How Computer Scientists Solved The Challenge of Zero-Maintenance Data Storage

The cost of hard drive data storage has fallen dramatically in recent years. In 2008, this kind of memory cost around $0.11 per gigabyte. Today it costs around $0.04 and prices continue to drop. That’s having a significant impact on the way storage centres view their costs because the price of replacing disks when they fail is increasingly dominated by the cost of the service call itself.

Today, Jehan-François Pâris at the University of Houston in Texas and a few pals say they have developed a way to eliminate the cost of service calls by creating data storage that is so reliable that it would not require any human intervention throughout its whole lifetime.

Their trick for making zero maintenance data storage is to include enough spare discs to take on the data from any that fail. “We propose to reduce the maintenance cost of disks arrays by building self-repairing arrays that contain enough spare disks to operate without any human intervention during their whole lifetime,” they say. And the team has simulated the behaviour of such a system and say it outperforms current data redundancy systems.

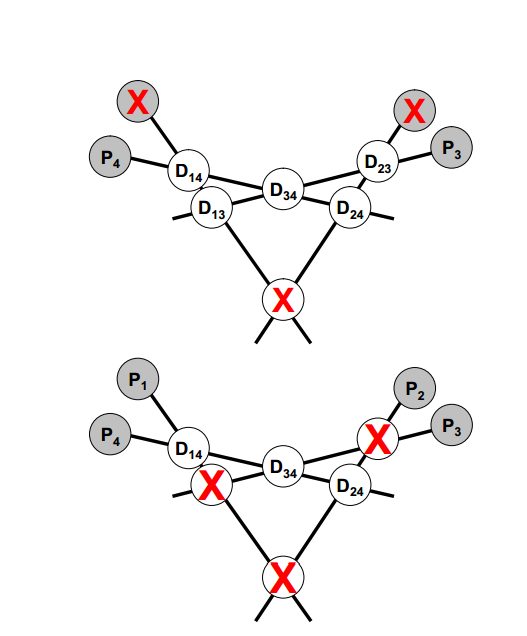

The most commonly used data storage technology is called RAID (redundant array of independent disks). The most advanced incarnation, called level 6, consists of a set of data discs that are constantly checked against a smaller set of parity discs. That ensures that the data is redundant and can be recreated should the discs fail.

For example, a standard RAID architecture uses 4 parity discs to protect the contents of 6 data discs against all failures of up to 2 discs. Any new system would have to perform better than this.

Pâris and co have simulated the reliability of a memory system in which both parity discs and spare discs are included. The challenge is to achieve 99.999 percent reliability but with a reasonable increase in the amount of space needed to house spare discs (clearly, no datacentre could house an infinite number of spare discs).

The team had to make a number of assumptions about the reliability of discs in running the simulation. They make these assumptions based on the performance of 25,000 discs and their failure rates studied by the data storage company Backblaze.

This suggests that discs have a relatively high failure rate during the first 18 months, a much lower rate during the next 18 months and a high rate after that. They also assume that a disc repair takes 24 hours, given a disc transfer rate of around 200 MB/s.

Curiously, the simulations show that bigger is not necessarily better. They indicate that the best arrangement occurs when there are 45 data discs, 10 parity discs and 33 or 34 spare discs. This gives the best compromise between the extra space and the 99.99 percent reliability.

In fact, when the number of data discs is much larger than this, the system can never achieve 99.999 percent reliability because of the time it takes to recover data when a disk fails. Larger systems have a greater chance of another disk failing. And if that happens during the recovery period, the system can never catch up, even if it has an infinite number of spare discs.

The team go on to compare this performance with the standard RAID level 6 architecture and show that it is significantly better.

That is an interesting new take on storage reliability that could make data storage not just more reliable, but cheaper too. And with the price of magnetic storage set to fall even further, the importance of taking human interventions out of the loop is only likely to increase.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1501.00513 : