An “Almost Perfect” Battery

Everyone wants better batteries, whether to make smartphones last longer or to drive an electric car farther. So researchers around the world are focused on boosting the amount of energy that batteries can hold while improving their safety.

Now researchers at MIT, working with Samsung and other collaborators, have developed a new approach that could make it practical for today’s most common rechargeable batteries to use a solid material for the electrolyte, the component that transports charged particles between two electrodes as a battery charges and discharges. The idea is that a solid electrolyte, rather than the liquid used today, could greatly improve battery life and safety—while significantly increasing the amount of energy stored in a given space.

The team, led by MIT postdoc Yan Wang and Gerbrand Ceder, a visiting professor of materials science and engineering, aimed to develop solid-state electrolytes for lithium-ion batteries. The electrolyte now used in such batteries—typically a liquid organic solvent—has been responsible for overheating and fires that, for example, temporarily grounded all of Boeing’s 787 Dreamliner jets, Ceder explains. Others have sought a solid replacement for the liquid electrolyte, but this group is the first to show that a solid material can conduct ions fast enough to work well in the types of batteries used today.

“All of the fires you’ve seen, with Boeing, Tesla, and others—they are all electrolyte fires,” Ceder says. “The lithium itself is not flammable in the state it’s in in these batteries.” With a solid electrolyte, “there’s no safety problem—there’s nothing there to burn,” he says.

The proposed solid electrolyte also holds other advantages. “With a solid-state electrolyte, there’s virtually no degradation reactions left,” Ceder says. And that means such batteries could last through “hundreds of thousands of cycles.”

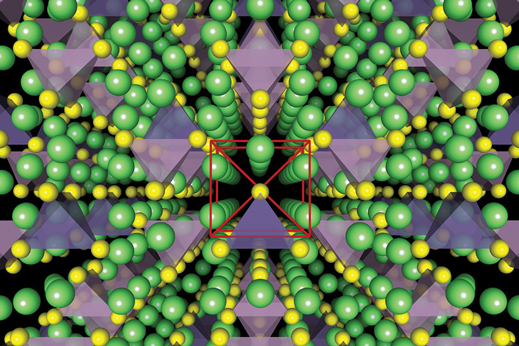

The team’s initial findings focused on superionic lithium-ion conductors, which are compounds of lithium, germanium, phosphorus, and sulfur. But the principles derived from this research could lead to even more effective materials, the team says.

Solid-state electrolytes could be “a real game-changer,” Ceder says, solving “most of the remaining issues” in battery lifetime, safety, and cost. The result, he says, could be “almost a perfect battery.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.