Seven over 70

Every year we celebrate 35 innovators under the age of 35. We choose to write about the young simply because we want to introduce you to the most promising new technologists, researchers, and entrepreneurs.

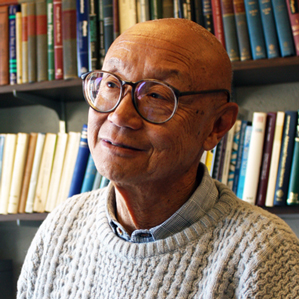

But older people are, of course, just as capable of new thinking as the young. Below are seven innovators over the age of 70, still working.

1. Bob Kahn, who is 76, invented (with Vint Cerf) the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and the Internet Protocol (IP), the communication protocols that relay data around the Net, and was responsible for the systems design of the Arpanet, the first packet-switched network. Today he is the chairman and CEO of the Corporation for National Research Initiatives (CNRI), an organization he founded that funds and develops network-based technologies. His most recent research has focused on the development of a “digital object architecture,” which enables various information systems and resources to work together.

2. Sidney Yip, born in 1936, is a professor emeritus of nuclear science and engineering at MIT. After notionally retiring in 2009—having taught for 44 years and published more than 300 papers and the Handbook of Materials Modeling (2005), the standard reference book in the field—he continues to do important research. For instance, he suggested (with MIT senior research scientist Roland Pellenq) a new recipe for concrete that increases its strength while reducing the carbon emissions associated with producing cement.

3. Judith Jarvis Thomson, 85, another of MIT’s professors emeriti, is a philosopher best known for the elaboration of thought experiments called “trolley problems,” which test our moral intuitions. In the most famous trolley problem of all, Thomson asks her readers to imagine pushing a fat man onto a track in order to stop a runaway trolley from running over five people. She remains keenly interested in questions of rights and normativity (whether, ethically, one ought to do or refrain from doing something). Trolley problems are useful in thinking how autonomous vehicles and military robots could be programmed to behave in ways consistent with most people’s moral intuitions.

4. The great chemist John Polanyi, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1986 for his contributions toward understanding the dynamics of elementary chemical processes, is still busy at age 86. His work at the University of Toronto uses scanning tunneling microscopes to study chemical reactions that might help us build devices at very small scales. Polanyi’s father, Michael, the Hungarian chemist, philosopher, and economist, defended the liberty of scientific thought; the son, too, is concerned with public affairs, and he often speaks or writes about nuclear weapons and social justice.

5. Paul Greengard, born in 1925 and a 2000 Nobel laureate in medicine, still works on average six days a week, at Rockefeller University, where he researches what causes brain disorders like Alzheimer’s disease and schizophrenia. One major area of research in Greengard’s lab is the search for the cellular and molecular basis of depression; his researchers recently described a protein that plays a central role in the regulation of moods.

6. Helen Murray Free, 92, developed a series of self-testing kits for diabetes while working at Miles Laboratories in the second half of the last century. The tests transformed the way people with diabetes monitor their disease, helping make it into a manageable condition. Since retiring in 1982, she has devoted herself to promoting science education, particularly for young women and minorities.

7. Rudolph A. Marcus, who is 92, is a Caltech chemist who was awarded the 1992 Nobel Prize “for his contributions to the theory of electron transfer reactions in chemical systems.” The Marcus theory, named for him, describes the rates at which an electron can move or jump from one chemical species to another. Today the Marcus Group at Caltech researches a wide variety of chemical phenomena, including ozone gas formation and semiconductor quantum dots.

But write to me at jason.pontin@technologyreview.com, and tell me your favorite counterexamples to the prevailing youth chauvinism.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.