How to Make Graphene Using Supersonic Buckyballs

Graphene is one of the wonder materials of our age. It is some 200 times stronger than steel, it is an extraordinary conductor of heat and electricity, and it is almost transparent. And yet making graphene is still tricky, particularly when it needs to sit on a substrate for applications such as electronics.

Today, Simone Taioli at the Trento Institute for Fundamental Physics and Applications in Italy and a few pals say they’ve worked out how to do it starting with the famous football-shaped molecule buckminsterfullerene.

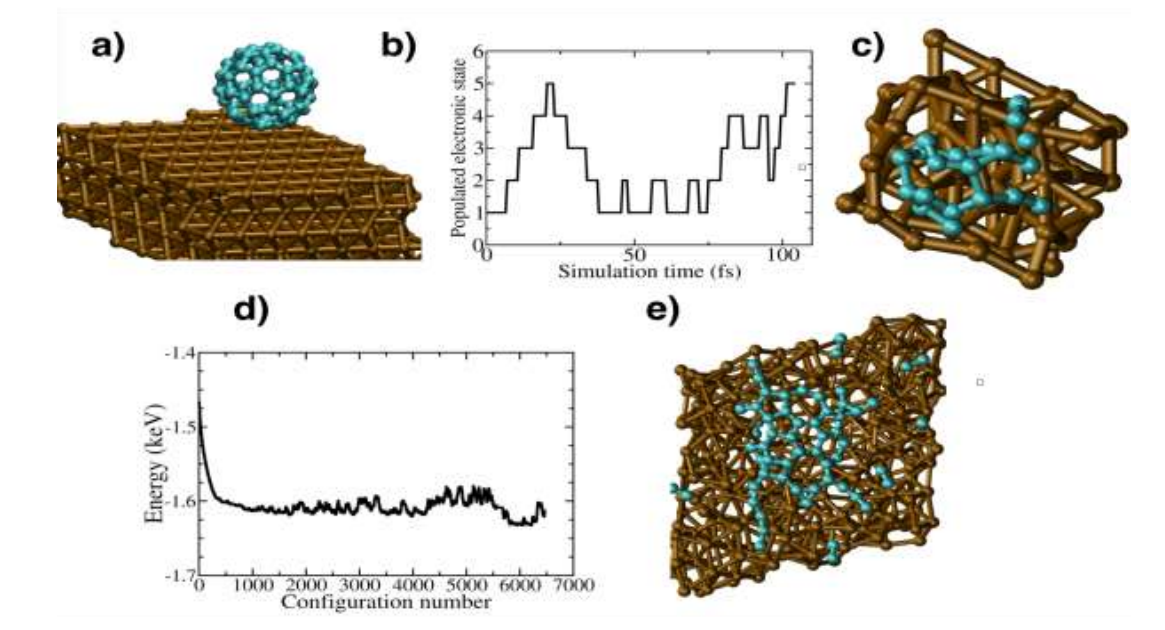

Their idea is remarkably simple: bombard the substrate with buckyballs travelling at supersonic speeds. That’s fast enough to crack them open when they hit, and the resulting unzipped cages then bond together to form a graphene film.

Researchers have long thought of using buckyballs as a precursor for graphene. But the only way to get them to unzip and bind together is to heat them to temperatures in excess of around 600 °C.

That’s not particularly effective, because those high temperatures can change the properties of the substrate, in particular the amount of carbon it adsorbs. That results in irregular films with serious defects.

The new technique gets around these problems. The team accelerates the buckyballs by releasing them into a helium or hydrogen gas, which they allow to expand at supersonic speeds, carrying the carbon balls with it. That gives the buckyballs energies of around 40 keV without changing their internal dynamics (unlike ordinary heating which dramatically increases the molecular vibrations).

These guys then aim the buckyballs at a copper sheet and watch them smash into it like flies onto a windscreen. The result is a fairly even coating of graphene-like material in a single layer.

This material has its own idiosyncrasies. For a start, it is not made of regular hexagons, like perfect graphene. Instead it also contains pentagons, which come from the original buckyball structures. That’s potentially useful because the pentagons could introduce a band gap into the material, something materials scientists have longed hoped to create in graphene.

Although just a proof of principle at this stage, the technique looks interesting, not least because it produces relatively high-quality films and could also be applied to a wide range of other materials such as metals, semiconductors, and insulators. And that could pave the way for a new generation of electronic devices.

Interesting stuff!

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1507.07859 : Towards Room-Temperature Single-Layer Graphene Synthesis By C60 Supersonic Molecular Beam Epitaxy

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.