The Database for Individuals Who Have Transcended Linguistic, Temporal, and Geographic Boundaries

Various organizations and individuals have attempted to list the most important people in history. These rankings are notoriously difficult to justify because they are often biased by language, geography, gender, and so on.

That’s not just a problem for list collectors. Social scientists are also interested in these kinds of rankings because they provide insight into the way humans transmit nongenetic information from one generation to the next. This information includes science, literature, and other works of art but also beliefs, tastes, expectations, and so on.

The systematic study of this kind cultural production has the potential to revolutionize our understanding of humanity. But the lack of good databases to base this work on is something of a drawback.

Today, Amy Zhao Yu and co at MIT’s Media Lab attempt to transcend these limitations by creating a list with cultural input from almost every country and from over 280 languages.

They call this new database “Pantheon 1.0: a manually curated dataset of individuals that have transcended linguistic, temporal, and geographic boundaries.” And they expect it to kick-start the study of culture with the same kind of data mining techniques that are revolutionizing other areas of sociology and anthropology.

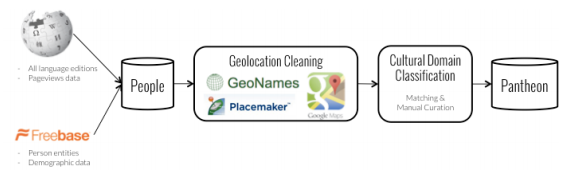

Their approach is straightforward. These guys download over 11,000 biographies from the online data repository Freebase and link them to their pages in 277 language versions of Wikipedia.

They then create a list of occupations subdivided by cultural domain. For example, the occupation ‘magician’ is a type of media personality in the category of public figure.

Next, they allocate a single occupation to each person on the list, even if they might be known for more than one thing. “For example, Barack Obama is a politician (although he is also listed as a writer on Freebase), and Shaquille O’Neal is a basketball player (although he is also listed as an actor on Freebase),” say Yu and co. “The challenge of fairly distributing the cultural impact of polymaths will be left for future consideration.”

Having created this database, the next question is how to rank the individuals on it. Yu and co do this in two ways. The first is simply to count the number of Wikipedia language editions that have an article about that person. The thinking is that this is an indication of the extent to which this person’s impact has been felt across cultural boundaries.

Yu and co call the second method the Historical Popularity Index. For this they take the number of Wikipedia language-mentions and adjust it for factors such as the number of page views, the concentration of page views in different languages and the number of non-English page views as well as the time since that person was born.

That produces some interesting rankings. Of people born before 500 AD, the person with the most Wikipedia language mentions is Jesus, followed by Confucius. However, the two people who head the Historical Popularity Index are Aristotle and Plato.

For the most recent period—1900 to 1950—the person mentioned in the most Wikipedia language versions is the Brazilian singer Hebe Camargo while the Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara tops the Historical Popularity Index. Adolf Hitler tops the previous period of 1850 to 1899 on both counts (the period refers to birthdates).

Others who head the lists from the period in which they lived include: Muhammad, Leonardo Da Vinci, Isaac Newton, William Shakespeare, and Mozart.

Yu and co are quick to point out the biases in their database. For example, using data from Wikipedia introduces an important bias because Wikipedia editors are not a representative sample of the world population. And using biographies as a proxy for cultural production only works when there is a clear link between an individual and a specific piece of cultural expression but otherwise tends to exclude group efforts.

That’s an interesting piece of work that produces many potential talking points—these kinds of rankings are always fascinating to pore over. And it opens up the possibility of studying the evolution of cultural production and how this kind of nongenetic information has swept through different parts of the world at different times.

It may not be perfect but it is an interesting first step toward a new kind of data-based science.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1502.07310 : Pantheon: A Dataset for the Study of Global Cultural Production

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.