Will Anybody Buy a Drone Large Enough to Carry a Person?

Attendees at the CES conference in Las Vegas will have an opportunity straight out of the Jetsons today: the chance to ride a quadcopter drone.

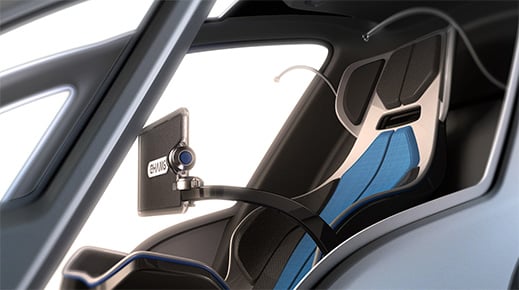

The 184, built by Chinese consumer drone maker Ehang, is a 440-pound quadcopter with an enclosed seating area for human passengers. It can carry a person up to 10 miles, or up to 23 minutes, at speeds around 60 miles per hour, according to Ehang cofounder and chief marketing officer Derrick Xiong. And just like a small drone, it is capable of flying at heights of up to 2.15 miles, though drone regulation would likely keep it at just several hundred feet.

If you are ready to race out and buy a 184, consider that they will likely cost between $200,000 and $300,000, keeping them out of reach of the average individual for now. Ehang does plan to ship them this year, and is preparing to begin accepting pre-orders.

“This is a commercialized product that comes with not only the body, but the failsafe system, even an air-conditioner system,” Xiong says.

Building a drone large enough to carry a person is not radically different from building a small consumer quadcopter. The 184 still flies with four arms and places the bulk of the weight at its center. Made of lightweight carbon fiber, the drone takes off and lands vertically and is battery-powered. According to Xiong, one of the largest changes comes into play in the software, where a fresh set of flight-control algorithms oversee the speed of the drone’s huge rotors.

The 184 is not the first rideable quadcopter. The 18-rotor Volocopter has been able to carry people since 2011, though it must be piloted manually. Lady Gaga once flew a few feet while suspended by a large drone at an album release party. In August, a Dutch engineer revealed an open-air quadcopter that could carry a person for up to 10 seconds.

Ehang expects the first adopters of the 184, which costs about the same as an entry-level helicopter, could use it as a tourist attraction or ferry between difficult-to-reach locations, such as islands. It could serve many of the same use cases as small consumer drones and helicopters, such as delivering people and supplies to remote locations or airlifting injured people to safety. Navigation is as simple as putting an address in Google Maps.

It is unclear exactly how a vehicle like the 184 would be regulated in China or elsewhere, but Xiong said Ehang is working with mayors of cities in several countries to consider the technology. Like self-driving cars and consumer drones, it would likely require fresh legislation.

Public trust is a major barrier to adoption of technology like the 184, according to Stanford Intelligent Systems Laboratory director Mykel Kochenderfer. Users need to be sure of the reliability of the vehicle’s frame, propulsion system, and resistance to hacking. Overall, it’s difficult to foresee every single possible failure.

“Nevertheless, I’m sure that there will be some enthusiastic early adopters; whether that will be sufficient to get the business off the ground remains to be seen,” Kochenderfer says. “NASA has been supporting research on future concepts for personal air vehicles and autonomy for some time now, but it will take time for this technology to catch on.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.