3-D-Printed Kidney Parts Just Got Closer to Reality

Using 3-D printing, scientists have created tiny, intricate tubes that work like key components of real kidneys.

Many more steps are needed before they can make artificial kidney replacement parts, but the result is important because it means that for the first time researchers have used 3-D printing to make kidney tissue that functions like the real thing. The inventors say that in the near term the artificial tissue could be used outside the body to assist in people who have lost renal function, and for testing the toxicity of new drugs.

Researchers have been trying to create artificial kidneys for more than 20 years, but re-creating a kidney’s complex three-dimensional structure and cellular architecture, which are crucial to its function, is extremely challenging. Still, the need is urgent. Roughly 10 percent of the world’s population suffers from chronic kidney disease. To stay alive, millions depend on dialysis, a time-consuming and physically demanding procedure in which blood is removed, run through a filtering device, and returned to the body. But dialysis machines aren’t nearly as effective as kidneys. And while roughly 16,000 people receive kidney transplants each year in the U.S., another 100,000 are waiting for donations.

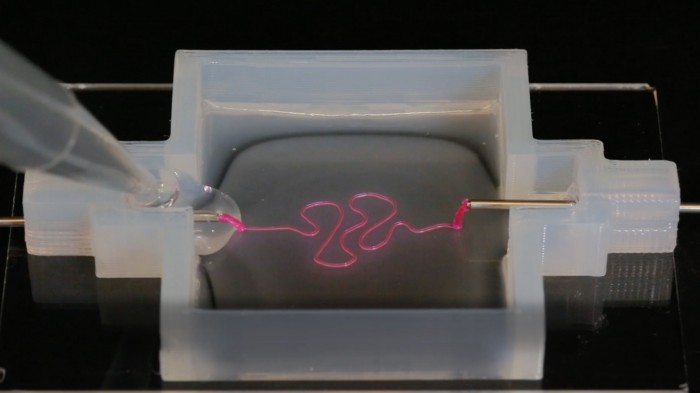

The new 3-D-printed kidney tissue is the work of the Jennifer Lewis lab at Harvard, which has developed an innovative approach to “bioprinting” tissue. The technique allows researchers to print complex structures found in different types of human tissue, as well as vascular systems necessary to keep such tissue alive. The printing method uses multiple kinds of gel-like “inks.” After printing, the researchers remove one of the inks, leaving hollow tubes. Then they add cells, which mature into tissue.

Lab tests show that the engineered tissue demonstrates real kidney function to a degree that has not been achieved before, say the researchers. In particular, they were able to make the proximal tubule, a component of a nephron, the basic functional unit of the kidney. Nephrons filter the blood, keeping the useful stuff for the body and excreting the rest. If scientists could build a nephron, in theory they could build kidneys, but that will require developing several additional interconnected parts, which will probably take many more years.

Still, this particular part of the nephron plays a key role in the process of reabsorbing nutrients, so the printed tissue could be medically useful, says Lewis, a materials scientist and professor of biologically inspired engineering at Harvard. For one thing, such tissue could be used to test potential drugs; some 20 percent of drugs in late-stage human tests fail because they are toxic to the kidneys. The artificial tissue could also be used in a device outside the body to assist in kidney dialysis. Developing such a device will take a few years at least, she says.

(Read more: “10 Breakthrough Technologies: Microscale 3-D Printing,” “Artificial Organs May Finally Get a Blood Supply”)

Deep Dive

Humans and technology

Building a more reliable supply chain

Rapidly advancing technologies are building the modern supply chain, making transparent, collaborative, and data-driven systems a reality.

Building a data-driven health-care ecosystem

Harnessing data to improve the equity, affordability, and quality of the health care system.

Let’s not make the same mistakes with AI that we made with social media

Social media’s unregulated evolution over the past decade holds a lot of lessons that apply directly to AI companies and technologies.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.