Computational Anthropology Reveals How the Most Important People in History Vary by Culture

The study of differences between cultures has been revolutionized by the internet and the behavior of individuals online. Indeed, this phenomenon is behind the birth of the new science of computational anthropology.

One particularly fruitful window into the souls of different cultures is Wikipedia, the crowd-sourced online encyclopedia with over 31 million articles in 285 different languages. One important category consists of articles about significant people. And not just anyone can appear. Wikipedia has specific criteria that notable people must meet to merit inclusion.

So an interesting question is how the most important people vary from one language version of Wikipedia to another. Clearly, these differences must arise from the cultural forces that determine notability (or notoriety) in different parts of the world.

Today, Peter Gloor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge and a few pals say they have calculated the most significant people in four different language versions of Wikipedia—English, German, Chinese and Japanese. And they say important differences emerge, not just in the names that appear, but in the broader make-up of the lists.

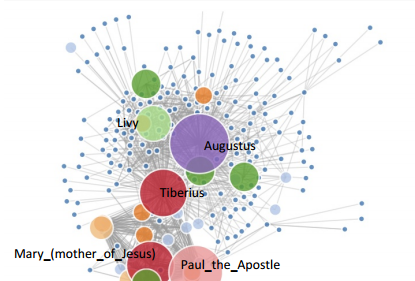

The team’s goal is to create a social network of all the people that appear in a given language version of Wikipedia. They start by downloading the articles for all prominent people—a total of 800,000 in the English language version, for example.

They next extract the birth and death dates and work out which people were alive at the same time. They then examine the links on each page to determine who points to whom. This allows Gloor and co to draw up a network of links between people who lived at the same time for each year between 3000 BC and 1950.

For example, the most significant people in the year 0 include the Greek historian and biographer Plutarch who is linked to contemporaries such Hadrian, Caesar and Nero. However, links from Plutarch’s page to people who lived before or after him are ignored.

Finally, Gloor and co rank the people in these networks by importance using the famous Pagerank algorithm. This is the same algorithm that Google uses to rank pages on its search pages. It works by ranking entries more highly if they are pointed to by other entries that also rank highly.

The resulting lists make for interesting reading. The longer versions contain 50 entries but even the first few entries reveal some interesting differences between the different language versions.

The top five in the English language version are George W Bush, William Shakespeare, the Victorian biographer Sidney Lee, Jesus and Charles II of England.

The top five in German are: Adolf Hitler, Johan Goethe, Aristotle, Pope Benedict XVI and Plato.

In the Chinese version they are: Mao Zedong, the early 20th century emperor and general Yuan Shikai, the Taiwanese singer Jay Chou, the 16th-century samurai warrior Oda Nobunaga and the 16th century Japanese ruler Tokugawa Ieyasu.

And in Japanese: the 20th century biographer Ikuhiko Hata, the 16th century Japanese ruler Tokugawa Ieyasu, the 16th century Japanese warrior Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Adolf Hitler and the 16th-century samurai warrior Oda Nobunaga Oda Nobunaga.

These lists reveal the most important people of all time in these cultures, say Gloor and co. There are several notable features that distinguish east from west. For example, the top 50 from the Japanese version contains only warriors and politicians as does the top 10 from the Chinese version. By contrast, about half the top ten and top 50 are scientists, artists or religious leaders in the western versions.

Just as striking is the prevalence of figures from elsewhere in the world. Non-English leaders make up 80 percent of the entries in the English language list. By contrast, only a handful of non-Chinese leaders appear in the Chinese language version.

One artefact of the way these lists are compiled is the role of historians. The biographers Sidney Lee and Ikuhiko Hata are both prominent because of the links from their pages to contemporaries who they have written about. That clearly gives them an inflated importance on this ranking.

Nevertheless, the rankings provide an interesting insight into the forces that shape the cultural sense of importance around the world. “Probing the historical perspective of many different language-specific Wikipedias gives an X-ray view deep into the historical foundations of cultural understanding of different countries,” say Gloor and co.

Fascinating work and there’s clearly more gold to be mined from the increasingly rich cultural ore on Wikipedia.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1502.05256 : Cultural Anthropology Through the Lens of Wikipedia - A Comparison of Historical Leadership Networks in the English, Chinese, Japanese and German Wikipedia

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.