The Startup That’s in Charge of the Biggest Private Satellite Fleet

When 88 of its tiny satellites were launched into orbit by India’s space agency earlier this month, startup Planet Labs helped set a world record for the largest one-time satellite deployment ever.

This new flock of satellites also gives the Earth-imaging startup a record of its own. With a total of 149 satellites in orbit, it now commands the largest private fleet in history.

Mike Safyan, Planet Labs’s director of launch and regulatory affairs, predicts that within three months this increased capacity will enable it to achieve its core mission of taking pictures of the entire surface of the Earth every day—something no other company has done thus far. Already, Planet Labs is imaging approximately 50 million square kilometers of the planet every day, which is double the entire surface area of North America.

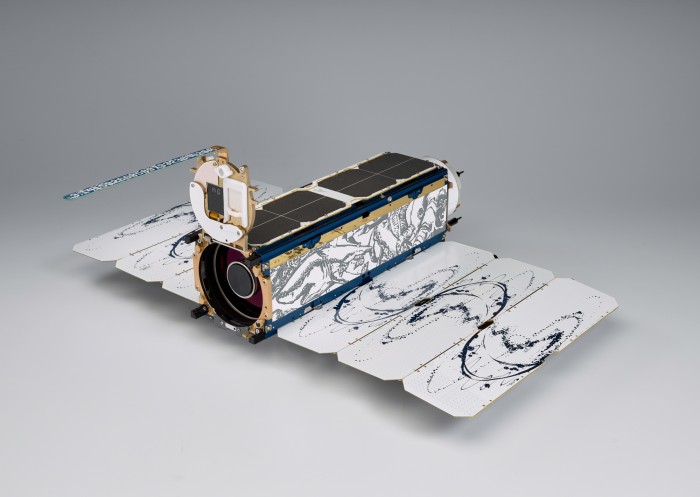

By decreasing the cost and size of their satellites—each one is roughly the size of a backpack and weighs around four kilograms—Planet Labs and a handful of competitors have helped change the economics of launching and maintaining large fleets of satellites.

“In contrast with somewhere like NASA, Planet is very agile,” says Simone D’Amico, assistant professor of aeronautics and astronautics at Stanford University and the founder of Stanford’s Space Rendezvous Lab. “They keep relaunching and upgrading frequently, and while the resolution is nothing exceptional, their coverage is incredible.”

Currently, the company’s clients include a broad range of corporate, government, and nonprofit entities in over 100 countries—ranging from agricultural businesses and consumer mapping companies to disaster relief agencies. By using software to automate the process of categorizing the massive flow of incoming imagery from satellites, Planet Labs can quickly build easily searchable data sets relevant to many industries.

The company’s images are used for all kinds of things. Some of Planet Labs’s clients use them to monitor ship traffic at ports as a proxy for a country’s economic health, gauge oil reserves by the angles of shadows cast by oil tanks, and monitor illegal mining operations and deforestation rates in places like Peru and Vietnam. After the April 2015 earthquake in Nepal, images from Planet Labs’s satellites helped rescue workers identify villages that were not on other maps of the affected regions.

The current resolution of images shot from Planet Labs’s collection of satellites is roughly three meters per pixel, which is sufficient to distinguish cars and trees, but not people. D’Amico notes that the startup’s recent acquisition of Google’s satellite imagery company Terra Bella (formerly known as Skybox Imaging) will allow it to increase this resolution to roughly one meter per pixel by using the larger apertures of the cameras on the Terra Bella satellites. The Terra Bella satellites could allow customers and researchers to notice an area of interest at the lower resolution before zooming in to examine it in greater detail. This level of resolution, combined with daily rescans of the entire Earth's surface, will create a massive and current data set of unprecedented proportions.

Many people compare satellites to various predatory birds, hovering and poised to strike, but cofounder Will Marshall and his team call theirs “doves” to reflect the altruistic and peaceful goals they hope their data will promote. Safyan says that they remain strongly committed to protecting forests, preventing illegal mining, protecting food security, and other environmental causes.

The higher resolution will likely raise privacy and security concerns, however, just as Google’s Street View did in its early days. Making public precise data on the locations of cell towers, nuclear power plants, or valuable antiquities, for instance, could pose obvious security risks. Albert Gidari, director of privacy at the Center for Internet and Society at Stanford Law School, predicts that Planet Labs will eventually need clear mechanisms for handling complaints and requests to blur or delete images.

Planet Labs does have an internal ethics board, and while Safyan described the application process for researchers to gain access to the company’s data as “light,” he says it “tries to ensure the data is not being resold to bad actors.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.