what will be the tail (see “10 Breakthrough Technologies 2018: Artificial Embryos”).

The ones developed by the Michigan team, which was led by bioengineer Jianping Fu and biologist Deborah Gumucio, were only allowed to live four days and don’t have all the cell types needed to qualify as a real conceptus, as the implanting embryo is known, and are likely to have other abnormalities and limitations.

But scientists believe that it might not be long before they can synthesize embryos in the lab that are almost indistinguishable from naturally created ones. Already, research on artificial mouse embryos has progressed to the point where scientists are transferring them to female surrogates and trying to make live animals, though they haven’t succeeded yet.

The concern is that if scientists could make human embryos in the lab, someone might use the systems to generate genetically modified people, a dystopian scenario similar to the central hatcheries described in the novel Brave New World.

Last December, Martinez Arias joined Fu and several others who wrote an editorial calling on regulators to permit scientific research with the models but enact a legal prohibition on using them to try to start a pregnancy. “We urge regulators to ban the use of stem-cell-based entities for reproductive purposes,” they said.

Fu says only someone “crazy” would try to make a person using a synthetic embryo. However, given the rapid advance of the science, he sees a legal ban as important. “Many scientists are trying to push boundaries, and people are crossing lines. If you let scientists self-regulate, that is how the gene-edited babies happened. I don’t trust self-regulation,” says Fu.

Here is how they did it

It’s known that stem cells left in a dish will spontaneously turn into heart muscle and start beating. As well, there are blob-like brain organoids that emit electrical waves, and mini-guts that can be used to test whether drugs work.

The new research goes further, efficiently mimicking an embryo’s opening days of development. According to the report, Fu’s team placed individual stem cells into tiny slots on a microfluidic chip, and then provided chemical cues that helped them start dividing and taking the shape of an embryo.

The Michigan team, whose preliminary results made the news in 2017, now say they can get the stem cells to turn into embryo-like structures more than 90% of the time, and that they’ve made hundreds of them.

“This is the new standard for controllability, which makes it into an experimental platform,” says Fu. “Each channel has many chambers, and each can trap a little ball of pluripotent stem cells. Chemicals only reach one side of the ball, so when and where the stem cells are stimulated is very controlled.”

To developmental biologists—those who study how bodies form—systems that model the human embryo are cause for keen excitement. Fu says teams in Japan and the UK are already using the Michigan microfluidic device to investigate how certain cells in the embryo get designated as future sperm or eggs cells. If they can determine that, it could lead to ways to make reproductive cells for people who lack them.

Funding confusion

The rapid development of embryo models is posing a challenge to the National Institutes of Health, which isn’t sure it can fund this type of research because of a law that forbids it from paying for experiments involving human embryos. That law, the Dickey-Wicker Amendment, is written to say any human “organism” made from cells would count as an embryo.

Because it’s not obvious what qualifies as an organism—that term means a life form, but isn’t defined in the law—the agency has started passing grant applications from researchers like Fu to a special “human embryo research steering committee” staffed by agency officials that will determine whether they would violate the statute.

“We don’t have a funding policy, but we need to judge each grant that raises concerns,” says Carrie Wolinetz, associate director for science policy at the NIH. “They can say [this] poses too great a legal risk.” She agrees the question is whether embryo-like entities such as the ones Fu is creating “could constitute an organism or not,” adding that “this is a very rapidly evolving area of research and science and we want to understand it.”

To do that, the NIH is participating in a one-day workshop, planned for early next year at the National Academies, in Washington. The workshop’s goals include trying to identify “differences between mammalian embryo model systems and bona fide mammalian embryos.” As well, the International Society for Stem Cell Research, a scientific organization representing stem-cell biologists, says it will be addressing the lab models as it revises its guidelines for scientists.

Politics can’t keep up

The funding confusion, say scientists, has been compounded by recent federal policy changes that limit money for research involving abortions. In June, the Department of Health and Human Services said it would end all government research employing fetal tissue from elective terminations. It may still fund academic scientists, but only after an involved ethics review.

As part of the clampdown, which most ascribed to abortion politics, HHS said it would be working to “ensure” that alternatives to fetal tissue “are funded and accelerated” and indicated it would prioritize models that mimic embryos. However, when a branch of the NIH issued invitations to apply for money to develop fetal-tissue alternatives this year, the solicitation specifically excluded “human embryo model systems” made from stem cells.

Scientists say such contradictions show that funding is being influenced by politics. “It’s bizarre—brain organoids are fine, but vaguely embryo stuff is not,” said one researcher, who wanted to speak off the record because he has pending grants.

This week, in a separate report, a team at Rockefeller University described how they’d mimicked groups of cells whose organization is similar to the early formation of the brain, nervous system, and skin of a month-old embryo. At that stage, a human embryo is a minute shrimp-like structure with tiny limb buds.

The Rockefeller researchers, led by Eric Siggia and Ali Brivanlou, call their structures neuruloids. They say because of the “difficulty” of obtaining or studying actual human embryos at this early stage, they judge their technology the “only practical solution.” They have formed a startup company, Rumi Scientific, that plans to screen drugs on the neuruloids for conditions like Huntington’s disease.

Siggia calls the government’s shifting positions a sign of its “current state of confusion” as it attempts to figure out “what is an embryo and what is not.” But he says his research is unaffected: “We are not slowed down by any of this. We just use private funds.”

Deep Dive

Biotechnology and health

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

An AI-driven “factory of drugs” claims to have hit a big milestone

Insilico is part of a wave of companies betting on AI as the "next amazing revolution" in biology

The quest to legitimize longevity medicine

Longevity clinics offer a mix of services that largely cater to the wealthy. Now there’s a push to establish their work as a credible medical field.

There is a new most expensive drug in the world. Price tag: $4.25 million

But will the latest gene therapy suffer the curse of the costliest drug?

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.