How a Human-Machine Mind-Meld Could Make Robots Smarter

A secretive Canadian startup called Kindred AI is teaching robots how to perform difficult dexterous tasks at superhuman speeds by pairing them with human “pilots” wearing virtual-reality headsets and holding motion-tracking controllers.

The technology offers a fascinating glimpse of how humans might work in synchronization with machines in the future, and it shows how tapping into human capabilities might amplify the capabilities of automated systems. For all the worry over robots and artificial intelligence eliminating jobs, there are plenty of things that machines still cannot do. The company demonstrated the hardware to MIT Technology Review last week, and says it plans to launch a product aimed at retailers in the coming months. The long-term ambitions are far grander. Kindred hopes that this human-assisted learning will foster a fundamentally new and more powerful kind of artificial intelligence.

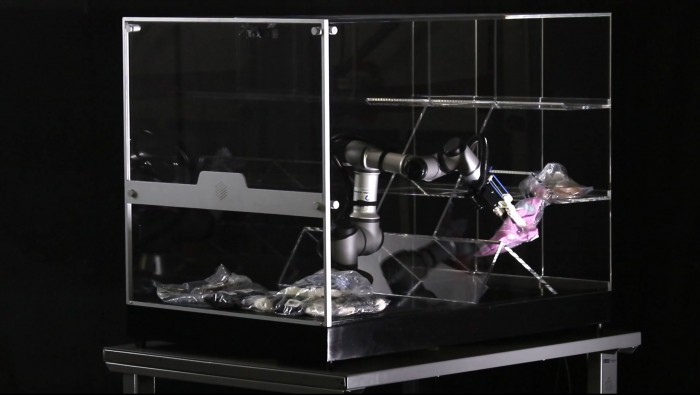

Kindred was created by several people from D-Wave, a quantum computing company based in Burnaby, Canada. Kindred is currently testing conventional industrial robot arms capable of grasping and placing objects that can be awkward to handle, like small items of clothing, more quickly and reliably than would normally be possible. The arms do this by occasionally asking for help from a team of humans, who use virtual-reality hardware to view the challenge and temporarily take control of an arm.

“A pilot can see, hear, and feel what the robot is seeing, hearing, and feeling. When the pilot acts, those actions move the robot,” says Geordie Rose, who is a cofounder and the CEO of Kindred, and who previously cofounded D-Wave. “This allows us to show robots how to act like people. Humans aren't the fastest or best at all aspects of robot control, like putting things in specific locations, but humans are still best at making sense of tricky or unforeseen situations.”

Kindred’s system uses several machine-learning algorithms, and tries to predict whether one of these would provide the desired outcome, such as grasping an item. If none seems to offer a high probability of success, it calls for human assistance. Most importantly, the algorithms learn from the actions of a human controller. To achieve this, the company uses a form of reinforcement learning, an approach that involves experimentation and strengthening behavior that leads to a particular goal (see “10 Breakthrough Technologies 2017: Reinforcement Learning”).

Rose says the system can grasp small items of clothing about twice as fast as a person working on his own can, while a robot working independently would be too unreliable to deploy. One person can also operate several robots at once.

Rose adds that Kindred is exploring all sorts of human-in-the loop systems, from ones where a person simply clicks on an image to show a robot where to grasp something, to full-body exoskeletons that provide control over a humanoid robot. He says that pilots usually learn how to control a remote robotic system effectively. “When you’re using the control apparatus, at first it’s very frustrating, but people’s minds are very plastic, and you adjust,” says Rose.

The technical inspiration for the technology comes from Suzanne Gildert, who was previously a senior researcher at D-Wave, and who is Kindred’s chief scientific officer. The company has been operating in stealth mode for several years, but drew attention when details of a patent filed by Gildert surfaced online. The patent describes a scheme for combining different tele-operation systems with machine learning. Indeed, Kindred’s vision for its technology seems to extend well beyond building robots more skilled at sorting.

“The idea was if you could do that for long enough, and if you had some sort of AI system in the background learning, that maybe you could try out many different AI models and see which ones trained better,” Gildert says. “Eventually, my thought was, if you can have a human demonstrating anything via a robot, then there’s no reason that robot couldn’t learn to be very humanlike.”

Most eye-catchingly, Kindred’s patent even described the possibility of having such systems controlled by animals such as monkeys. Gildert says this was a speculative idea, and no monkeys are currently employed by the company. However, she says the company does have a robotic cat, trained using reinforcement learning, wandering around its office.

Kindred is also a little unusual, in that its founders are physicists rather than roboticists or computer scientists by training. But Rose argues that this offers a unique and valuable perspective. “For computer scientists the line between a simulation and the real world is sometimes blurred,” he says. “We have strong preference for doing the sort of things we do in real robots in the real world.”

The approach Kindred is pursuing does seem to have huge potential. Ken Goldberg, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, who specializes in machine learning and robotics, says tapping into human skill will accelerate robot learning dramatically. Goldberg, who is working on a similar approach for robotic surgery, among other things, adds that having robots learn from humans is a very active area of research. “It’s at the core of what I believe is a big opportunity in robotics,” Goldberg says. “There’s a huge benefit to having human demonstration.”

But the technical challenges involved with learning through human tele-operation are not insignificant. Sangbae Kim, an associate professor at MIT who is working on tele-operated humanoid robots, says mapping human control to machine action is incredibly complicated. “The first challenge is tracking human motion by attaching rigid links to the human skin. This is extremely difficult because we are endoskeleton animals,” Kim says. “A bigger challenge is to really understand all the details of decision-making steps in humans, most of which happen subconsciously.”

The founders of Kindred hardly seem daunted, though. “Our goal is to deconstruct cognition,” Rose says. “All living entities follow certain patterns of behavior and action. We’re trying to build machines that have the same kind of principles.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.