How to Pull Water Out of Thin Air, Even in the Driest Parts of the Globe

Scientists have developed a device that can suck water out of desert skies, powered by sunlight alone. They hope that a version of the technology could eventually supply clean drinking water in some of the driest and poorest parts of the globe.

The device is based on a novel material that can pull large amounts of water into its many pores. According to a study published in the journal Science on Thursday, a kilogram of the material can capture several liters of water each day in humidity levels as low as 20 percent, typical of arid regions.

The technology could help address a big and growing problem. A report last year in Science Advances found that four billion people, nearly half in India and China, face “severe water scarcity at least one month of the year.” That means water shortages affect two-thirds of the world’s population. These shortages—and the resulting conflicts—are only expected to become more common in large parts of the world as climate change accelerates.

A team at MIT developed the technology with Omar Yaghi’s laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley. The key component is a promising class of synthetic porous materials called metal-organic frameworks, composed of organic molecules stitched together with metal atoms, which Yaghi pioneered (see “A Better Way to Capture Carbon”). The size and chemical character of the material’s pores can be customized to capture particular types of molecules or allow them to flow through. The material also has a massive surface area, on the order of a football field per gram, enabling it to bond with a large quantity of particles.

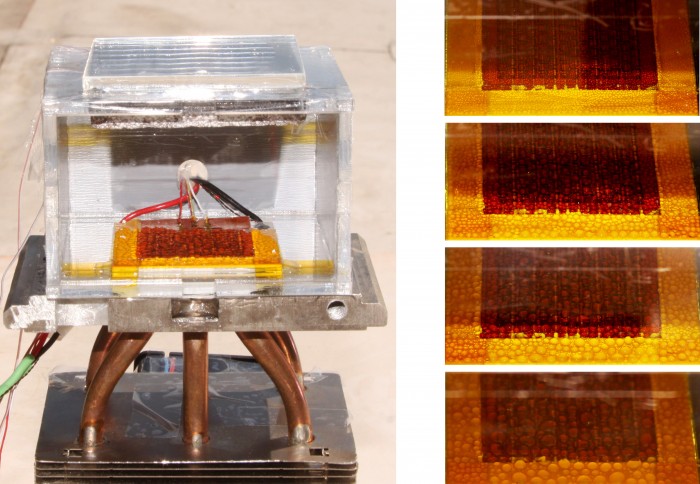

In this case, the scientists employed a previously developed version of the material that Yaghi optimized to efficiently capture water molecules. The prototype bonds with water at night or in shade. But during the day, sunlight hitting the material adds enough energy to convert the water molecules into vapor. In turn, they slip out of the material’s pores and into an adjacent acrylic enclosure. A condenser at the bottom of the vessel collects the water droplets and funnels them into a chamber below, from which clean water can be collected.

The process is completely passive, with no need for solar panels, batteries, or additional energy. Previous water-harvesting technologies have been limited to areas with fog or other high-moisture conditions.

Though they plan to continue refining the technology, they’re “not that far away” from a viable product, says Evelyn Wang, head of MIT’s device research laboratory. She notes that materials of this type are already being mass-produced, at increasingly affordable prices, by the German chemical giant BASF.

Yaghi says the technology could be paired with solar panels or other equipment to boost water production for industrial or agricultural purposes. But the big hope, he says, is that these devices could become household fixtures in poorer parts of the world. That would allow families to reliably produce their own water instead of rationing whatever they can carry, or whatever is available, from community wells.

Deep Dive

Climate change and energy

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Harvard has halted its long-planned atmospheric geoengineering experiment

The decision follows years of controversy and the departure of one of the program’s key researchers.

Why hydrogen is losing the race to power cleaner cars

Batteries are dominating zero-emissions vehicles, and the fuel has better uses elsewhere.

Decarbonizing production of energy is a quick win

Clean technologies, including carbon management platforms, enable the global energy industry to play a crucial role in the transition to net zero.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.