Supermarkets, Startup Style

The way Americans eat is in flux. Some research suggests that after a long trend of trading home-cooked meals for takeout and restaurant fare, Americans may be returning to their kitchens and choosing more nutritious food.

Shopping for food is changing too, and new technology-fueled models are emerging to serve this new style of eating, though they still account for just a small fraction of total food sales. Straightforward websites and apps that make it easy to plan and shop for meals are challenging supermarkets to rethink how they sell food.

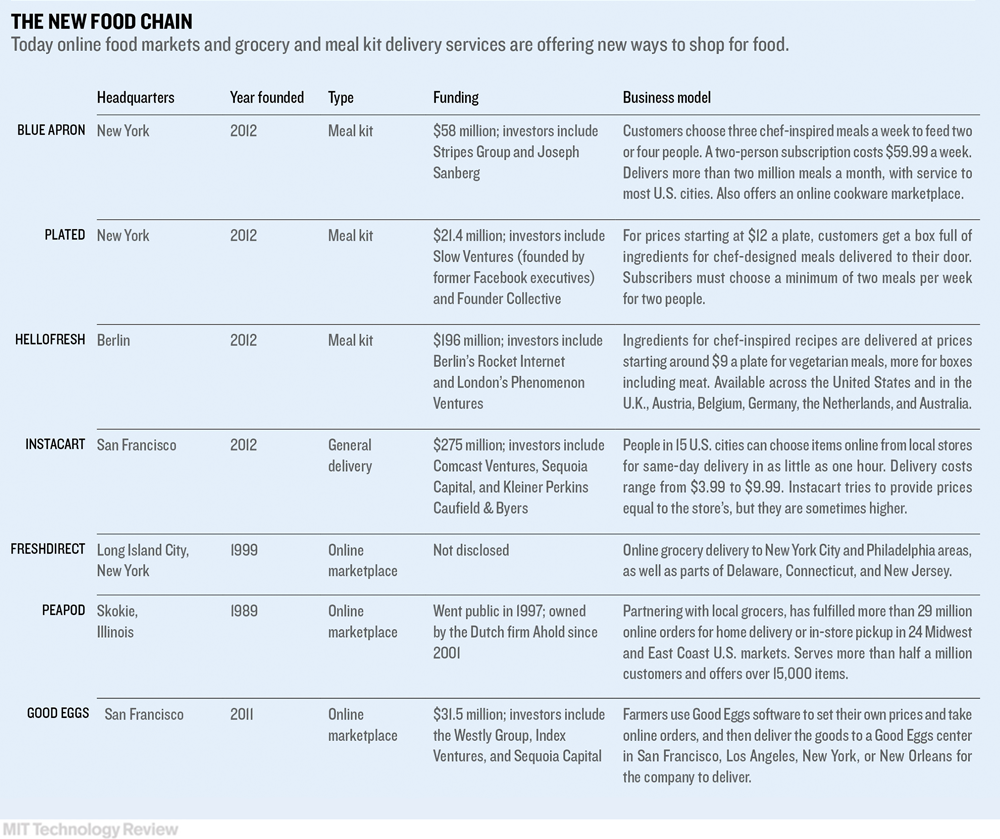

Meal-preparation sites like Plated, HelloFresh, and Blue Apron have gained millions in venture capital. They offer websites that feature recipes designed by chefs, and then they deliver exactly the ingredients needed to make them in a refrigerated box to a customer’s doorstep each week. HelloFresh and Blue Apron both say they are delivering more than one million meals per month to subscribers, who typically receive at least three meals per week.

Convenience comes at a price. At Blue Apron, each individual portion for a two-person plan starts at $9.99; at Plated, a “plate” starts at $12.

Instacart, which delivers food from local grocery stores in 15 U.S. cities, charges anywhere from $3.99 to $9.99 plus the cost of the food, depending on how big the order is and how quickly the customer wants it delivered.

“It’s been great but expensive,” says Rence Delino, a frequent Instacart customer in Washington, D.C. He likes that he usually receives deliveries within an hour and a half from any grocery store in the area (deliveries at the cheapest price usually come within two hours, but shoppers can pay more for service within an hour), and he appreciates the cheerful personal shoppers who call to confirm any replacement items they’ll pick up if something on the shopping list is out of stock.

Delino opted for a $99 membership that allows frequent shoppers to get free deliveries for a year on orders of more than $35. But some items cost significantly more when he orders them through Instacart than they would if he bought them himself. One is English muffins, which carry a regular price tag of $4.29 at his local store (in-store promotions can bring them as low as 99 cents per pack) but have cost more than $5 when purchased through the app, he says.

The company says it tries to keep prices on the app the same as in the store, thanks to partnerships with more than 60 retailers. But some grocers’ online prices may differ from prices in store. Instacart recently changed its interface to make its pricing more transparent.

Facing this new trend, some supermarkets are testing out technologies that similarly help get customized food orders delivered quickly. When home chefs find a recipe they’d like to try on the free recipe discovery app and website Yummly, they can export the shopping list to Instacart and arrange a delivery from a local store. Meanwhile, the online grocery store Peapod has started delivering recipe ingredients for the meal-planning site Gatheredtable.

Supermarkets are also looking for ways technology can improve shopping in stores, which is how most Americans still buy their food. Indiana-based Marsh Supermarkets has teamed with marketing company inMarket to install beacons at its 77 stores. Shoppers can see a layout of their favorite store through a smartphone app. When they add an item to their shopping list, that item appears on the map. Beacons can send location-appropriate promotions to shoppers’ phones.

In the future, the chain plans to experiment with apps for the Apple Watch, among them a notification from a beacon in the store to alert you if you are nearing the checkout counter without having crossed an item off your in-app shopping list.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.