Specialized chips are threatening to take over cryptocurrencies, and they look unstoppable

If cryptocurrencies’ greatest common asset is their decentralized nature—the inability of any one person, corporation, or united group to control a coin’s future—then there’s no existential threat quite like the rise of crypto-mining ASICs.

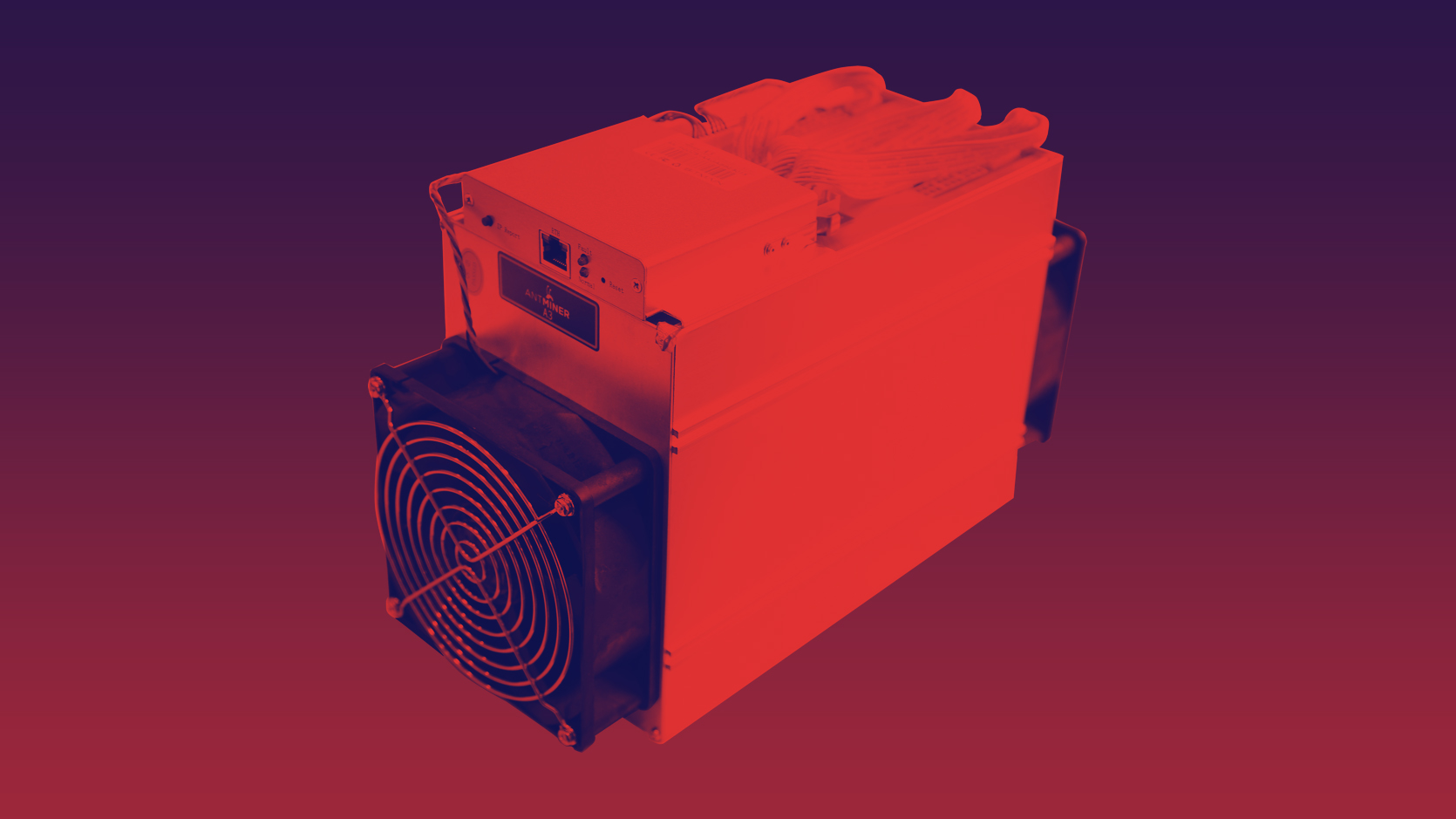

Application-specific integrated circuits are chips specially designed to perform the kinds of computations needed to mine a chosen currency more efficiently than general-purpose hardware can. That miners can use ASICs to gain an advantage probably wouldn’t represent such a threat if one company, the Chinese firm Bitmain, hadn’t come to dominate the market. Now David Vorick, the founder of the three-year-old blockchain-based file storage service Sia, and his team are going head-to-head with Bitmain, the mining industry’s Goliath.

This piece first appeared in our twice-weekly newsletter, Chain Letter, which covers the world of blockchain and cryptocurrencies. Sign up here—it’s free!

Vorick’s ASIC manufacturing company, called Obelisk, is an attempt to make an end run around Bitmain’s relentless production of new ASICs. But it also responds to a larger urge in the cryptocurrency community to keep coins “ASIC resistant” by tweaking their software. The hope is that such tinkering will beat back big mining players like Bitmain. But Vorick says it’s a fool’s errand, and he speaks from personal experience.

Bitmain actually beat Obelisk to market with an ASIC tailored to mine Siacoin, though the new startup plans to ship its first-generation miners in about eight weeks. Vorick says the ordeal has convinced him that ASICs aren’t going away anytime soon. Because hardware makers have so much design flexibility, he says, there will “always be a path” to developing customized chips that can work around new mining algorithms meant to resist them.

Cryptocurrency mining is the process of adding sets, or “blocks,” of new transactions to the blockchain. Miners use large amounts of computing power to guess a specific number that cryptographically links the new block to the preceding one—the key to making the record tamper-proof. By finding the number, a miner proves that it did the work required to secure the chain, and reaps a cryptocurrency reward.

Just a few years after Bitcoin emerged, startups began racing to build ASICs for mining the currency. Nearly all of those companies have gone belly-up, however—except Bitmain. The company is estimated to control more than 70 percent of the market for Bitcoin-mining hardware. It also uses its hardware to mine bitcoins for itself. A lot of bitcoins: according to Blockchain.info, Bitmain-affiliated mining pools make up more than 40 percent of the computing power available for Bitcoin mining.

And Bitmain has been branching out of late, releasing new ASICs designed to mine Ether, Zcash, and Monero in addition to Siacoin. That’s prompted concern among the users and developers of these coins that Bitmain and its affiliates could gain a majority of their networks’ mining capacity, which would give it enough power to disrupt or maliciously attack the networks. And it’s inspired calls for software upgrades (which, in Monero’s case, the developers have delivered) in the name of ASIC resistance.

If Vorick is right, though, that may be a lost cause—an argument he laid out in a lengthy blog post published this week about his experience with Obelisk. He says he hopes the post will “get people to accept the fact that heavy miner centralization is going to be around for a while.” The next question, says Vorick, is: “What can we do with our protocols and our designs and our communities to make sure this isn’t a catastrophic thing?”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.