Experimental Fusion Reactor Switched On in Germany

Scientists in Germany today switched on a new kind of nuclear reactor, the latest experiment in the quest to produce clean, sustainable power from controlled nuclear fusion.

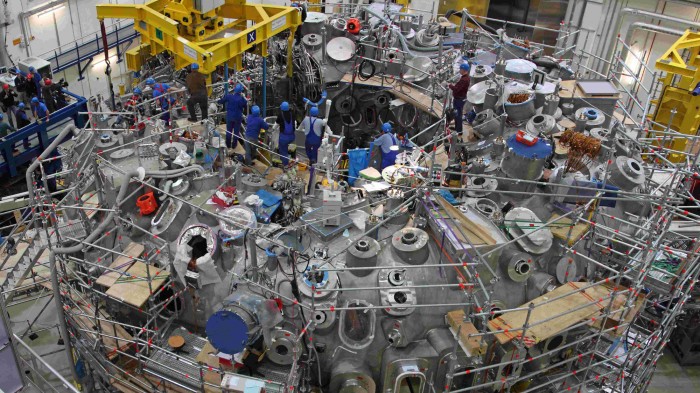

Chancellor Angela Merkel flipped the switch on the Wendelstein 7-X, a $435 million, doughnut-shaped apparatus built at the Max Planck Institute for Particle Physics in Greifswald. Hydrogen was injected into the device, superheated by microwaves until it became type of matter known as plasma for a fraction of a second.

Smashing hydrogen nuclei together releases huge amounts of heat—this is how the sun works—and not much radioactive byproduct. But despite decades of research, nobody has yet produced more energy from fusion reaction experiments than the energy put in.

Still, interest in fusion power is growing worldwide. A number of commercial and research efforts have made recent incremental achievements. And new corporate players have come into the mix, including an effort by Lockheed Martin.

Most efforts try to contain hot plasma within strong electric currents, using a doughnut-shaped device called a tokamak. The world’s largest tokamak is under construction in France at an international facility known as ITER that might cost $50 billion when completed.

Commercial players are exploring all kinds of exotic setups. Tri-Alpha, a company based near Irvine, California, is testing a linear-shaped reactor. Helion Energy of Redmond, Washington, is trying to use a combination of compression and magnetic confinement, while General Fusion, based in Vancouver, British Columbia, tries to control plasma using pistons to compress molten lead and lithium. The mixture also acts as a coolant that can be circulated to generate electricity through conventional steam generators and turbines.

These efforts are all many years away from providing meaningful amounts of electricity, as is the reactor that was tested today in Greifswald. Its design is something different again. Though similar in shape to a tokamak, it uses a complex system of magnetic currents to do the confinement. It is known, fittingly, as a stellarator.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.