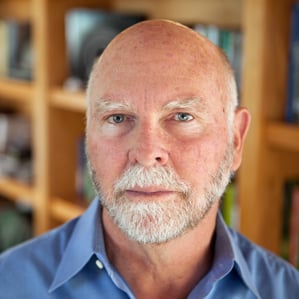

J. Craig Venter to Offer DNA Data to Consumers

Fifteen years ago, scientific instigator J. Craig Venter spent $100 million to race the government and sequence a human genome, which turned out to be his own. Now, with a South African health insurer, the entrepreneur says he will sequence the medically important genes of its clients for just $250.

Human Longevity Inc. (HLI), the startup Venter launched in La Jolla, California, 18 months ago, now operates what’s touted as the world’s largest DNA-sequencing lab. It aims to tackle one million genomes inside of four years, in order to create a giant private database of DNA and medical records.

In a step toward building the data trove, Venter’s company says it has formed an agreement with the South African insurer Discovery to partially decode the genomes of its customers, returning the information as part of detailed health reports.

The deal is a salvo in the widening battle to try to bring DNA data to consumers through novel avenues and by subsidizing the cost of sequencing. It appears to be the first major deal with an insurer to offer wide access to genetic information on a commercial basis.

Jonathan Broomberg, chief executive of Discovery Health, which insures four million people in South Africa and the United Kingdom, says the genome service will be made available as part of a wellness program and that Discovery will pay half the $250, with individual clients covering the rest. Gene data would be returned to doctors or genetic counselors, not directly to individuals. The data collected, called an “exome,” is about 2 percent of the genome, but includes nearly all genes, including major cancer risk factors like the BRCA genes, as well as susceptibility factors for conditions such as colon cancer and heart disease. Typically, the BRCA test on its own costs anywhere from $400 to $4,000.

“I hope that we get a real breakthrough in the field of personalized wellness,” Broomberg says. “My fear would be that people are afraid of this and don’t want the information—or that even at this price point, it’s still too expensive. But we’re optimistic.” He says he expects as many as 100,000 people to join over several years.

Venter founded Human Longevity with Rob Hariri and Peter Diamandis (see “Microbes and Metabolites Fuel an Ambitious Aging Project”), primarily to amass the world’s largest database of human genetic and medical information. The hope is to use it to tease out the roles of genes in all diseases, allow accurate predictions about people’s health risks, and suggest ways to avoid those problems. “My view is that we know less than 1 percent of the useful information in the human genome,” says Venter.

The company this year began accumulating genomes by offering to sequence them for partners including Genentech and the Cleveland Clinic, which need the data for research. Venter said HLI keeps a “de-identified” copy along with information about patients’ health. HLI will also retain copies of the South Africans’ DNA information and have access to their insurance records.

“It will bring quite a lot of African genetic material into the global research base, which has been lacking,” says Broomberg.

Deals with other insurers could follow. Venter says that only with huge numbers will the exact relationship between genes and traits become clear. For instance, height—largely determined by how tall a person’s parents are—is probably influenced by at least hundreds of genes, each with a small effect.

Citing similar objectives, the U.S. government this year said it would assemble a study of one million people under Obama’s precision-medicine initiative (see “U.S. to Develop DNA Study of One Million People”), but it may not move as fast as Venter’s effort.

HLI has assembled a team of machine-learning experts in Silicon Valley, led by the creator of Google Translate, to build models that can predict health risks and traits from a person’s genes (see “Three Questions for J. Craig Venter”). In an initial project, Venter says, volunteers have had their facial features mapped in great detail and the company is trying to show it can predict from genes exactly what people look like. He says the project is unfinished but that just from the genetic code, HLI “can already describe the color of your eyes better than you can.”

Venter also said that this October the company will open a “health nucleus” at its La Jolla headquarters, with expanded genetic and health services aimed at self-insured executives and athletes. The center, the first of several he hopes to open, will carry out a full analysis of patients’ genomes, sequence their gut bacteria or microbiome, analyze more than two thousand other body chemicals, and put them through a full-body MRI scan. “Like an executive physical on steroids,” he says.

The health nucleus service will be priced at $25,000. These individuals would also become part of the database, Venter said, and would receive constant updates as discoveries are made.

While the quality of Venter’s science is not in much doubt, this is the first time since he was a medic in Vietnam that he’s doled out medicine directly. “I think it’s a good concept,” says Charis Eng, chair of the Cleveland Clinic’s Genomic Medicine Institute, which collaborates with Venter’s company. “But we who practice genomic medicine—we say HLI has absolutely no experience with patient care. I want to inject caution: it needs to be medically sound as well as scientifically sound.”

Venter has a history of selling big concepts to investors and then using their money to carry out exciting, but not necessarily profitable, science. In 1998 he formed Celera Genomics to privately sequence the human genome, but he was later booted as its president when its business direction changed. The economics of his current plan are also uncertain. Venter’s pitch is that with tens of thousands and ultimately a million genomes, he will uncover the true meaning of each person’s DNA code. But all those discoveries lie in the future.

And at a cost of around $1,000 to $1,500 each, a million completely sequenced genomes add up to an expense of more than a billion dollars. HLI has so far raised $80 million, but Venter says he is now meeting with investors in order to raise far larger sums.

Venter says he intends to offer several other common kinds of testing, including pre-conception screening for parents (to learn if they carry any heritable genetic risks), sequencing of tumors from cancer clinics, and screening of newborns. Those plans could bring HLI into competition with numerous other startups and labs that offer similar services.

“It would be just one more off-the-shelf genetic testing company, if the entire motivation weren’t to build this large database,” he says. “The future game is 100 percent in data interpretation. If we are having this conversation five to 10 years from now, it’s going to be very different. It will be, ‘Look how little we knew in 2015.’”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.