Strava’s privacy PR nightmare shows why you can’t trust social fitness apps to protect your data

For years, I used the popular activity-tracking app Strava to log my bike rides, almost all of which started and ended at my San Francisco apartment. At some point I thought, hey, maybe it’s not a great idea to share such precise data about my location, so I set up an online perimeter several blocks in diameter around my home to make the beginning and end of my journey a little less obvious. That way, the app wouldn’t show my movements once I’d entered that zone.

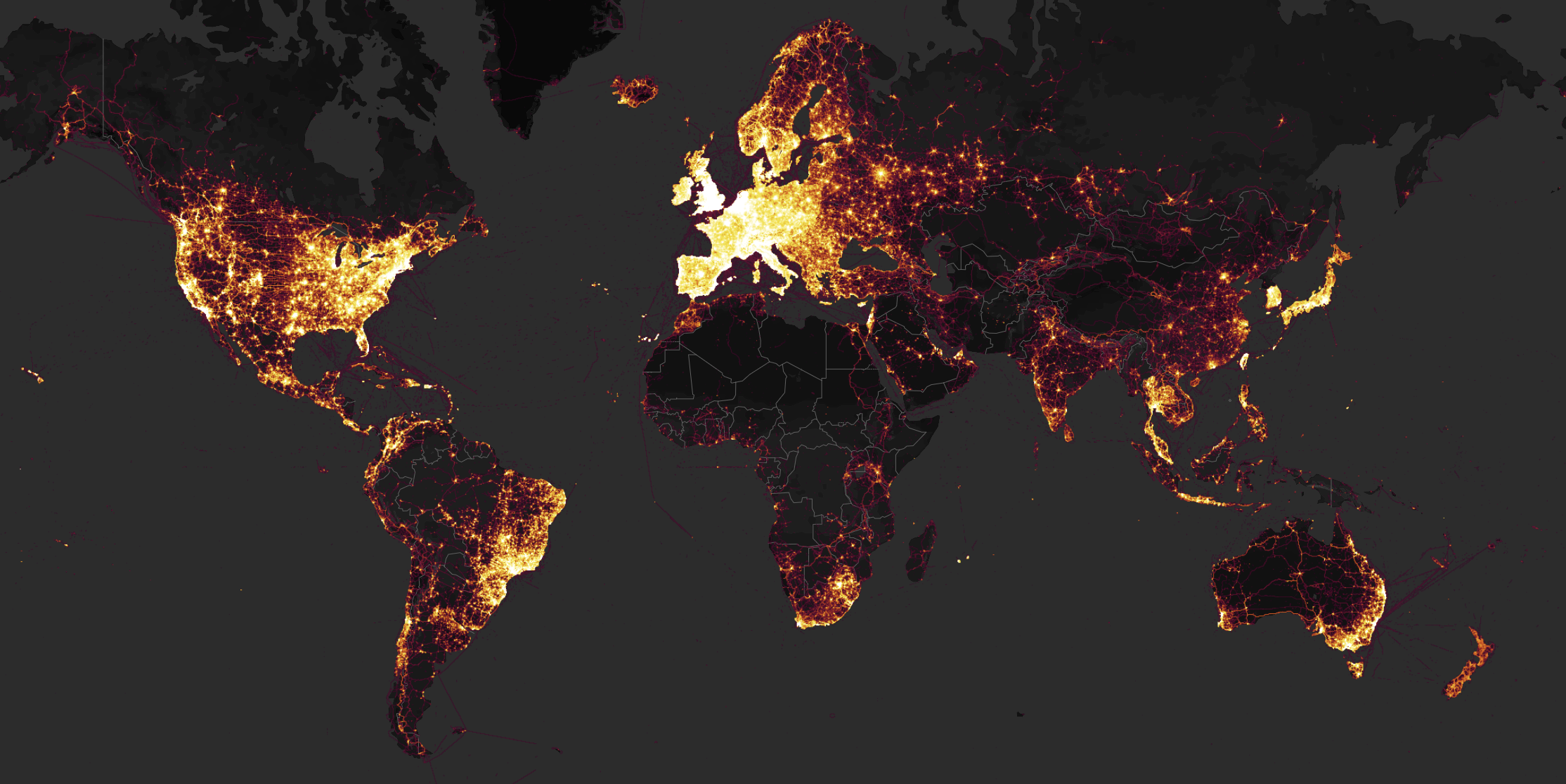

Millions of Strava’s other users clearly aren’t as wary. Late last year, the company released a searchable heat map based on a billion activities logged publicly by people who use the app either just on a smartphone or along with an activity tracker like a Fitbit. Researchers have now shown that the data can be used to reveal the location of sensitive sites like US military bases in countries such as Afghanistan and Syria, as well as the exercise routines of their occupants. Chances are that most of the people using Strava in these places are soldiers and other military personnel, so it stands to reason that the handful of little bright areas on otherwise dark portions of a map show where they’re hanging out and moving around. Strava did not return a request for comment.

This is a security risk for the military, which in response is apparently updating its rules about how gadgets are used at its sites. For the rest of us, it’s an important reminder that tech companies that urge you to track aspects of your life and share them with other people really don’t want you to keep those tidbits private. Many, like Strava, Facebook, and Twitter, have made sharing a cornerstone of their business models. For the foreseeable future, you’ll need to figure out for yourself what to keep private and what is safe to share—which is often quite difficult to determine, much less act upon.

Strava needs its users to share their rides, runs, and swims. After all, the more activities they share—currently users post over 1.3 million activities per day—the more evidence Strava has to encourage others to keep using the app, and perhaps even trade up from the free version to an $8-per-month one. More shared data also means more to feed into Strava’s Metro business, which sells anonymized commuter data to cities. The company wasn’t profitable as of this past fall, but its CEO, James Quarles, clearly sees these two lines of business as the main paths to growth, assuming it gets more and more information from its users.

And, frankly, using Strava in a very social way can be addicting. Since it began, in 2009, the company has perfected the art of fitness gamification and competitive sharing. Its app lets you see basic stats from your and your friends’ workouts; it encourages you to give each other kudos for completing activities; it gives awards for things like getting your best time on a specific segment of a bike ride or completing it faster than other riders. You can drill down on specific bits of a ride or run to see how you or others stack up. And this is all stuff you can do without even paying for the app—the premium version gives you access to additional features like a “suffer score” that analyzes your heart rate.

