Poll on Human Enhancement Shows Divided Public

Would you want surgeons to implant a microchip in your brain that boosted your recollection and recall? What about having a geneticist edit your child’s DNA to delete mutations associated with disease, or edit in tallness, cleverness, and quick-twitch muscles that would allow Junior to dash like the wind?

Right now, none of this is possible. Yet some scientists and futurists think bio-boosting technologies initially developed to help the sick and injured will be available to enhance the healthy within a few decades, forcing society to decide whether or not it approves.

This week, the Pew Research Center released the results of a large online survey asking American adults whether they’re ready to be bio-enhanced. The conclusion: the public remains wary.

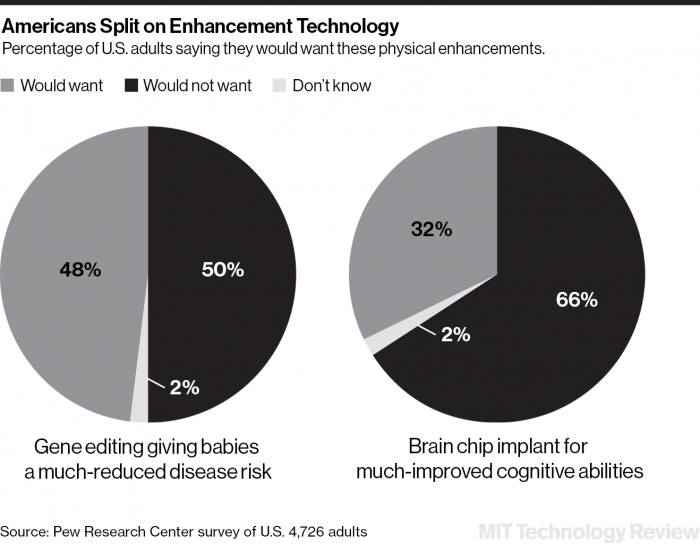

The survey asked 4,685 people if they were comfortable with three enhancements likely to be available in the near future: gene editing that gives babies a “much reduced” risk for disease; a chip implanted in the brain that improves cognitive abilities; and synthetic blood that substantially bumps up physical prowess.

The verdict was generally negative. Over 60 percent said that they were somewhat or very worried about these new technologies, and an equal number said that they would not want enhancements to their blood or brains. Opinion was evenly split on whether to enhance children’s DNA, with 50 percent opposed and 48 percent saying they’d do it—possibly because the question suggested that the technology would be used to cure disease, not to improve an already healthy child.

Admittedly, the public is only dimly aware of advances in biotechnology. Some 90 percent of those surveyed knew little or nothing about gene editing, while even fewer knew much if anything about early-stage research on brain implants.

This didn’t stop them from registering misgivings. These included a fear that only the rich will get anything good that comes of these technologies; that the enhanced will feel superior to the unenhanced; and that these improvements are morally unpalatable.

The poll found that religious Americans held the most negative views on enhancement, and that women were consistently more skeptical than men. It also found that the more people knew about technologies like gene editing, the more likely they were to approve of their use, although they felt better about a gradual rather than a radical change and wanted to be able to turn their bio-boosters on and off.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.