The Risky Business of Stress

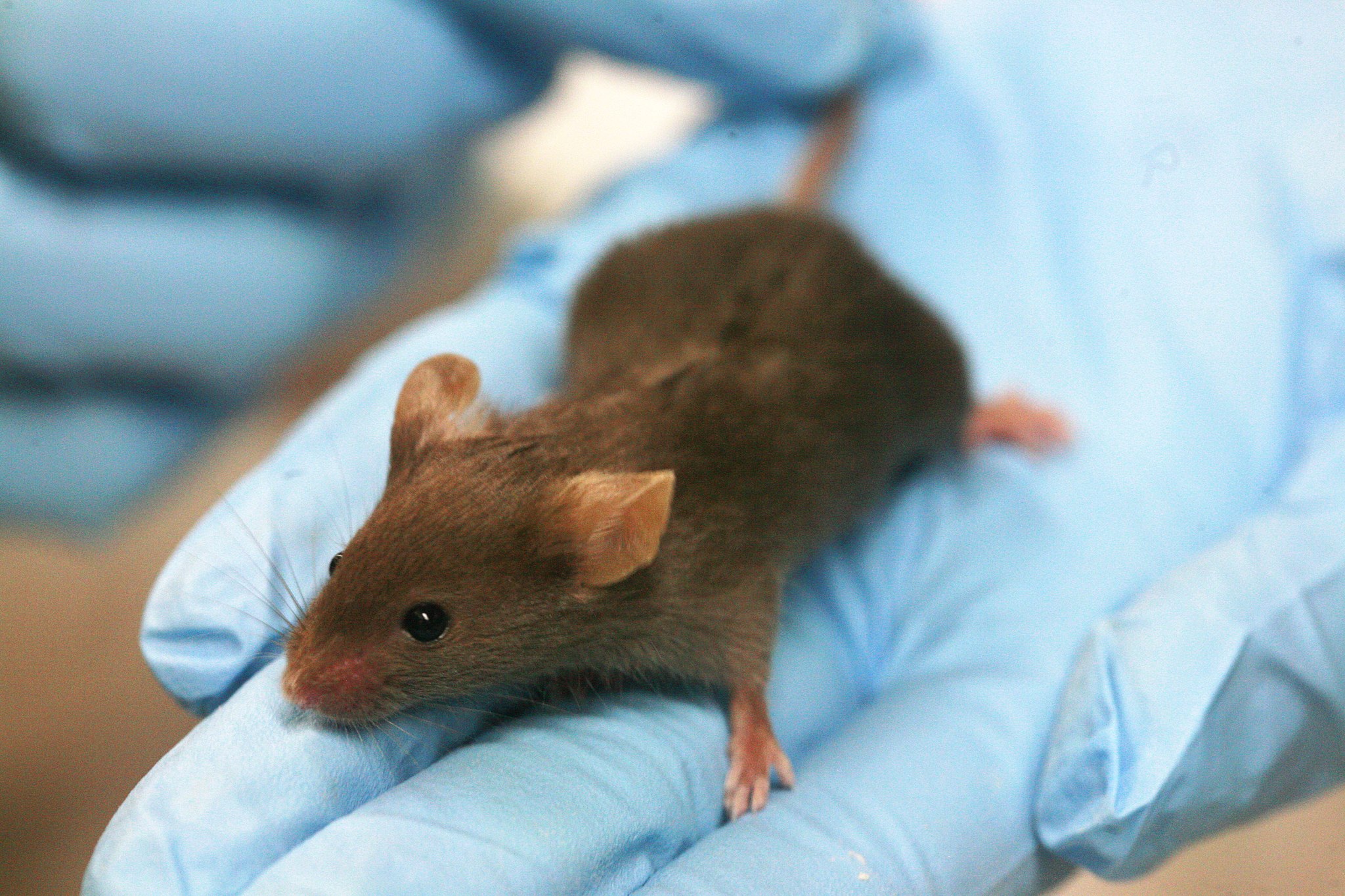

It’s not easy to choose between two options that have both positive and negative elements, such as a job with a high salary but long hours and a lower-paying job that allows for more leisure time. MIT neuroscientists have now discovered that making decisions in this type of situation, known as a cost-benefit conflict, is dramatically affected by chronic stress. In a study of mice and rats, they found that stressed animals were far likelier to choose high-risk, high-payoff options.

The researchers also found that impairments of a specific brain circuit underlie this abnormal decision-making, and they showed that they could restore normal behavior by manipulating this circuit. If the circuit could be tuned in humans, it could help patients with disorders such as depression, addiction, and anxiety, which often feature poor decision-making.

MIT Institute Professor Ann Graybiel, PhD ’71, first identified this brain circuit in 2015 and showed that disrupting it using optogenetics, a technique that allows neurons to be controlled with light, could steer animals toward choosing higher-risk options.

In the new study, published in Cell, Graybiel and colleagues trained normal rats and mice to choose between a maze arm that exposed them to bright light (high-risk) and led to a reward of full-strength chocolate milk (high-payoff) or one involving dimmer light (low-risk) and weaker chocolate milk (low-payoff). The animals started out choosing each side about half the time, but as the researchers gradually increased the concentration of the chocolate milk found in the dimmer side, they began choosing that side more frequently.

When animals that had been exposed to a short period of stress every day for two weeks were put in the same situation, however, they continued to choose the bright light/better milk side even as the chocolate concentration increased on the dimmer side. The researchers believe that when animals are chronically stressed, circuit dynamics shift and a set of neurons involved in this type of decision-making becomes overexcited.

“Somehow this prior exposure to chronic stress controls the integration of good and bad,” Graybiel says. “It’s as though the animals had lost their ability to balance excitation and inhibition in order to settle on reasonable behavior.”

Once this shift occurs, it remains in effect for months, the researchers found. However, they were able to restore normal decision-making in the stressed mice by optogenetically manipulating a set of neurons in the circuit. This suggests that the circuit could be susceptible to manipulation that would restore normal behavior in human patients.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.