This Glowing Rock Wants to Monitor Your Internet of Things

There’s a smooth, dark brown stone sitting in front of me on the table with a bright circle pulsing on its face—a signal, apparently, about the security status of Yossi Atias’s fictional Internet-connected home.

Atias is the CEO and cofounder of an Israeli startup called Dojo-Labs, one of numerous companies trying to secure the so-called Internet of things. The stone is part of its first security product, Dojo; it gets alerts via low-energy Bluetooth from a white, rectangular device that plugs into your Wi-Fi router and monitors the network activity of Internet-connected home gadgets like smart lights, TV sets, and alarm systems.

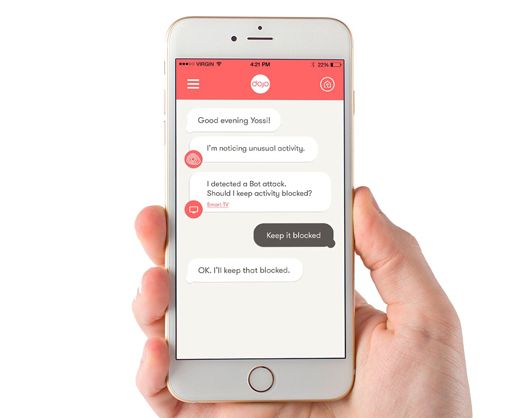

When something out of the ordinary happens—for example, a stranger tries to remotely disable your home alarm system, which Atias demonstrates by hacking into an alarm set up at his company’s office in Israel—Dojo reacts automatically to stop it and sends you a message through its smartphone app to let you know what’s going on. The glowing ring on the stone, meanwhile, would change from white (an indication that everything’s fine) to orange.

Connected home gadgets are growing at a rapid clip: tech market researcher Gartner estimates that we’ll have 6.4 billion connected devices next year—30 percent more than in 2015—and that this number will rise to nearly 21 billion by 2020 as more cars, watches, and lights connect to the Internet.

Yet despite this growth, Internet-of-things security “is very much a mess,” says Prabal Dutta, an assistant professor at the University of Michigan who studies the space. Connected home devices often include minimal security measures, and this, plus their increasing ubiquity, makes them attractive targets for hackers. Plenty of security researchers have shared examples of how easy it is to hack everything from baby monitors to traffic lights, and reports abound of security weaknesses in connected devices.

Dojo-Labs is trying to simplify the security for these devices. The user doesn’t have to do much other than plug in the white box (which connects with the company’s remote servers) and install the smartphone app. The glowing stone, meanwhile, is an attempt to make security less abstract; it’s a sort of pet rock, Atias explains.

“First, we inform you so you know what’s going on,” he says. “Then we give you the choice to control your own privacy and security.”

Dojo, which is available for pre-order from Amazon on Thursday, will cost $99 and start shipping to customers in March; the price, which will go up to $199 in March, includes a year of service from Dojo-Labs. After that, users will have to pay a monthly fee.

While Dojo starts out by profiling each smart-home device to get a sense of how it should behave, over time, the system will get smarter as it tracks more activity from more users, Atias says. He says that because it’s monitoring network metadata (things like where data is coming from or going to, and the volume of such data), Dojo will work atop existing security that may be in place on individual devices, even those that use data encryption.

And Dojo-Labs isn’t alone in developing such a security approach. Finnish online security company F-Secure also announced this month that it will sell a similar product called Sense; it, too, will come with a year’s worth of that company’s subscription service.

Dutta thinks such intrusion-detection systems could be useful for securing connected home devices. But while companies routinely pay for network security, it’s likely to be hard to convince individuals to do so until something bad happens. Additionally, if the system sounds a handful of false alarms, users won’t trust it, he notes.

Still, he says, “I would laud them for putting a stake in the ground, for saying here’s something we can do.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.