The Desktop of the Future Is Coming

I’ve got an embarrassingly large number of Post-it notes dotting my desk at work. And at any given moment I have too many tabs open on my Web browser while my computer has several applications running. The augmented-reality startup Meta promises I’ll manage all of that in midair in the not-so-distant future.

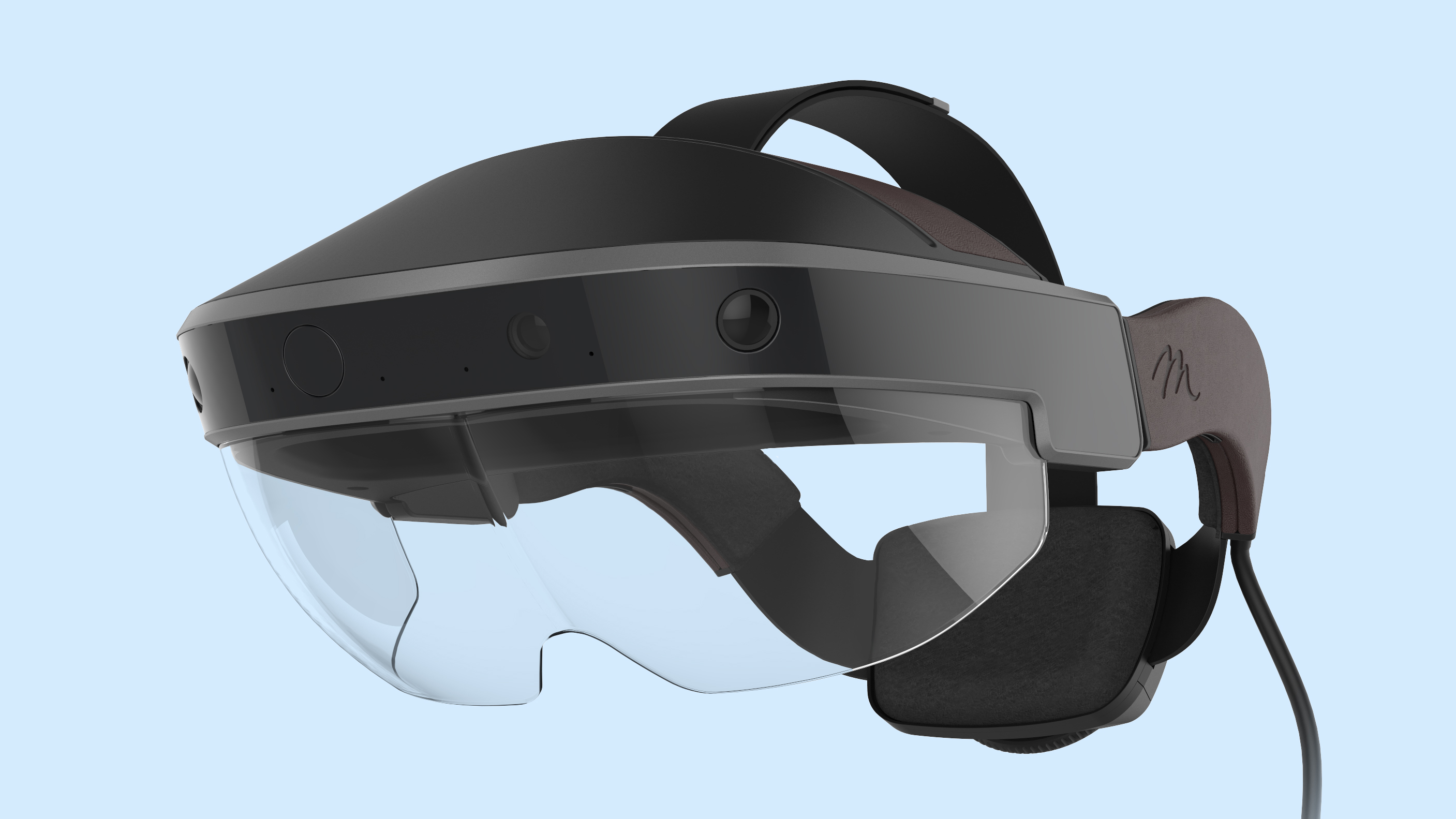

Meta’s new software, Workspace, uses a series of shelves with icons as its desktop metaphor; you’re meant to open applications by grabbing them from a shelf with your hand. The software, unveiled last week, works with the company’s $949 Meta 2 headset, which is currently shipping to some early developers and is planned to be generally available this summer.

Workspace is intended to let you do things like use a bunch of virtual displays at once, resizing by squishing or stretching them with your hands, and moving them at will. You can do likewise with a virtual Web browser, and scroll Web pages with a finger flick.

Workspace works with your smartphone, too: an app Meta developed lets you pull hand-drawn notes off your phone and place them anywhere you want in the air in front of you, and you can do the same with pictures and videos, too, making it possible to surround your real desk with a virtual array of reminders and cute baby photos.

Meron Gribetz, Meta’s founder and CEO (and one of MIT Technology Review’s 35 innovators under 35 in 2016), has spoken about his plan to rid the startup’s office of computer monitors, and last year said the company would make the change by this past March (see “Workers at This Startup Will Soon Swap Their PC Monitors for Augmented Reality Glasses”).

Meta hasn’t yet gotten there completely, but Workspace, in theory, could make this possible. Ryan Pamplin, a Meta vice president and evangelist for the headset, says almost everyone is using Meta 2 and Workspace daily in the company’s office now—some all day, others just occasionally.

“We are literally doing this for better or for worse, every day. So all my e-mails are written in this. My calendar, it’s all done in this. Even video editing internally is being done inside of this,” he says.

I placed a Meta 2 on my head to try it for myself. A virtual bookshelf appeared in front of me with icons denoting different demos and apps I could open, close, and use with my hands.

First, I grabbed an eye, which opened up a photorealistic human eye that I could stretch and rotate with my hands—an example, I guess, of the potential for manipulating 3-D models. More useful to my line of work was a Web browser, which I opened with hand gestures but then used by typing on a connected keyboard.

It was trickier to do all this than what I’ve experienced with Meta demos in the past. I had to hold my open palm over whatever icon I wanted to grab, wait until I saw circle atop my hand, then close my fist and pull it toward me. This didn’t always work, and I also had trouble moving and adjusting virtual objects and the virtual browser window. Scrolling on a website with a flick of my finger sounded intuitive and simple, but that was tricky, too.

Probably the coolest feature was the ability to doodle a simple sticky note on a smartphone and pull it into the space in front of me. This was easy to do, and when I was done with one I could shove it back onto the phone to get it out of my virtual space.

The fact remains, though, that Meta’s headset is still tethered to a PC, and it’s a heck of a lot heavier and bulkier than the pair of glasses I wear every day. At this point, I can’t imagine wearing it for hours, or even more than an hour, at a time.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.