Teach Your Robot to Do the Dishes

Roomba has a new friend. Researchers have developed a robot that can help clean the kitchen.

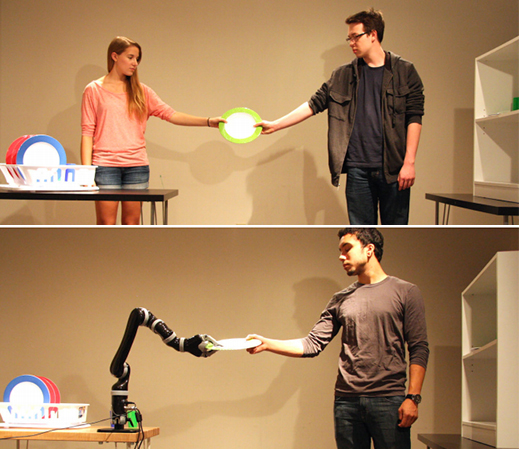

In a paper presented at Robotics Science and Systems in Rome in July, scientists at the University of Wisconsin-Madison describe how they taught a Kinova Mico robot arm to help people do the dishes. The key, apparently, is slowing down and letting human team members take charge. “We want robots to follow our lead, or at least plan their actions with an awareness of ours,” says Bilge Mutlu, associate professor of computer science, psychology, and industrial engineering and an author of the paper.

It’s all about collaboration. The researchers started by getting the robot to watch humans handing each other plates from a drying rack and stacking them on shelves. A Kinect sensor tracked the speed and position of the givers’ and receivers’ arms during the handover. The scenario was then repeated with the receiver working much more slowly, having to solve a short mathematical problem before shelving the plate. This forced the giver to adapt his actions to the receiver’s availability.

The researchers analyzed data from eight human teams, and found that people use a combination of two methods for coping with a sluggish colleague. Some wait until their partner is ready for the next dish, others simply slow down to fill the extra time.

Mutlu installed the robot as giver and, using the Kinect again, monitored its human partners’ performance. The algorithm managed to predict when a user was ready for the next dish with an accuracy of over 90 percent. The researchers then programmed the robot to respond with three different strategies.

Sometimes it would work as fast it could, proactively holding out a dish regardless of whether the person was ready. Sometimes it would wait until the receiver had completely finished with the previous dish before delivering the next. At other times, the robot would mimic human behavior, adaptively tracking its human coworker by slowing or pausing.

Users were then asked to rate each system for awareness, fluency, intelligence, and patience. They much preferred reactive and adaptive robots, with the intuitive adaptive system also working faster (although not as fast as the pushy proactive robot). “There’s a trade-off between team performance and user experience,” notes Mutlu. “Users want to interact with robots at their own pace, as opposed to maximizing efficiency.”

While it’s impressive that a robot could learn to mimic human behavior after watching just a handful of examples, Mutlu cautions that more work is needed: “Moving forward, we’ll want to sample a variety of tasks so that not only can we understand the common elements but also how each task varies.” Mutlu thinks robots will eventually help unload groceries, hand human workers parts for assembly, and even guide patients through physical rehab exercises.

If these results hold, the next generation of industrial and domestic robots should spend less time operating in a blur and more watching, listening, and reacting to their human coworkers. Slow robotics could soon be coming to a kitchen near you.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.