Fixing China’s Coal Problem

When William Latta first came to China, in 2005, he intended to look for companies to acquire for the French power giant Alstom. He wound up creating his own.

“I knew that the environmental market was going to develop,” Latta says. “I believed we could do something about China’s pollution problem, and create a profitable business doing it.”

The company that Latta founded, LP Amina, uses ammonia derivatives called amines to reduce pollution from coal plants’ smokestacks, particularly sulfur oxides and nitrogen oxides. LP Amina joined an array of companies that in the first decade of this century undertook a program critical to the future of the world: cleaning up China’s vast and dirty coal industry.

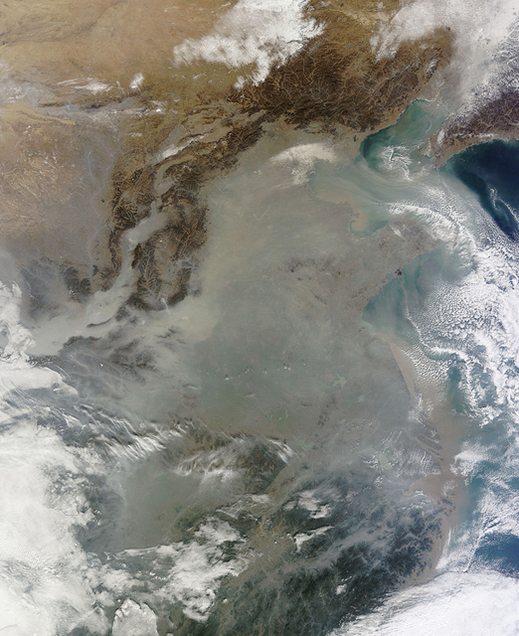

It’s a monumental and urgent task. China is the world’s largest producer and consumer of coal, burning about as much every year as the rest of the world combined. According to a study first published in the medical journal The Lancet, 1.2 million people die prematurely every year from air pollution in China. That’s about the population of Dallas dying every year, mostly because of coal. Air pollution can make big cities like Beijing and Shanghai nearly unlivable, and the giant coal mines of the interior have ravaged thousands of square miles.

That is not news. What’s less understood, at least in the West, is that companies like LP Amina have largely succeeded, and the government’s drive to rein in air pollution from coal plants is making progress. Pollution levels in many of China’s major cities fell from 2013 to 2014, according to Greenpeace, and dropped by nearly another one-third in the first quarter of 2015. Levels of PM 2.5, the deadly particulates that contribute to emphysema and other respiratory diseases, fell by 31 percent in Hebei Province, which includes the Beijing metropolitan area, according to government figures collected by the environmental group. The skies over Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen—the coastal megacities hardest hit by coal smog—are not exactly blue, but they are getting less gray. LP Amina and its competitors are actually becoming victims of their own success. “Our business is definitely slower—we’ll be half the size this year that we were last,” Latta says.

To a large degree, the improvements have come from the government’s crackdown on burning coal for home heating and the closure of small, dirty coal-fired plants close to major cities. They’re also due to the widespread deployment of scrubbers and other antipollution technology that has long been standard in the West. According to some estimates, close to 90 percent of the coal plants in China now have basic pollution controls. “On the conventional pollutants in flue gas, by 2020 the level of compliance in China will be equal to the U.S. or Europe,” says Latta.

That’s a major environmental achievement, and one that has not received enough attention in the Western press. But it leaves behind a deeper challenge: greenhouse gases, which are unaffected by scrubbers and other widely available pollution-control technologies. If you think of everything that has happened until about 2013 as phase 1 of China’s great coal cleanup, then we are now in phase 2: the conversion of coal into synthetic natural gas, or syngas. Continuing to reduce pollution will require the country to take tricky steps, such as implementing carbon capture and significantly reducing the use of coal.

“The big question now is, what happens on CO2?” asks Latta.

Coal-to-gas boom

The significance of that question becomes apparent when you tour the coal industry in Shanxi Province, in northern China near the border with Inner Mongolia, as I did in 2014 while researching my book Coal Wars. There, below ridgelines traced by remnants of the Great Wall, hundreds of small, dirty coal mines still supply gigantic coal-fired plants that belch millions of tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere every year. The central government’s program to shut down coal plants in the east, near the coast, has done little about those in the interior. In fact, the coal industry in the west and north is set for dramatic expansion over the next decade, according to the most recent five-year plan.

In China’s coal cleanup, the years from the early 2000s to around 2012 were the period of desulfurization—limiting release of conventional pollutants and PM 2.5, the stuff that kills people directly. We are now in the age of gasification.

That refers to the process of turning solid coal into syngas, which is made up of hydrogen, carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide. Syngas can be burned to produce electricity or converted into petrochemicals. What’s promising from an environmental standpoint is that the carbon can be captured and removed before the gas is processed, although syngas plants generally don’t do this now.

