The Stabilizer

Spend enough time at MIT, and you start telling people’s life stories by the numbers. Aside from the occasional hiatus in Washington, DC, including a stint as secretary of the Air Force in the 1990s, Sheila Widnall has been at the Institute for 62 years. She’s earned three degrees, all in Course 16, and three patents, all shared with former students whose research on windsails, turbines, and airfoils she shepherded. She’s been an Institute Professor for 20 years and has published scores of research papers, dealing with everything from aeroelasticity to helicopter noise. But her most lasting scientific legacy consists of one shifting shape.

“If you’re in science and engineering, and you do something really well, they name it after you,” says fellow aero-astro professor Ed Greitzer. Just as forces are named for physicists and species for biologists, instabilities—descriptions of how specific gases, liquids, or plasmas behave—are named for the fluid dynamicists who discover them.

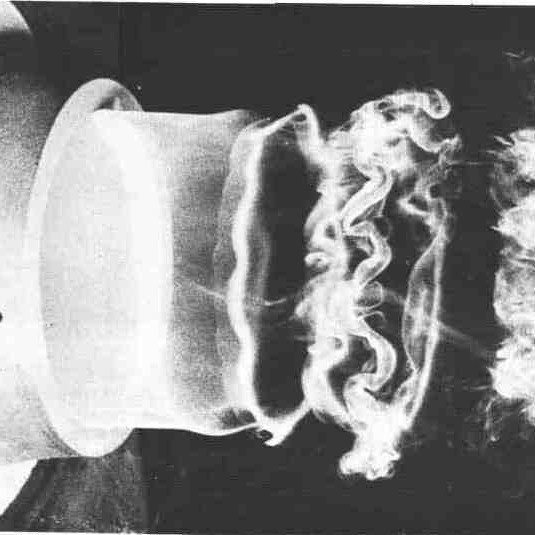

The Widnall instability, which she described in a series of papers in the early 1970s, applies to vortex rings: if you’ve ever watched a smoke ring slowly widen and pull apart, you’ve seen it. It also characterizes the turbulent wakes that aircraft leave behind. “Aircraft trailing vortices have little waves that are generated and then break up,” she explains. “If another aircraft intercepts that trailing vortex, someone can be killed, because it’s a swirling flow.” For example, if one plane lands and a second follows too closely on its heels, it might hit the wake, tip over, and crash. A proper understanding of the Widnall instability helps prevent such accidents (like one that took the life of an Air Force friend of Widnall’s) as well as overcorrections (“The first time they landed the 747 in Italy, they shut down the airport for an hour,” she says). The experts who develop landing standards used the Widnall instability to arrive at a rule of thumb involving yet another number: “People now know that if you land airplanes three minutes apart, that’s going to be safer,” she says.

“It was the only job I would have taken in DC. I wanted to be with the people in the Air Force. I wanted to fly.”

Widnall’s CV includes a long string of firsts. When she was made an assistant professor of aeronautics and astronautics upon earning her PhD at MIT in 1964, she became the first woman to earn a faculty position in the School of Engineering. She was also the first woman to serve as MIT’s chair of the faculty—an office she held from 1979 to 1981—and the first female president of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. In 1993, she became the first woman to lead a branch of the American military when President Bill Clinton tapped her for the top Air Force job.

Widnall was born in 1938 in Tacoma, Washington, and grew up near the final approach to McChord Air Force Base, in the shadow of planes coming and going. (“I spent my childhood waving at pilots,” she told MIT News in 2004, when she was elected to the National Women’s Hall of Fame. “Now they wave at me.”) When the Clinton administration called initially to see if she’d consider a job in Washington, she said no; she had no interest in working for NASA or at the upper levels of the Department of Defense. But the opportunity to lead the Air Force was an offer she couldn’t refuse. “It was really a kick,” she says. “It was the only job I would have taken in DC. I wanted to be with the people in the Air Force. I wanted to fly.” While leading the Air Force, she picked up another defining number: “I went supersonic! And I pulled nine Gs.”

There are other important firsts, too. She is often the first to arrive at the department in the morning. “When I get calls at 7 a.m., I don’t have to look at the caller ID to know who it is,” says Greitzer, who served as the associate head and then deputy head of aero-astro for nearly a decade.

Those early-morning calls often come because Widnall has solved a difficult problem they were both interested in—“usually in a way that I would never have thought about, because it’s a carom off this thing to ricochet off that thing,” he says. “She’s sort of a force of nature.” Sometimes, he adds, she tells him that he is the one who must do the caroming. “And there’s usually nothing I can say,” he says. “Everything she says I should do, I think, ‘Oh, yes … I should.’”

And it’s likely she was the first undergraduate advisor to take her charges on an indoor skydiving trip in a vertical wind tunnel. “While I was hoping to see her get into the wind tunnel, she did not do it,” recalls one of her former advisees, John Graham ’17, SM ’17. “But I’m sure if she were younger she would have hopped in, no doubt.”

