Data Mining Reveals How Smiling Evolved During a Century of Yearbook Photos

Data mining has changed the way we think about information. Machine-learning algorithms now routinely chomp their way through data sets of Twitter conversations, travel patterns, phone calls, and health records, to name just a few. And the insights this brings is dramatically improving our understanding of communication, travel, health, and so on.

But there is another historical data set that has been largely ignored by the data-mining community—photographs. This presents a more complex challenge.

For a start, the data set is vast, spanning 150 years since the dawn of photography. What’s more, the information it contains can be hard to distill, often because it is too complex or too mundane to describe in words.

Today, that changes thanks to the work of Shiry Ginosar at the University of California, Berkeley, and a few pals, who have pioneered a machine-vision approach to mining the data in ordinary photographs.

These guys start with a relatively simple database—American high-school yearbook photographs dating back to 1905. These yearbook photos have been digitized on large scale by local libraries all over the U.S. and show full frontal photos of individuals in a standard pose.

Ginosar and co downloaded over 150,000 of these portraits. After removing those that were not full frontal portraits, they were left with some 37,000 images from more than 800 yearbooks from 26 U.S. states.

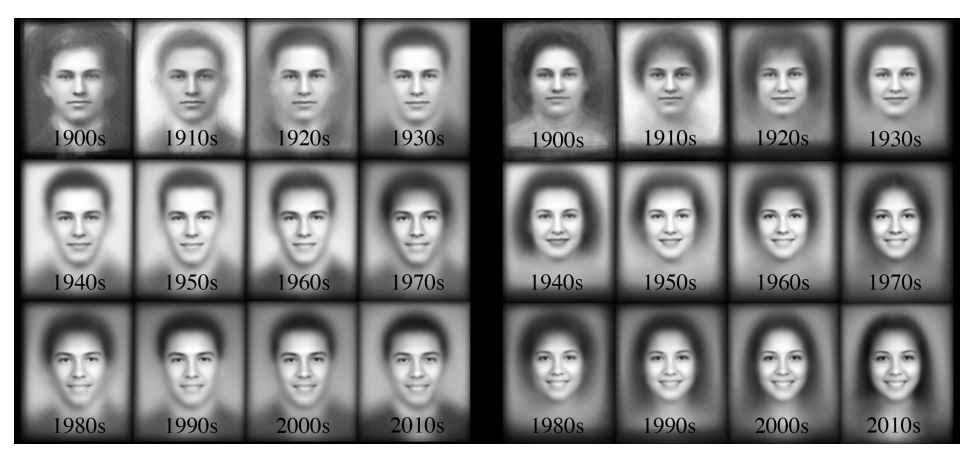

They then grouped the portraits by decade and superimposed the images to produce an “average” face for each period. This process revealed other “average” features for each period such as hairstyle, clothing, style of glasses, and even average facial expressions. The image above shows these averages for each decade for men and women.

The results make for interesting reading. A particularly striking feature is the evolution of smiling in yearbook photographs. Ginosar and co say that in the years after the invention of photography, most people adopted the same pose they would have used for a painted portrait—a neutral expression that would be easy to hold for a long period.

“Etiquette and beauty standards dictated that the mouth be kept small—resulting in an instruction to “say prunes” (rather than cheese) when a photograph was being taken,” say Ginosar and co.

But that changed during the 20th century, when photography became more popular. In particular, the photography company Kodak used advertising to popularize the idea of smiling in photos so that the images recorded happy memories.

Whatever the reason, smiling has become much more prominent. “These days we take for granted that we should smile when our picture is being taken,” say Ginosar and pals.

And the data backs that up. The team developed an algorithm for determining the degree of lip curvature in the photographs and this showed a clear trend in increasing smile intensity over time.

The data also reveals another trend. “Women significantly and consistently smile more than men,” they say. This is not a new discovery—indeed it has been discussed for decades.

But in the past, the data could only be assembled by painstaking manual analysis of thousands of photos. A comparison with Ginosar and co’s technique shows its power. ”By use of a large historical data collection and a simple smile-detector we arrived at the same conclusion with a minimal amount of annotation and virtually no manual effort,” they say.

The data also reveals other trends. Ginosar and co point to the evolution of hairstyles, saying their data sets pick out: “The finger waves of the ’30s. The pin curls of the ’40s and ’50s. The bob, “winged” flip, bubble cut of the ’60s. The long hair, Afros, and bouffants of the ’70s. The perms and bangs of the ’80s and ’90s, and the straight long hair fashionable in the 2000s.”

Other things haven’t changed though. For example, the default dress code for men has remained the suit throughout the 20th century.

Of course, there are some limitations to this dataset. For example, less than 10 percent of American 18-year-olds graduated from high school in the 1900s, but this rose to more than 50 percent at the end of the 1960s. What’s more, the African American population was not represented in schools until the middle of the 20th century, creating a significant bias in the data set.

Nevertheless, the works provides a fascinating insight into the way photographic data sets might be exploited in future. And the evolution of smiling and hairstyles is just the beginning.

It’s not hard to think of other features that could be extracted from seemingly mundane images. For example, the history of family snapshots probably contains a vast database of information about the evolution of wallpaper patterns, clothing, children’s toys, and so on.

For the moment, this database is largely untapped. But that looks set to change in the not too distant future.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1511.02575: A Century of Portraits: A Visual Historical Record of American High School Yearbooks

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.