It’s not a new technology—cut off from oil supplies in World War II, the Nazis made liquid fuel from coal via syngas to keep their jeeps and tanks running—but gasification is now seen as the immediate path forward for China’s beleaguered coal industry. The government has announced plans for dozens of coal gasification plants across Inner Mongolia and Shanxi and Xinjiang Provinces; they are expected to supply liquid fuel for vehicles, ethylene for petrochemical plants, and other products. According to the National Energy Administration, production will reach 50 billion cubic meters of syngas a year by 2020. That would be 25 times more than 2014 production.

Government support, along with rising demand for syngas derivatives, drove a land rush starting in 2005 as big state-owned enterprises broke ground on expansive and hastily conceived coal-to-gas plants. That initial boom was an “epic failure,” according to Bobby Wang, the product marketing leader for gasification at GE Power & Water in China. The early plants were unable to compete with products made from cheap natural gas in the Middle East.

The frenzy has given way to a more measured approach. Now Chinese energy companies, including the major coal suppliers, have formed joint ventures with GE and smaller U.S. companies, such as LP Amina, Synthesis Energy Systems, and Summit Power, to build financially viable plants intended to supply syngas for power generation, petrochemicals, heat for industrial processes, and more. Eventually the boilers to produce electricity in these plants will use integrated gasification combined-cycle (IGCC) technology, the most efficient way to gasify and burn coal. Once these state-of-the-art gasifiers are “unlocking the hydrocarbons” from mineral coal, says Jason Crew, CEO of Seattle-based Summit Power, “you can do all sorts of things, including clean up the carbon.”

However, many of the coal-to-gas plants to be strung across China’s arid northern and western provinces would burn lignite, the low-quality “brown” coal that’s abundant across China and Southeast Asia—which to environmentalists is the sort of dirty, low-energy fuel we should be leaving in the ground. And the environmental benefits of coal gasification are in dispute: according to a report from Greenpeace, which looked at the full life cycle of gasification from mining to end use, China’s coal-to-gas program could add millions of tons of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere over the next decade, putting the carbon-reduction goals detailed in the November 2014 climate-change agreement between Barack Obama and Chinese president Xi Jinping far out of reach.

Nevertheless, a raft of well-funded binational R&D and demonstration projects are seeking to make coal-to-gas plants spew less carbon.

One of these projects is planned not for Inner Mongolia but for the West Texas oil patch. Supported by a $450 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Clean Coal Power Initiative, the Texas Clean Energy Project would combine a 400-megawatt IGCC plant with a facility that produces urea for fertilizer, plus a carbon-capture system that would remove 90 percent of the carbon dioxide produced (about two million tons a year) and use it for enhanced oil recovery in the oil wells of the Permian Basin. Along with Summit Power, the participating companies include Siemens, CH2M Hill, and an engineering and construction unit of the state-owned energy giant China National Petroleum Corporation. Projected to cost more than $1.7 billion, the Texas project would be the most advanced coal plant ever built.

“The novelty in what we’re doing is that the CO2 capture is a by-product of the process—essentially you do it for free,” says Latta.

That’s a rosy scenario, and it’s probably still decades away. The fact is that most carbon-capture projects for coal plants have stalled or been abandoned. GreenGen, a vaunted IGCC prototype in Tianjin that was envisioned as the country’s first large-scale carbon-capture plant, has been beset by multiple delays over its 10-year history and was recently scaled back. Even if the Texas project succeeds, it will be a viable model in only a few locations where there’s demand for the captured carbon. And at the earliest, the prototype plant will not be completed until 2018. Ultimately, the likeliest way for China to continue its progress on pollution control may be simply to burn less coal.

Surprising swing

In the United States, the share of power generated from coal has dropped below 40 percent and is likely to keep going down because cheap natural gas is so abundant. The prospect of a similar reduction in China seemed, until recently, remote.

Remarkably, thanks to a slowing economy, a shift toward lighter, less energy-intensive industries, and a crackdown on small, unlicensed coal burners, coal consumption in China fell nearly 2 percent in 2014, according the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, even as the economy grew by 7.4 percent—the first such drop in decades. A Greenpeace report released in May found that coal consumption fell 8 percent in the first four months of 2015 compared with the same period a year before. If that trend continues for the full year, it would represent “the largest recorded year-on-year reduction in coal use and CO2 in any country.” As the U.S. shale gas revolution shows, dramatic swings in energy consumption can happen suddenly and unexpectedly. Pouring billions into expensive, futuristic clean coal plants may wind up looking, to future energy historians, like throwing good money after bad.

“The argument that the coal industry always tries to make is to paint a picture where coal is critical for economic growth,” says Bruce Nilles, program director for the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign. “They used to say that about the United States, and now things are moving rapidly in the other direction. Now their last gasp is to try and create a sense of inevitability that coal is going to be burned for another 50 years in developing countries like China. But it’s based on false premises.”

This story was updated on July 24 to correct an estimate of the amount of land that has been affected by coal mining and coal-fired power generation in China. It now reads “thousands of square miles” rather than “millions.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.