The Widnall report

When Widnall was 17, her uncle, who worked for a mining company, gave her a chunk of uranium. She made it the center of a project that took first prize at her local science fair in Tacoma. Her win drew the attention of one of the fair’s judges, who happened to be an MIT graduate. He suggested she go there too, and offered to secure her a scholarship. “I said, ‘Okay, where’s that?’” she recalls. But she took his advice. Going to MIT would shape the course of her life—and her presence at the Institute would help to reshape MIT as well.

“If engineering doesn’t make welcome space for [women] then engineering will become marginalized.”

“It’s a little hard to remember how it all got started,” she says, “[but] the contributions that I’ve made to MIT in some of these policy areas have been quite substantial.” Widnall retrieves a thick booklet from a desk drawer and plunks it onto a table: “This is typical.” It’s a copy of In the Public Interest, a report generated by a faculty committee that she chaired in 2002, which deals with restrictions on research imposed by the federal government after the September 11 attacks. “They didn’t want our international students to be able to take courses,” she explains. “And we said, ‘We’re a university. We’re completely open.’” The report’s conclusions—that classified research should not be carried out on campus, and that no student should be required to have a security clearance to perform research, read documents, or take advantage of MIT’s facilities—articulated policies that are still in place today.

Over the years, Widnall has also chaired committees on academic responsibility, undergraduate admissions and financial aid, discipline, and educational policy. (She found time to serve on MIT Technology Review’s board of directors from 2009 to 2014 as well.) Her committee’s report on departmental reorganization—inspired by the sudden dissolution of the Department of Applied Biological Sciences in 1988, which shocked faculty and students, and which she calls “a total outrage”—outlined a formal process for reorganizing or dissolving departments that guarantees faculty jobs. Now, whenever such a change occurs, the resulting brief is called a Widnall report. Within the aero-astro department, “she’s part of our conscience, almost,” says Greitzer, who currently works with Widnall on the department’s two-person faculty awards and recognition committee. “She holds us to high standards.”

Her work of this type has extended outside of MIT. As secretary of the Air Force, she distilled the service’s implicit philosophy into a set of core values that is still in use today: “Integrity first,” “Service before self,” and “Excellence in all we do.” (If you attend any presentation by an Air Force officer, you’ll see the core values at the bottom of the opening presentation slide, Widnall says. “And the [officer] has absolutely no idea where they came from. They’re just the Air Force.”) “I did other things—launch vehicle programs and fighter planes, the standard stuff that Air Force secretaries do,” she says. “But above that was the core values.”

In 2003, she was a member of the investigative board that sought to figure out why the space shuttle Columbia had disintegrated as it returned to Earth earlier that year. They found that although the direct physical cause may have been a loose piece of foam that struck a vulnerable part of the left wing, cultural and organizational issues also played a role. The board issued a number of recommendations to help NASA avoid future accidents, from improving imaging systems to establishing an independent standards-setting group, now called the Technical Authority.

One chart from the investigation, detailing the spread of debris across a wide swath of the American Southwest, hangs on the wall of Widnall’s office, just inside the door. In order to teach students about the many dimensions of the problem, “I wanted a copy to bring up here,” she says. “[NASA was] so embarrassed that they had had a crash, they wouldn’t give it to me. And I just fought them back, and insisted.” In other words, she became part of their conscience too, whether they liked it or not.

The Widnall effect

As Widnall reflects on her time at the Institute, it becomes clear that she’s witnessed—and helped push along—its ongoing transformation from a primarily male institution to one that’s more welcoming to women and more diverse overall. When she first got to MIT, in the fall of 1956, she was surprised by two things: the architecture of the women’s dorm on Bay State Road (“It never occurred to me that houses could have windows on only two sides,” as she once put it), and the paltry number of women (23) in her class. (At the time, there were 129 female students at the entire Institute, out of 6,000 total.) As she progressed from undergraduate to graduate student to professor, the proportion of women kept shrinking. In one aero-astro faculty photograph, from 1967, she is the only one without a tie.

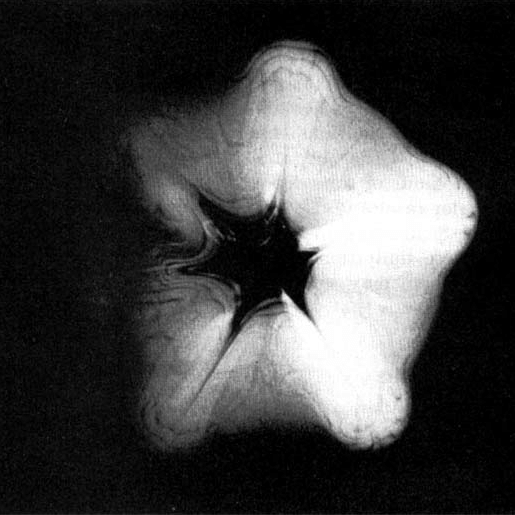

Smoke patterns show the instability of a round jet (left) and the growth of waves around a vortex ring (right).

