T-Cell Pioneer Carl June Acknowledges Key Ingredient Wasn’t His

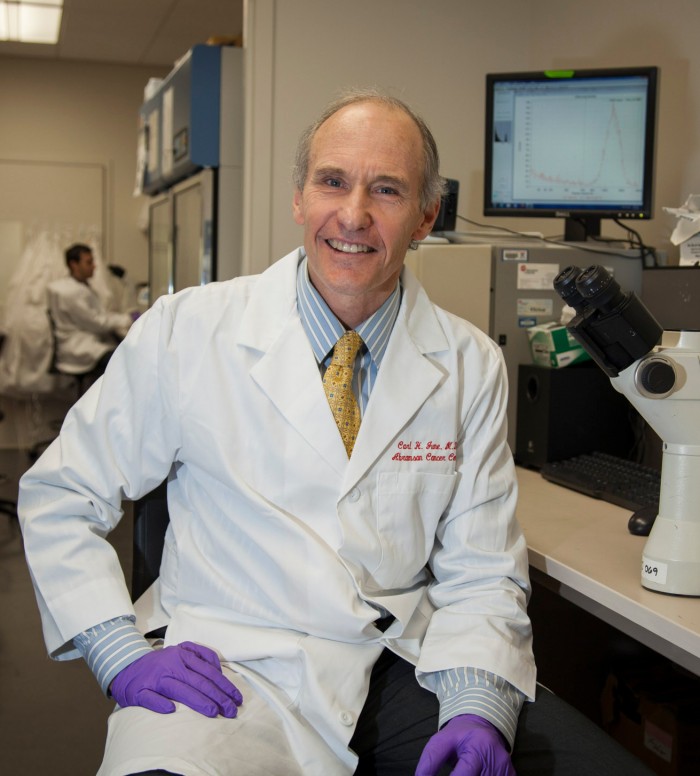

In corrections attached to three high-profile publications in the New England Journal of Medicine, the University of Pennsylvania’s star cancer scientist, Carl June, and his coauthors acknowledged they didn’t invent a key aspect of a breakthrough type of cancer therapy.

June has been hailed for his role in developing a new type of leukemia cure that uses engineered immune cells. The cells have added DNA instructions that direct them to attack a person’s cancer.

But now his papers, cited more than 2,300 times, according to Google Scholar, and which drew attention to revolutionary developments in cancer labs, have been amended to say they “omitted” an acknowledgment that the actual DNA was “designed, developed, and provided” by Dario Campana and Chihaya Imai, who worked at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

Intentional or not, June’s oversight was a doozy. Since his papers came out, the field of immune engineering has exploded. There are dozens of trials underway, a flood of federal grants, and billions of dollars in private investment at stake (see “10 Breakthrough Technologies 2016: Immune Engineering”).

St. Jude previously sued Penn when it learned the school was entering a commercial collaboration with the drug giant Novartis. That legal case was settled last year, with Novartis paying $12.5 million and shifting some future payments from Penn to St. Jude as well as to a startup named Juno Therapeutics.

But the scientific record remained uncorrected. Now June is publicly acknowledging that the actual business end of the T-cell invention wasn’t his, as many people have assumed.

While squabbles over credit among scientists aren’t unusual, lack of coӧperation and sharing among cancer labs has become a national concern. For instance, in January, U.S. Vice President Joe Biden picked Penn for the official launch of the administration’s new “moon shot” program to cure cancer, even touring June’s laboratory. In his remarks, Biden blamed “cancer politics” for holding back cures.

There’s no doubt June’s clinical trials at Penn have been important. The former Navy doctor and ultra-marathoner always seemed a step ahead of scientific rivals. In 2011, his team reported in the New England Journal of Medicine a near-miraculous turnabout for a patient with a blood cancer, and he popularized the breakthrough with vivid descriptions of T cells as “serial killers” that cause tumors “to melt away.”

For Penn, the success uncorked a tidal wave of prizes and funding, including more than $7 million in NIH grants in June's name since then. June rocketed to scientific stardom partly thanks to Emily Whitehead, a little girl cured by an infusion of T cells at Penn whose heartwarming case was described in scores of articles and the Ken Burns cancer documentary, The Emperor of All Maladies.

The paper that described Whitehead’s treatment, published in 2013, is among those now being corrected. Reached by e-mail in Singapore, where he now works, Campana said he was pleased with the results of Penn’s trials and those of other centers. “It’s been beneficial for immunotherapy,” he said. “But we developed this receptor. There is no question about that.”

The University of Pennsylvania provided a copy of a letter it sent last April to Jeffrey Dreazen, the editor of the journal, requesting the correction. It wasn't immediately clear why the journal delayed its publication.

The basic idea of T-cell therapy is to remove a patient’s white blood cells and then add a molecule to the cells which can stick onto cancer cells, lock-and-key style. The cells are then returned to the patient. But early studies flopped when the cells proved inactive.

Scientists realized they needed to add an additional signal—a kind of molecular tail jutting into the cell—to stimulate them to divide and attack the tumor. Credit for that idea belongs to several scientists, including Helen Finney, then of Celltech Therapeutics in London, and Michel Sadelain at Memorial Sloan Kettering in New York.

By 2003, Campana, who now works at the University of Singapore, had created one such molecular design and agreed to share it with Penn, after June asked for a copy. As is typical, the two institutions signed a contract known as a “material transfer agreement.” While public attention is often on patent disputes, such material agreements are far more common in science, used whenever researchers want to share DNA, cells, or even whole animals.

The dispute arose when June’s papers appeared to take credit for the DNA design and didn’t mention St. Jude’s contribution, though both scientific protocol and the materials agreement called for recognition of it.

In an interview last year, Sadelain, the Sloan Kettering researcher, said if such agreements between labs are disregarded, cancer research would become a chaos of broken trust “like the Middle East.” Reached by phone, Sadelain declined to comment further on the case.

Deep Dive

Biotechnology and health

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

An AI-driven “factory of drugs” claims to have hit a big milestone

Insilico is part of a wave of companies betting on AI as the "next amazing revolution" in biology

The quest to legitimize longevity medicine

Longevity clinics offer a mix of services that largely cater to the wealthy. Now there’s a push to establish their work as a credible medical field.

There is a new most expensive drug in the world. Price tag: $4.25 million

But will the latest gene therapy suffer the curse of the costliest drug?

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.