Computer science reveals why this headline is not funny

Humor seems to be an inherent part of the human condition. Our ability to smile, laugh, and giggle plays an important role in social situations; that piques the interest of sociologists and anthropologists. But you have to “get” a joke before you can laugh, so humor is also of interest to cognitive psychologists.

That immediately introduces a potential role for artificial intelligence. So computer scientists have begun asking whether humor can be computed—and if so, how.

Any attempt to answer that question immediately runs into a problem: the lack of suitable databases that lend themselves to computational study. For example, a database of similar sentences that are funny and unfunny would allow researchers to tease apart the difference between them and work out how to convert one into the other. But such a database has been sadly lacking.

Enter Robert West at EPFL in Switzerland and Eric Horvitz at Microsoft Research in the US. These guys have used satirical news headlines, which are generally funny, to crowdsource a database of similar sentences that are not funny.

By studying the differences between these sentences, the researchers can see how the switch from funny to unfunny occurs and where the origin of humor must lie. “It would allow us to understand why a satirical text is funny at a finer granularity than previously possible, by identifying the exact words that make the difference between serious and funny,” they say. The result is a unique insight into the nature of humor.

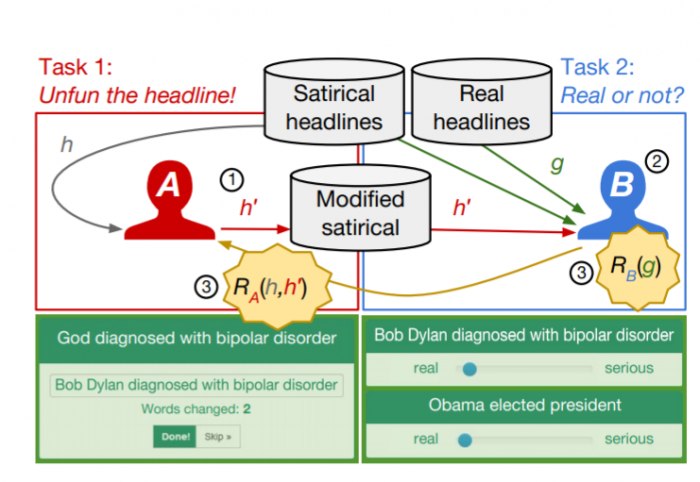

The researchers created the database by building an online game called Unfun.me. Players are given a satirical news headline taken from The Onion and then asked to turn it into a serious news headline by changing as few words as possible. The idea is to fool other players into thinking the headline is real.

For example, in 2001, The Onion published the satirical news headline “God diagnosed with bipolar disorder.” This can be made serious by swapping the word “God” for the name of a real person, as in “Bob Dylan diagnosed with bipolar disorder.” Such a title could conceivably appear on a serious news website. The game then asks players to rank the generated headlines by funniness.

West and Horvitz analyze the resulting database by studying which part of a headline is most commonly changed to make it unfunny. They also look at the nature of the change.

The results make for interesting reading. Headlines are generally made up of several parts: noun phrases, verb phrases, adjective phrases, and prepositions. It turns out that a noun phrase is the part most commonly changed to turn a funny headline unfunny, especially when the word or words come at the end of a sentence.

For example: the satirical headline “Asian economic woes force layoffs of 700,000 pop stars” can easily be made serious by replacing “pop stars” with “workers.”

That points the researchers to a significant conclusion. “Our analysis reveals that the humor tends to reside toward the end of headlines,” they say. They call these phrases at the end of sentences micropunchlines.

But the researchers are able to go further by examining the nature of the change. To help, they turn to a well-known theory of humor published by Victor Raskin in 1985. This suggests that the difference between a funny and an unfunny headline must follow special rules. “The two scripts must be opposed to each other along one of a small number of dimensions,” say West and Horvitz. “One of the two scripts must be possible, the other, impossible; one, normal, the other, abnormal; or one, actual, the other, non-actual.”

In the above example, laying off 700,000 workers is possible or actual, but laying off 700,00 pop stars is impossible and non-actual. In the earlier example, God—being perfect—cannot possibly have bipolar disorder, whereas Bob Dylan, a mere human, could. “Our results thus confirm the theory empirically,” say the researchers.

And they say the same mechanism could also provide insights into rudeness, sexism, euphemisms, and so on by asking people to change sentences by one word.

An interesting question is whether these insights provide a useful way of moving in the opposite direction—making an unfunny sentence funny.

That’s much harder. The team point out that even at The Onion, 600 headlines are considered before only 16 actually make it into print each week. Clearly, it’s much easier to remove humor than to add it.

Perhaps that might change through the insights this paper provides, if they can be computed. With this kind of computational humor, it may be that the internet will soon be inundated with giggle-inducing headlines created by the greatest satirical comic in history—artificial intelligence.

We can’t wait. Ahem.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1901.03253 : Reverse-Engineering Satire, or “Paper on Computational Humor Accepted Despite Making Serious Advances”

Deep Dive

Artificial intelligence

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

What’s next for generative video

OpenAI's Sora has raised the bar for AI moviemaking. Here are four things to bear in mind as we wrap our heads around what's coming.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.