Four tech takeaways from the climate town hall

Ten US presidential candidates expounded on the dangers of global warming and details of energy policy on cable television last night. For seven hours!

The fact that CNN’s climate town hall happened at all offers one of the most concrete signs yet of just how far and how quickly US public and political sentiment has shifted. Climate change scarcely came up in the presidential campaigns or cable coverage four years ago. But this time around Democratic candidates have scrambled to outbid one another in announcing plans with bigger dollar figures or faster timetables.

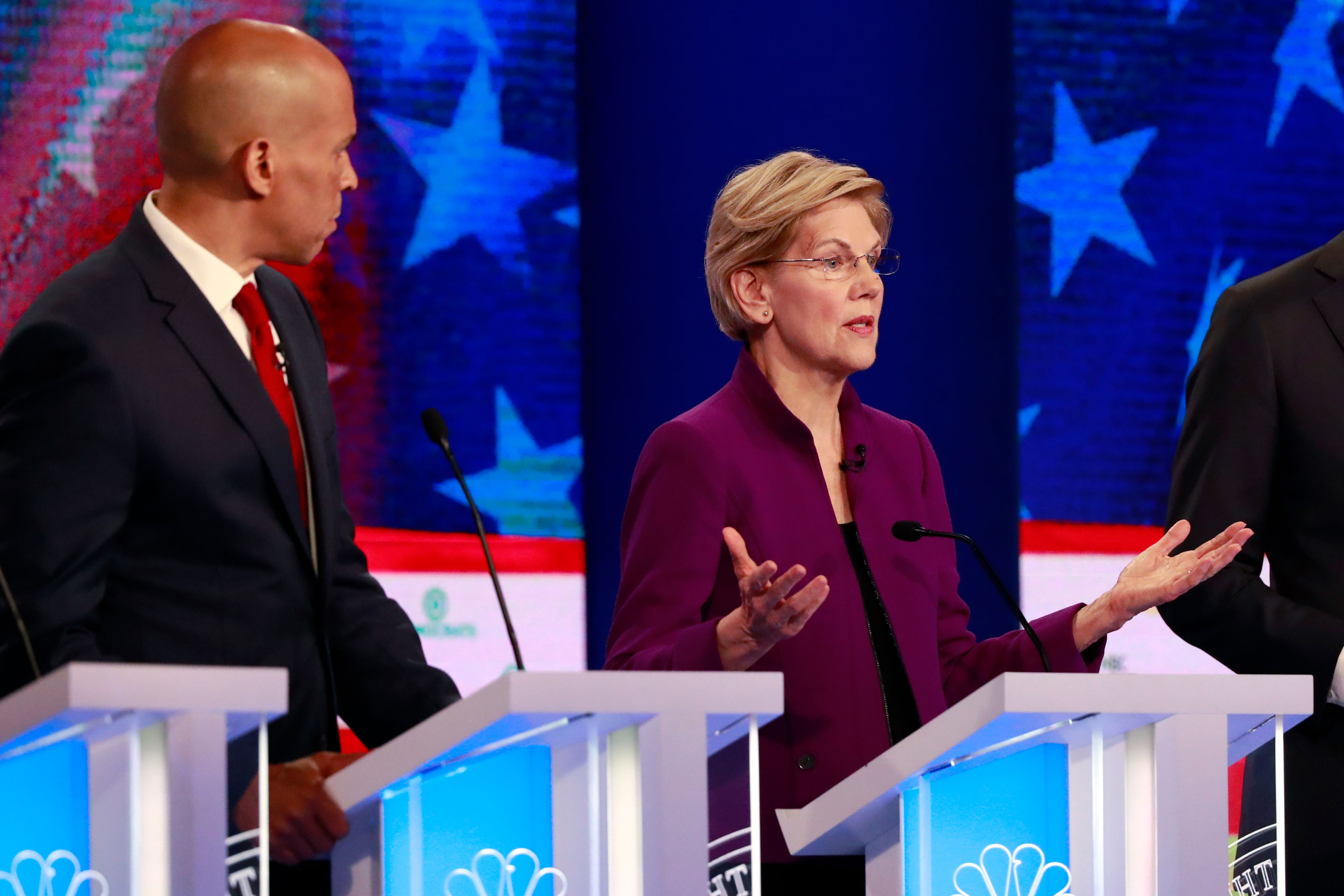

To be sure, CNN flubbed it at times. Some of the network’s moderators didn’t appear to understand how a carbon tax or federal R&D funding works. They also seemed really eager to echo Republican talking points about nanny-state regulation of straws, cheeseburgers, and light bulbs, a fact Elizabeth Warren appropriately scolded one anchor for.

