How Tweets Translate into Votes

The role of Twitter in politics has never been more prominent. President Obama, sometimes called the first social-media president, clearly outperformed his rivals in terms of popularity and output. President Trump also uses Twitter, albeit more controversially, to drive debate, air grievances, and set policy.

Clearly, social media plays a major role in political discourse. Many politicians send hundreds or thousands of messages during election campaigns and invest considerable resources into their social-media presence.

And that raises an interesting question. Does this effort translate into votes?

Today we get an answer of sorts thanks to the work of Jonathan Bright and pals at the Oxford Internet Institute in the U.K. These guys say that the two recent elections in close succession in the U.K. provide a unique opportunity to test the role Twitter played in the outcome.

Most research into the electoral effect of social media has focused on single elections. That can lead to problems because it is hard to separate the effect of social media from other factors, such as the level of professionalism demonstrated in the campaign, the amount of campaign funds involved, and so on.

Comparing elections that are far apart is also tricky, because the way politicians and voters use social media can change dramatically over electoral time scales, usually in the region of five years or so.

So the U.K.’s two recent elections offer a unique opportunity to look deeper. The first election that Bright and co studied was on May 7, 2015; the second was on June 8, 2017, after a snap call that gave candidates just 24 days to prepare.

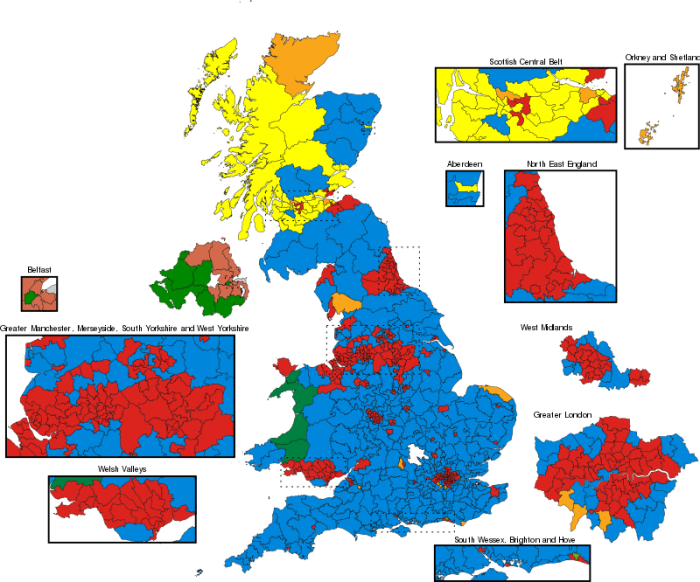

In these elections, the British public elected 650 members of Parliament, each representing a district of about 70,000 voters. About seven major political parties competed, together fielding a total of 6,000 candidates. Of these, 822 politicians campaigned in both elections and so were counted twice.

Seventy-six percent of the 2015 candidates used Twitter, compared with 63 percent in 2017. The drop is probably the result of the rushed nature of the 2017 election. Many candidates were chosen at the last minute, giving them less time to organize a social-media strategy.

Nevertheless, Twitter activity increased in 2017. Candidates with a Twitter account sent a median of 86 tweets in 2015—that’s 3.6 a day. This number rose to 123.5 tweets in 2017—just over 5.1 a day.

These numbers hide a significant difference between the Twitter presence of incumbent politicians and challengers. In 2015, 87 percent of incumbent politicians had Twitter accounts, compared with only 73 percent of challengers.

In 2017, the difference was even bigger. In this case, 84 percent of incumbents had accounts, compared with only 58 percent of challengers. Again, the difference is probably due to the hurried nature of the 2017 election.

Bright and co set out to answer a simple question: do politicians who make greater use of Twitter gain a higher percentage of the vote?

Their conclusion: politicians with Twitter accounts do get a higher share, though not by much.

Although the overall impact of Twitter is small, some groups do better than others. “MPs that had a Twitter account typically had vote shares around 7- 9% higher than those who did not,” say Bright and co.

And they calculate that politicians can claim an extra 1 percent share of the vote by increasing the number of tweets they send out by a factor of between 0.28 and 1.75.

That might look like a small increase, but in many districts it would have been decisive. “Around 14% of the electoral competitions which form the basis of our study were won by a margin of less than 5 percentage points, and 4 percent of them were won by a margin of less than 1 percentage point,” say Bright and co.

That will be food for thought for commentators who have downplayed the importance of social media. Some argue that messages spread this way reach only loyal voters and do little to convert other voters. This work appears to discredit that idea.

As Bright and co put it: “Overall the evidence suggests social media use makes a genuinely important difference to electoral campaigns.”

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1710.07087 : Does Campaigning on Social Media Make a Difference? Evidence from Candidate Use of Twitter During the 2015 and 2017 UK Elections

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.