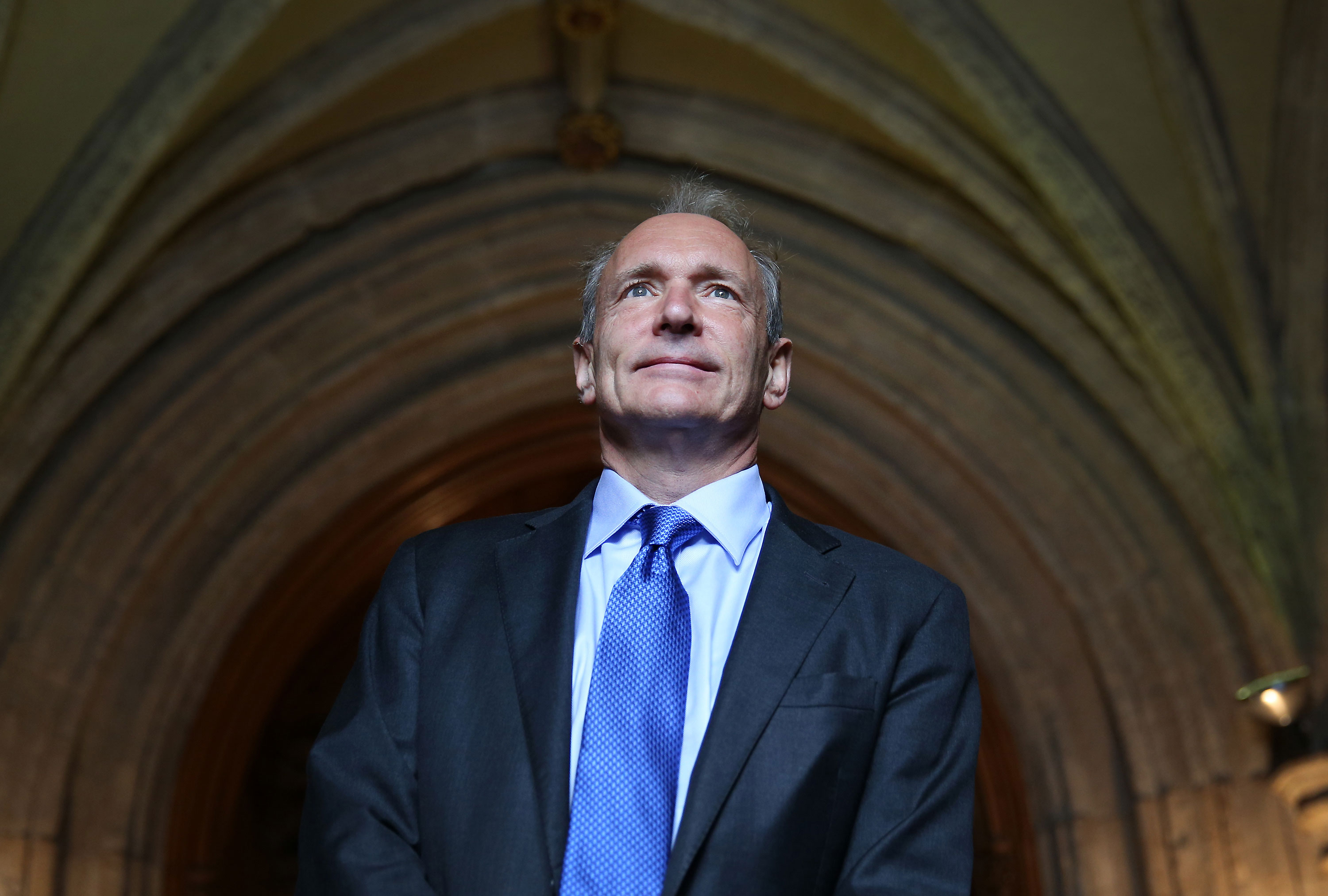

Web’s Inventor Tim Berners-Lee Wins the Nobel Prize of Computing

The man who made it possible for you to read this page just received the highest honor in computer science.

In 1989 Tim Berners-Lee, a programmer at the physics laboratory CERN, proposed a system that would allow computers to publish and access linked documents and multimedia over the Internet. Today the world runs on the Web, and Berners-Lee has been given the ACM Turing Award, considered something like the Nobel of computer science. He talked with MIT Technology Review about his invention’s past, present, and future.

Take us back to 1989. What was the problem you were setting out to solve when you started this work that led to the World Wide Web?

I was working at CERN and I was frustrated because people had brought along all kinds of wonderful computers—all different. Each would have some way of keeping track of documents and manuals and help files but they were all different as well. I felt, wouldn't it be wonderful if all of these systems could be somehow part of or considered part of one big meta-system?

The first thing we did was start a Web server at CERN for the phone book. It [previously] ran on a mainframe, which was a pain to have to log in to, and a lot of people just logged on to the mainframe to look up people’s phone numbers. The phone book got a few people to install a Web browser. It spread outside CERN in high-energy physics, and then ended up taking off exponentially.

Tim Berners-Leeu2019s career

1989

Writes a proposal for a “distributed hypertext system.”

1991

The first website goes online.

1994

Founds World Wide Web Consortium for Web standards.

2001

Calls for development of a Semantic Web readable by computers.

2009

Founds World Wide Web Foundation to widen Web access.

The Web now feels indispensable, and is part of many people’s daily personal and professional life. What still needs working on?

Now we have to talk about it as a human right. It’s not as basic as water, but the difference in economic and social power between someone who has it and someone who doesn’t means they’re massively disadvantaged. If you're in a village in Africa and you don't have access because you can't afford it, or you do have access and you can't use it because you're not literate, then this is a problem.

When we started the World Wide Web foundation [in 2009] we started pointing out that if 20 percent of the world has it, they owe the other 80 percent to try and get them connected as quickly as possible. [The UN said last November that 47 percent of the world’s population is now online.]

Looking ahead, you have spoken about the need for the Web to be “re-decentralized.” And you’re part of a community working on technology intended to do that. What’s the thinking behind this movement?

In the late ‘90s there was a massive excitement about what an incredibly empowering system this is, and de-centralization was an important part of that. Without asking anybody else, I could get a computer, put some software on it, plug it into the Internet, and I’d have a blog and a voice. People thought those voices would mount up and provide really exciting things. We have got great things like Wikipedia and crowdfunding, but a lot of people spend all their time in social network silos. A social network is disempowering because you put a lot of energy into it, all your personal data out there, and tell it who your friends are. You can only use that information inside the silo of that particular social network.

We had a few workshops, and we've got people working in the lab on things like Solid project at MIT, which is saying we could go to a world where everybody is in charge of their own data. Imagine if all the applications that you run point at data you control. That is an exciting new mode of operating.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.