Meet the astronaut trainer getting billionaire space tourists ready for liftoff

A trip to space is no vacation. Getting there requires some serious prep work—even for people whose checkbooks have paid for the golden launch ticket.

SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Virgin Galactic are all promising to send private citizens into space within the next five years. In September, SpaceX announced that its first private paying customer will take a trip around the moon in 2023. Blue Origin founder Jeff Bezos has said he is aiming to send tourists to space by next year. And Virgin Galactic founder Richard Branson recently claimed that his company would send people up before Christmas.

Meanwhile, the Russian Space Agency has already taken multiple paying individuals to space.

It’s seeming increasingly likely that more private citizens will be heading there soon. No wonder so many firms have spotted a potentially lucrative gap in the market: services to help astronauts prepare for launch.

This article also appears in Clocking In, our newsletter covering the impact of emerging technology on the future of work. Sign up here—it’s free!

Vladimir Pletser is a direct beneficiary of the space tourism industry’s growth. He was recently hired as the director of space training operations at startup Blue Abyss, based in the UK. The company is raising money to construct facilities that will offer space training to government astronauts as well as what Pletser prefers to call citizen astronauts. “‘Space tourist’ is a bit pejorative,” he says. “Even a person who would fly privately in space would be trained and become a real astronaut and would have something to do in flight. They would participate in the operation.”

He will train astronauts on things like moving in zero gravity, performing simple experiments, and exercising in space on longer trips. Pletser’s citizen astronauts will dive in pools to practice motion in zero or moon gravity, sit in centrifuges that simulate G-forces, and go on flights that provide a microgravity experience , similar to some of the training government astronauts undergo as well.

There’s a hint of play-acting here: Pletser thinks part of Blue Abyss’s business will come from people footing multimillion-dollar bills who want an advance training “experience.” But astronaut trainers will actually be needed to get even a suborbital traveler up to speed on things like emergency procedures, how to move safely, and how any experiments to be performed will work in microgravity. And Blue Abyss isn’t the only organization already hiring astronaut trainers. The National Aerospace Training and Research Center offers FAA-approved suborbital and advanced space training programs.

So what qualifications do you need to train people for space? For Pletser, it was going through training himself.

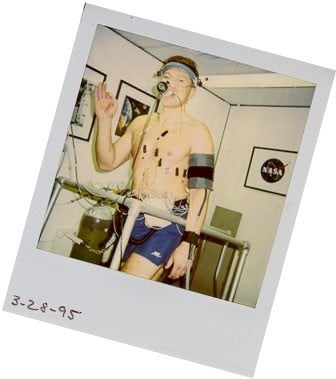

He is no stranger to astronaut training and the competitive astronaut selection process. He was first selected as an astronaut candidate by Belgium in 1991 but was passed over at the end of the European Space Agency’s selection process. He then applied to be a NASA payload specialist in 1992 but, once again, had no luck. In 1995 he made it further than before, when Belgium presented him as a candidate for a Spacelab shuttle mission and he passed medical inspection. After two months of training, though, it happened for a third time: he was told he wouldn’t be on board the space shuttle.

Soon after that disappointment, he decided to take what he had learned from these experiences and work to help prep others for space instead. “I have a bit of both backgrounds—receiving and giving training,” Pletser says. “I understand how to talk to astronauts—NASA, ESA, or Russian cosmonauts—and anticipate what is needed.”

Although he has never reached space, he has spent more than 39 hours weightless. Before coming to Blue Abyss, he had more than 30 years’ experience performing research for the European Space Agency on parabolic flights that simulate microgravity. He has flown more than 7,300 parabolas on 12 airplanes, a Guinness World Record. He is using this experience to design Blue Abyss’s flight training program.

Pletser obviously has had a unique career trajectory. Just as there is no one single route to becoming an astronaut, he believes, there will be multiple paths to becoming a trainer in the future. “[Being an astronaut trainer] might not even be a full-time career,” he says. “People may do that for certain periods of time and then go back to a previous job, possibly in space research.”

Pletser himself doesn’t want to spend the rest of his career just preparing others to go on the trip of a lifetime. “People often ask me: ‘Have you been to space?’” he says. “I always answer: ‘No—not yet.’”

This article is part of a series on jobs of the future. Check out other futuristic job profiles here.

Deep Dive

Space

How to safely watch and photograph the total solar eclipse

The solar eclipse this Monday, April 8, will be visible to millions. Here’s how to make the most of your experience.

How scientists are using quantum squeezing to push the limits of their sensors

Fuzziness may rule the quantum realm, but it can be manipulated to our advantage.

The great commercial takeover of low Earth orbit

Axiom Space and other companies are betting they can build private structures to replace the International Space Station.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.