The Ad Blocking Kingpin Reshaping the Web as He Prefers It

The very foundation of the free Web is at risk, and Wladimir Palant is partly to blame. Now he thinks he can fix it.

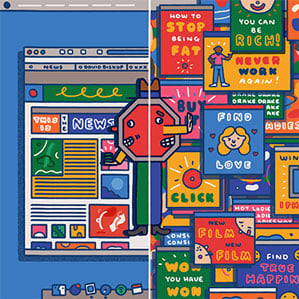

The problem, as he sees it, is an “outright war” between online advertisers and the rest of us. As intrusive online advertising has proliferated—in banners, pop-ups, and videos that distract readers, cover up content, clog the Internet, and track your Web browsing—easy-to-install programs that block those ads have soared in popularity. Take away the ads, and so goes the revenue that makes huge parts of the Web possible.

Palant is the creator of Adblock Plus, which has 60 million active users, making it the most popular of the ad blockers. That gives Palant, a shy, privacy-minded software developer from Moldova, and his company, Eyeo, an outsize role in determining the future of Internet advertising. His solution is to force a truce by letting only certain ads through the blocker. In other words, his goal is to save the Web by making ads less annoying.

In the process, Palant, 35, has made enemies, including publishers in Germany who have taken Eyeo to court, so far unsuccessfully. His opponents object to the fact that while Adblock Plus is open-source and free to download, Palant has figured out a clever way to profit from the détente he has forced with ad purveyors. Though one can choose to have Adblock Plus strip out all ads from Web pages, the application will, by default, let through ads that are part of Eyeo’s so-called Acceptable Ads program. To be in the program ads must be static, mainly text, and positioned in a way that doesn’t distract from the primary content on the page. Although small websites can apply for free to be included in the program, around 700 “larger properties,” including Google and Amazon, have to pay. Unlike the Acceptable Ads criteria themselves, who pays, and who doesn’t, isn’t so transparent.

Palant’s plan feels logical. If advertising is less intrusive and doesn’t invade one’s privacy, fewer people will be compelled to block every ad. We could all win: users get to keep their free content, advertisers maintain a low-cost way to reach customers, and publishers can fund their work. But who gets to decide what counts as an appropriate ad?

No-win battle

The Eyeo offices are located on the eighth floor of a generic office building in central Cologne, Germany, about 15 minutes by foot from the city’s iconic cathedral. Though it is the leading ad blocking company, Eyeo has all the signs of a scrappy startup: roughly 50 young employees representing a dozen countries, a spare room set aside for daily ping-pong battles, and a variety of Nerf projectiles and launchers.

One of the first employees I meet is a Spaniard who goes by “The Gatekeeper” (real name: Manuel Caballero) because of his role in shepherding websites through the Acceptable Ads program. Another is Job Plas, who is helping to set up an independent board intended to oversee the Acceptable Ads program.

Then there is Palant. His involvement in ad blocking dates to 2004—a decade after the first banner ad went online—when he was just another Web surfer annoyed by ads. To deal with the problem he tried out a free, early browser extension—an add-on anyone can download—called Adblock. “But it had a huge disadvantage,” Palant says, “namely that it would not block anything, only hide it.” The ads were still being downloaded in the background—causing pages to load slowly, keeping track of his browsing interests, and wasting his computer’s processing cycles and battery life.

When Palant’s suggestions for improving Adblock were rebuffed by its mysterious developer, known as “rue,” Palant decided to build a better mousetrap. Luckily, there was a competing extension called Adblock Plus, created when Adblock hadn’t been ready for the release of Firefox 1.5. Its lead developer agreed to transfer the project to Palant for a rewrite. On January 17, 2006, Palant released his own, totally new version of Adblock Plus. It was an instant success.

That is where Palant expected the story to end. “My original idea was that I would improve it. I would get it into decent shape. And then it would just go by itself, more or less,” he says. In theory, this was possible because Adblock Plus was being maintained by an open-source community. But Palant says things didn’t work out the way he envisioned.

Within a year Adblock Plus had been named by PC World as one of 2007’s best products (just behind Netflix’s streaming service)—and ignited its first, now instructive, controversy. A religious blogger named Danny Carlton was incensed by his potential loss in revenue, writing: “Using ad blocking software to block all ads is stealing, no ifs, ands or buts.” In response, Carlton blocked Firefox users from being able to access his blog—a move widely ridiculed—denying himself the prospect of a quarter of the world’s Web traffic.

“This was a very beneficial thing for us,” Palant recalls now. The media attention brought a wave of users, and drew Palant ever deeper into the project. Still, Adblock Plus was a hobby for him; his real job was developing software like a music app called Songbird and projects for TomTom GPS devices.

That changed in 2010, when outside investment allowed Palant to quit his day job and work on the extension full-time. Shortly afterward, Adblock Plus introduced its most controversial feature: Acceptable Ads. Having this “whitelist” of ads that would stay unblocked, says Palant, was a way to avert a no-win battle between publishers and users.

Protection schemes

To hear Palant talk about the whitelist feature today, Acceptable Ads has both an underlying ethical premise (online journalism and blogging rely on ads to stay afloat) and a pragmatic one (Eyeo and Adblock Plus need to pay people like The Gatekeeper to determine whether ads are obnoxious or not). Palant had toyed with other ways to run Adblock Plus—including micro donations and asking users to disable the extension for certain websites—but ultimately decided to charge large organizations to be part of Acceptable Ads, while allowing around 700 others, by the latest count, into the program for free. “I realized that finding that middle ground between publishers and users would require resources a hobby product could not afford,” says Palant. If Eyeo didn’t charge larger companies, it wouldn’t be able to offer the Acceptable Ads program at all—removing any incentive for online ads to become less intrusive.

But the appearance of a conflict of interest, and critical lapses in transparency—like not initially announcing that Adblock Plus was charging millions of dollars to some companies in the Acceptable Ads program—led some users to feel betrayed, and some publishers to compare Eyeo’s business model to a mafia protection scheme.

To combat such accusations, Eyeo announced in October that it would remove itself from determining which ads are acceptable: “We’re inviting a completely independent review board to take over, enforce and oversee our Acceptable Ads initiative.” Eyeo can still collect fees, though, from the companies that pass the board’s review.

Palant says this will bring his company’s goals back into line with his own personal vision for the future of the Internet. “What I really would like to see is that the Web as a whole takes a step back and develops a meaningful compromise between what the websites need and what publishers need,” Palant tells me.

If Adblock Plus has the impact he hopes it will, Palant says, even people who surf the Web “unprotected” will enjoy the benefits of advertisers tacking in the direction of the Acceptable Ads program.

There are signs Palant might be on to something. In response to the rise of ad blockers, an ad-industry organization, the Interactive Advertising Bureau, is now encouraging advertisers to post ads that have fewer bandwidth-hogging bells and whistles and behavior-tracking technologies. Acknowledging that advertisers have “steamrolled the users, depleted their devices, and tried their patience,” Scott Cunningham, the IAB’s senior vice president of technology and ad operations, in October described a set of principles for ads that he thinks consumers won’t choose to block.

If the IAB initiative catches on, there could be a battle over who gets to play gatekeeper for ads. The IAB wants a say, and Eyeo does, too. Palant says he’s distancing himself personally from that role—though the Adblock Plus system he has built is undeniably at the heart of any Acceptable Ads initiative being picked up by an independent board.

The alternative, warns Palant, is that if ads don’t improve or get worse, and users invoke the nuclear option of all-out ad blocking, the economic model of the Web disappears without something that can fully take its place. “Ads are horrible,” Palant says with a sigh, “but they are what we have.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.