Got Sleep Problems? Try Tracking Your Rest with Radar.

Radar, often thought of as a tool for tracking missiles and speeding cars, may also be handy as a noninvasive way to monitor sleep.

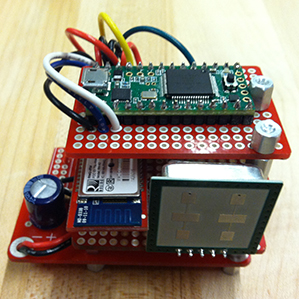

Researchers at Cornell University, the University of Washington, and Michigan State University recently conducted a study in which they used an off-the-shelf radar device to track body movements and heart and breathing rates, sending the data via Bluetooth to a smartphone app to figure out when and how well people are sleeping.

The researchers tested their technology, dubbed DoppleSleep, against EEG and other sleep-logging sensors. They found that it could tell if someone was sleeping or awake nearly 90 percent of the time and judge whether the person was in the deeper REM stage of sleep or non-REM sleep about 80 percent of the time. A paper on the work will be presented in September at the ubiquitous-computing conference UbiComp in Japan.

Beyond its potential for helping healthy people figure out how well (or poorly) they’re sleeping at night, sleep tracking can be used to help signal problems such as sleep disorders. But as with many types of physiological signal tracking, doing it accurately tends to require sensors secured to just the right spots on the body; if you spent the night being studied in a sleep lab, for instance, you’d have a bunch of sensors and electrodes stuck to you to measure things like your brain-wave activity.

While a number of consumer sleep-tracking products are much less invasive, they can still be annoying, requiring you wear a wristband, which may not be very accurate, or place a pad below the mattress and perhaps a sensor by the bed.

Tanzeem Choudhury, an associate professor of information science at Cornell University and a coauthor of the paper, says a big motivation for conducting the work was to determine whether it was possible to get a good measure of sleep without requiring a device that makes contact with the body or the bed.

From what the group has seen so far, she says, “I definitely think you can.”

DoppleSleep operates on the same principle as the radar cops use to catch speeding drivers: its transceiver tracks the phase changes in electromagnetic waves that reflect off the sleeping person, but in this case the information is used to monitor their movements. This data is sent to a smartphone app that uses algorithms to estimate heart and breathing rates, detect changes in position, and determine which of the two main types of sleep a person is experiencing.

The system can also track things like how long it takes you to fall asleep, how long you sleep overall, and how many times you wake up.

Researchers tested DoppleSleep with eight study participants, each of them placing it a couple of feet from their bodies during two sleep sessions. To get a sense of how the system compared with other technology that the researchers considered accurate at tracking sleep, participants wore a biometric-tracking shirt, a sleep-tracking headband, and a wristband.

Choudhury can imagine turning DoppleSleep into a commercial product eventually, though she says it needs more validation in the lab first. The researchers are working on that: Choudhury says they’re planning to use DoppleSleep in some work with a sleep clinic.

One big question remaining is how DoppleSleep will work with multiple people sleeping in the same room. The researchers haven’t yet tested whether they can use the system to monitor more than one person, but Choudhury thinks that could work if they can determine how to place the technology to avoid interference.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.