Toyota’s Billion-Dollar Bet

In November, Toyota gave birth to a unicorn: a billion-dollar, five-year enterprise called the Toyota Research Institute (TRI). Like Alphabet’s X division, TRI has a list of technology-driven moon shots that could transform society, from cars that are incapable of causing an accident to robots that would help older people.

For a company that began producing textile looms in the 1860s before shifting to automaking 70 years later, this could be the beginning of a whole new phase, Gill Pratt, the institute’s CEO, said at the Consumer Electronics Show in January. “It is entirely possible that robots will become for today’s Toyota what the car industry was when Toyota made looms,” he said.

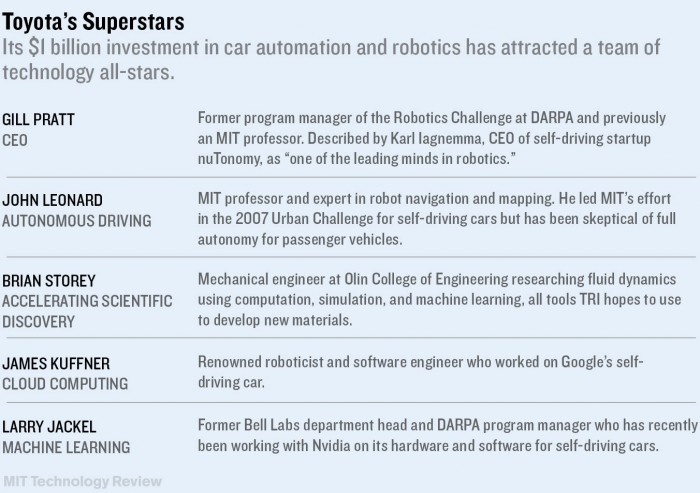

Pratt, a widely respected leader in robotics, came to TRI from DARPA, the Pentagon’s R&D arm, where he organized last year’s popular Robotics Challenge for humanoid rescue robots. He will now lead the world’s largest carmaker’s response to technology companies like Google, Apple, and Uber, which have all raided academia for autonomous-vehicle experts and begun developing their own robotic cars in the last few years.

But TRI’s approach to vehicular automation promises to be quite different, eschewing fully self-driving cars for a high-tech “guardian angel” that activates only when a collision is imminent.

“Perhaps one day we’ll get to the level of autonomy that Google talks about where you could go to sleep in your car or read a book,” says John Leonard, an engineering professor who managed MIT’s team in the DARPA Urban Challenge and will be in charge of automated driving at TRI. “In the shorter term, there’s an opportunity to do systems that work with and augment the driver. The human would still have primary responsibility for driving, but the system would run in parallel and jump in to try to prevent an accident.”

TRI will have facilities near Stanford and MIT, and some of its 30 initial projects will be carried out in collaboration with the two universities. One Toyota-funded effort already under way at the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Lab involves using machine-learning techniques to help automated vehicles cope more effectively with hazards they have not previously encountered. Another at MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory aims to allow automated systems to explain and justify their actions to a human driver.

The costs of making a semi-autonomous car may be difficult to recoup from a car owner, given that the safety systems might never activate. Pratt and Leonard nevertheless see opportunity for big improvements and say that TRI is shooting for reliability “a million times better” than what’s been achieved to date, so that autonomous cars might cause accidents only about once every trillion miles—the distance Toyota vehicles travel each year.

“It is entirely possible that robots will become for today’s Toyota what the car industry was when Toyota made looms.” —Gill Pratt

The team’s second job, developing robots for indoor mobility, is possibly even more ambitious. While roads are generally well-structured environments, with consistent rules that (most) users follow, every house or building has different lighting, furniture, belongings, and inhabitants. And where the ultimate aim of an autonomous car is to avoid other road users, domestic robots will have to interact with doors, appliances, people, and pets.

Among the challenges Leonard ticks off: locomotion, manipulation, robustness, and reliability.

With the institute barely two months old (it doesn’t even have a website yet), the full extent of its research focus has yet to be determined. “In Silicon Valley, a couple of people have an idea and it grows from there. We’re a unicorn right off the bat,” says Brian Storey, a professor of mechanical engineering at Olin College of Engineering, who has also joined the TRI team, “and there are not a lot of models of how to do that.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.