Still, notes Leah Stokes, an assistant professor of political science at the University of California, Santa Barbara, it was “unprecedented and amazing” that millions of Americans got to hear presidential candidates talk at length about the escalating dangers of global warming, and their competing ideas about how to address them. She and others credited the Sun Rise Movement, a youth-led activism group, for creating pressure that helped make it happen.

Here are three other things that caught our eye from Wednesday night’s town hall:

The deepening Democratic split over nuclear power

Warren surprised some by coming out strongly against nuclear power, saying she would stop construction of new plants and eventually work to phase out existing ones.

That’s a bad idea. Nuclear provides around half the carbon-free electricity in the US today, so shutting down reactors would greatly complicate the task of decarbonizing the power sector in the next few decades. For fluctuating energy sources like wind and solar to replace nuclear and fossil fuels, there would almost certainly need to be some kind of cheap, long-duration energy storage technology to smooth out peaks and troughs in supply—and that technology doesn’t yet exist, as we’ve written about at length (see “The $2.5 trillion reason we can’t rely on batteries to clean up the grid”).

Cory Booker stressed this point during his session, saying: “People who think that we can get there without nuclear being part of the blend just aren’t looking at the facts.”

Another candidate, businessman Andrew Yang, has also been a vocal advocate of nuclear, arguing in his climate plan that the nation should invest $50 billion in R&D funding to accelerate the development of safer next-generation technologies.

Geoengineering’s public moment

Yang would also earmark $800 million for research into geoengineering—the idea of cooling the planet by using various technologies to reflect away more of the sun’s heat. His plan mentions “launching giant foldable mirrors into space” as a possible emergency response.

(See “What is geoengineering—and why should you care?”)

Whether we can safely research geoengineering, let alone conduct it, is still hotly debated within academia. And it’s not remotely a mainstream idea in the US yet.

But Yang said on stage that space mirrors (by the way, not the approach most academic researchers are focused on) should be part of the climate debate. While stressing that geoengineering shouldn’t be the “main approach,” he added that “in a crisis, all solutions need to be on the table.”

Surprisingly, the topic came up again later in the evening. Alan Robock, a Rutgers professor who has published a list of risks of geoengineering, asked Booker what he thought of the idea. Booker, to his credit, simply said he didn’t know enough about it to take a firm position.

What to do about natural gas?

Natural gas, which produces about half as much carbon dioxide as coal, is a conundrum for climate goals. The US Energy Information Administration has found that switching from coal to natural gas—it now generates 35% of US electricity, versus about 27% for coal—has helped decrease US greenhouse-gas emissions in recent years.

But those gains seem to be petering out. Weather conditions and economic growth last year led to the biggest leap in energy emissions since 2010, and a rise in use of natural gas accounted for most of it. Recent research also suggests that methane leaks during natural-gas drilling are higher than previously thought. Methane is a much more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, at least for the first few decades, so a small increase in it could wipe out any emissions advantages gas has over coal.

Democratic candidates are split on what to do about natural gas. As the New York Times noted, Bernie Sanders, Kamala Harris, and Warren have all called for a ban on fracking. In contrast, former vice president Joe Biden only wants to halt new drilling on federal lands, while Amy Klobuchar stressed that it’s still “better than oil.”

Natural gas might be a viable long-term power source if gas-fired power stations add systems for capturing their emissions. Many in the energy industry are closely watching NetPower, a startup testing a new type of gas plant that may pull that off at competitive costs. That could let utilities keep using a cheap and highly flexible energy source that helps balance out the vagaries of wind and solar. (See “Potential carbon capture game changer nears completion.”)

Others say a gas ban could have the unintended effect of reinvigorating the coal industry in the short term, pushing up emissions further.

Of course, climate plans and town hall pronouncements are all just words. We don’t yet know who will make it into the primary, who the next US president will be, or which party will control Congress. Whatever the candidates’ plans, what will matter most is their ability to convert them into laws that rapidly cut emissions.

Deep Dive

Climate change and energy

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Harvard has halted its long-planned atmospheric geoengineering experiment

The decision follows years of controversy and the departure of one of the program’s key researchers.

Why hydrogen is losing the race to power cleaner cars

Batteries are dominating zero-emissions vehicles, and the fuel has better uses elsewhere.

Decarbonizing production of energy is a quick win

Clean technologies, including carbon management platforms, enable the global energy industry to play a crucial role in the transition to net zero.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.