A Cheap, Simple Way to Make Anything a Touch Pad

How would you like a toy, steering wheel, wall, or electric guitar with a touch pad?

You probably encounter small touch screens every day—on phones and at store checkout counters, for instance—but chances are you don’t come across many touch-sensitive surfaces that are huge or aren’t completely flat. That’s because it’s expensive and tricky to add this kind of interaction to large and irregular surfaces.

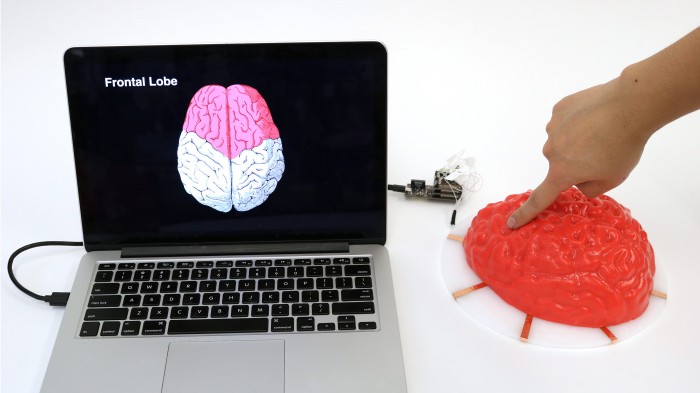

That could change soon, as researchers at Carnegie Mellon University say they’ve come up with a way to make many kinds of devices responsive to touch just by spraying them with conductive paint, adding electrodes, and computing where you press on them.

“These previously static, non-interactive toys and objects can be interactive,” says Yang Zhang, a graduate student who led the project.

Called Electrick, it can be used with materials like plastic, Jell-O, and silicone, and it could make touch tracking a lot cheaper, too, since it relies on already available paint and parts, Zhang says. The project is being presented at the CHI computer-human interaction conference in Denver this week.

Zhang says the researchers bought some conductive spray paint—the one they purchased is typically used for coating electronics to lower electromagnetic interference—and sprayed a bunch of objects, including a steering wheel, a table, a toy dog, a map of the United States, and a wall. They attached electrodes to the perimeter of each object and connected the electrodes to a sensor board, which was itself connected to a laptop running software they developed.

When you touch one of these now-conductive surfaces, you distort the electrical field created by the sensor board and electrodes. The sensor board picks up these distortions, and software analyzes them to determine where touches occurred, and what should happen as a result (say, moving a virtual slider up or down, pressing a virtual button, or making a sound).

A demo video researchers made shows Electrick being used to do things like detect the presence of hands and gestures on a steering wheel and play sound effects when a user touched different parts of a Play-Doh snowman. Researchers also Electrick-ified a wall to control a light; the user could tap the wall to turn the light on or off, and slide a finger up and down to brighten or dim the bulb.

Zhang says the researchers found the Electrick-enabled devices to be about 99 percent accurate at determining whether or not someone was touching them. The average touch-tracking distance error is less than a centimeter, he says.

And while the system is currently wired, it could easily be made wireless, since the sensing board already has a Bluetooth module; Zhang says that could be used to punt data to a smartphone app.

Zhang would eventually like to make Electrick into a commercial product, but there are a number of issues that would need to be addressed first. The researchers don’t yet know how durable the technology is, even if their conductive paint were protected by another coating (Electrick can work this way, Zhang says). There’s also the problem of electromagnetic interference from electronics like microwaves and lights occasionally affecting the touch-tracking data, he says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.