You might not want to share everything you’re doing on Strava, though. This isn’t only a matter of personal privacy. As Beau Woods, cyber safety innovation fellow at the Atlantic Council, points out, there are significant implications when it comes to sharing collective data, especially if a person or group of people traces the same path over and over. The military has just had a big wake-up call about this risk.

Doing something about this isn’t that easy. While Strava includes tons of straightforward ways to look at the data its community has collected, it’s actually rather difficult to find, understand, and use its privacy settings. For instance, in Strava’s iOS app you can tap the “More” tab at the bottom right of the app, then tap “Settings,” and then “Privacy,” to find a bunch of sliders. (You can also get there by tapping the “Feed” tab and then hitting “You” to see a prompt to go to your privacy settings.) Prominently placed at the top of the privacy settings page is an “Enhanced Privacy” option. This is turned off by default, and when it’s off it means anyone can see your Strava profile and photos. Other Strava users who are logged in can follow you and, perhaps most important, view and download any activities you log with the app.

That’s not to say that turning on “Enhanced Privacy,” as I’ve done, means you are hidden on the site. Your activities won’t show up on your profile page, but you’ll still need to mark them as private to ensure they don’t show up in other parts of Strava’s data-rich universe—for example, in the leaderboards that are connected to run and ride segments. To make activities private by default, you’ll have to use that slider (and it will only make new activities private by default). You can’t set up a perimeter around your home base to cloak it unless you go onto Strava’s website, which is a pain if, like many of us, you’re mostly using the service on your phone.

Part of the reason I share on fitness apps is that it feels good to let people know I got out there and had fun (and suffered!) doing something good for my body and my mind. And it feels good to get the kudos, especially from friends with much more impressive levels of fitness. Yet there’s a very real cost to this sharing, so it’s vital that we take the time to slog through our apps and figure out what we’re getting and what we’re giving up, and then adjust how we use them (and how they use us) accordingly.

Which reminds me—since I recently moved, I need to go onto Strava’s website and create a new safety perimeter before I head out on my next ride.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.