This AI Will Craft Tweets That You’ll Never Know Are Spam

Last month, some people tweeting about Pokémon Go became unwitting subjects in an experiment that could presage a worrying new kind of online attack.

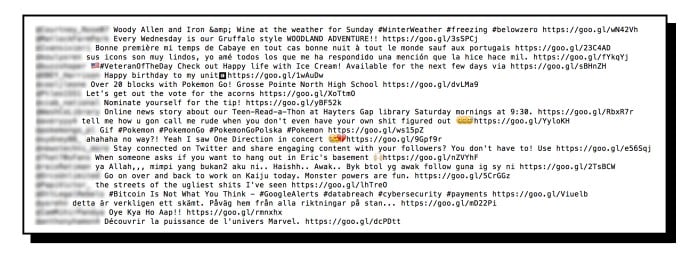

Industry researchers trained machine-learning software to write tweets like a human to reply to some people using the hashtag #Pokemon, in a demonstration of how advances in software that understands language could be used to trick people online. Roughly a third of people targeted by the software clicked on a benign link sent along by the software to test how convincing it was.

That’s much higher than the 5 to 10 percent success rate typical for automated “phishing” messages aimed at tricking people into clicking links to deliver malware or steal passwords, says John Seymour, a senior data scientist at security company ZeroFOX. The machine-learning system comes close to the roughly 40 percent success rate of “spearphishing” messages handcrafted to trick a specific person, he says.

“Spearphishing is highly manual and takes tens of minutes per target,” says Seymour. “This approach is almost as accurate and it’s automated, so it could be used at much larger scale.” The tweets don’t all look very polished, but they are effective, he says. Some people responded saying the link was broken and asking for it to be sent again.

Seymour presented the results of his experiments with colleague Phil Tully at the Black Hat computer security conference in Las Vegas on Thursday. The pair say their work shows that machine-learning technology could allow criminals to dramatically increase their success rates.

Phishing and spearphishing are already significant problems. Cisco reported last year that phishing messages sent via Facebook were the number one cause of unauthorized access to corporate networks.

The ZeroFOX researchers’ software, SNAP_R, can work in two ways. One uses the same artificial intelligence technique, deep learning, used by companies such as Google to make systems that can understand and translate language. It was trained on two million Twitter messages, allowing it to generate realistic-looking tweets of its own.

The system’s second mode is more targeted. It learns how to tweet by looking at an individual’s most recent tweets, and feeds them into an older technique called a Markov chain. It can then generate tweets similar to those written by the target, which a person might click thinking a message was written by a person with similar interests.

SNAP_R can also identify and target the most influential and active people talking about specific topics or using a specific hashtag. It looks for keywords such as “CEO” in a person’s profile, and indicators such as their number of followers. ZeroFOX is releasing a version of the software to help researchers think about the potential for these kinds of attacks and how to defend against them.

Mike Murray, vice president of security research at mobile security company Lookout, calls the prospect of using machine learning to automate the process of tricking people online “scary.” But he thinks it will take some time before that kind of approach is used to stage real attacks.

Despite recent progress, the best machine-learning techniques still require specialized expertise, and are far from perfect at generating language. Google is a leader in machine learning and language. But its Inbox app capable of generating responses to e-mails can only suggest short, one-sentence replies, says Murray. “If Google can’t generate more than a sentence, I probably can’t generate a really good phishing e-mail.”

ZeroFOX’s Tully isn’t predicting widespread criminal use of automated spearphishing tomorrow either. But he argues that machine-learning algorithms are getting easier to use, and needn’t perfectly master language to be successful on social media. People using Twitter are expecting to interact with strangers, and to see less-than-polished syntax, he says. “On Twitter the culture is so permissive and you don’t need to have perfect English or grammar.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.