Prosthetics You Can Feel

A new surgical technique devised by MIT researchers could allow prosthetic limbs to work much more like natural limbs. With the help of muscle grafts and feedback from existing nerves, amputees would be able to sense where their prosthetics are in space and feel how much force is being applied to them.

This type of system could help reduce the rate at which patients decide to reject their prosthetic limbs, which is around 20 percent.

“We’re talking about a dramatic improvement in patient care,” says Hugh Herr, SM ’93, a professor of media arts and sciences and the senior author of the study. He adds that until now, there’s been no robust neural method for a person using a prosthesis after limb amputation to sense where the prosthetic limb is in space, or to feel forces applied to it.

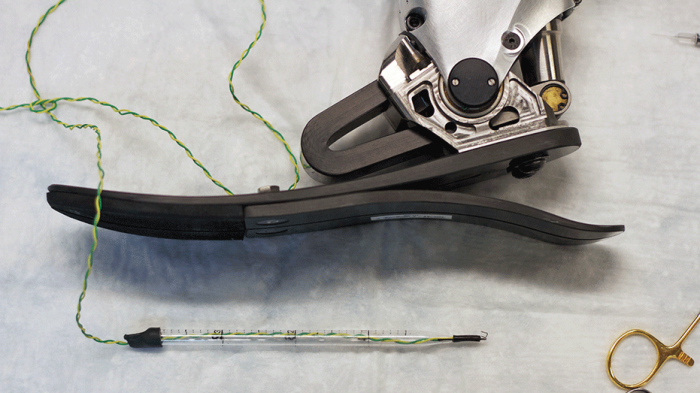

In the new study, which appeared in Science Robotics, the researchers demonstrated in rats that their technique generates sensory feedback from muscles and tendons to the nervous system, which should be able to convey information about a prosthetic limb’s placement and the forces applied to it. They now plan to begin implementing this approach in human amputees, including Herr, whose legs were amputated below the knee when he was 17.

The surgery aims to restore some of the physical basis for proprioception, the body’s sense of its own position and movement. Most muscles that control limb movement occur in what are known as agonist-antagonist pairs: one muscle stretches when the other contracts, and both send sensory information back to the brain. Without these muscle pairs, which are severed in a conventional amputation, people who use artificial limbs have no way of sensing where those limbs are.

“They have to visually follow their hands or their limbs, because there isn’t any feedback from the device or residual limb that tells their brain where their prosthetic limbs are in space,” says Shriya Srinivasan, a graduate student in the Harvard-MIT Program in Health Sciences and Technology (HST) and the paper’s lead author.

Even after the muscles are severed, however, the nerves that sent signals to the amputated limb remain intact in many amputees. Those surviving nerves are the key to the new system: they can be connected to muscle pairs grafted from another part of the body and to a control system Herr’s lab is now developing, which includes a microprocessor that will translate nerve signals into instructions for moving the prosthetic limb.

When the brain sends signals instructing a limb to move, one of the grafted muscles will contract and its agonist will extend, providing neural feedback that allows the patient to feel where the limb is in space.

“Using this framework, the patient will not have to think about how to control their artificial limb,” Herr says. “When a patient imagines moving their phantom limb, signals will be sent through nerves to the surgically constructed muscle pairs. Implanted muscle electrodes will then sense these signals for the control of synthetic motors in the external prosthesis.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.