“Trailing vortices are created by aircraft when they fly. Those vortices have an instability that causes them to break up. The short-wave instability is called the Widnall instability. It’s also something you see in vortex rings. It’s just a really fundamental fluid mechanics instability. When I was secretary of the Air Force, I went up to Princeton to give a seminar. Some of the faculty were talking about the Widnall instability, and my Air Force assistant thought they were insulting me. I thought he was going to punch someone. And I said, ‘No, it’s a compliment!’ It’s a real honor in fluid mechanics to have an instability named after you.”

But as fluid dynamicists well know, nothing is ever completely stable, and sometimes a properly applied force can help speed things along. “Increasing the percentage of women undergraduates—that was one of my big things,” Widnall says. She quickly identified a number of places where women tended to leave the pipeline. One major problem was in the admissions process itself. In the late 1980s, Widnall encouraged Arthur Smith, who would soon become dean for undergraduate education, to revamp MIT’s admissions process. He’d shared with her data from his study of the relationship between students’ math SAT scores and their actual performance once they arrived at MIT—and his conclusion that the test was a bad predictor of success for women. At her urging, he rethought MIT’s use of the test, and from 1989 to 1990 the proportion of women in the freshman class grew from 26 percent to 38 percent. “We talked a lot about wanting more women students,” Widnall says. “And I said, Look: the women we want are the women that are applying. We should just admit more of them.”

Meanwhile, as more and more women arrived at MIT, Widnall worked to make sure they felt welcome and confident. One freshman seminar she originated—in 1974, with fellow pioneering faculty member Millie Dresselhaus—interspersed job talks with drafting and welding practice. Called “What Is Engineering?,” it was meant to demonstrate what a career in the field could look like, aimed at students who might not have grown up realizing they could pursue one. For some young women, Widnall’s very presence helps make this goal seem achievable. “It was so important to me that she was a strong woman in aerospace,” says aero-astro major Annika Rollock ’18, who requested Widnall as her advisor. “I never had really gotten a chance to see a strong female figure in the field that I wanted to go into.”

Widnall has also used her platform to explain the problem to

others outside MIT. In 1988 she called the lecture she gave as president of AAAS “Voices from the Pipeline,” and walked through the results of a demographic study to spell out why women might abandon engineering during or after graduate school. Twelve years later, she gave a speech to an audience full of engineers in which she listed dozens of things that might still be preventing women from succeeding. These ranged from the systemic—a lack of role models; professors who default to masculine pronouns—to the seemingly trivial, like the expectation that all engineers will have a large slice of pi memorized. (This, she said in the speech, seemed to her “like a guy sort of thing” and had gotten her thinking about other expectations that, though superficial, “nevertheless operate to keep women out of engineering.”) Addressing these roadblocks, she explained, was as important for the field as it was for those who were kept out of it. “Women are going to be a huge force in the solution of human problems,” she said. “If engineering doesn’t make welcome space for them … then engineering will become marginalized.”

Many of these points still ring frustratingly true. (Widnall is cochairing a National Academies task force on how sexual harassment in the academic environment affects the careers of women in science; it will release its report in June. As Air Force secretary, she had co-chaired a similar task force for the Department of Defense back in 1994-95.) But things have certainly shifted. At this point, 46 percent of MIT’s undergraduate engineers are women, she says. Nationwide, the percentage hovers around 20. “So MIT is doing over twice as well,” she says. “I think we’ve come a very long way.”

These days, in addition to teaching, advising a dozen undergraduates, and helping her students launch their own careers, Widnall is also head of an external advisory committee for United Launch Alliance, a joint venture of Boeing and Lockheed that’s partnering with Jeff Bezos’s private aerospace company Blue Origin. As Blue Origin works to develop technologies to lower the cost of spaceflight and make it accessible to individuals and businesses, her committee is helping the company select rocket engines. “There’s a reason they call it rocket science,” she says. “There are so many things that can go wrong when you’re building a rocket engine, you have to have a really carefully thought-out test program.” But at age 79, she’s thinking about retiring sometime soon: “I’m getting to the point where I really should.”

As she contemplates scaling back her work at MIT, another family member may be arriving on campus in the fall. Widnall and her husband, engineer Bill Widnall ’59, SM ’62, ScD ’67, who developed guidance and control systems for the Apollo program, have two children and two grandchildren, one of whom was just admitted to MIT. (“He’s obviously delighted,” she says. “We’ll see how that works out.”) But no matter when she retires or where her grandson enrolls, she has high expectations for the institution she calls home. “I think that MIT should be the best university in the United States,” she says. “If you ask ‘What universities are contributing the most to our society?’… I want MIT to be that university.”

She pauses briefly. “It’s not an unreasonable expectation that that would be us.” As usual, she’s probably right. After all, when people expect things of you, you often find that you can do them. Call it the Widnall effect.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.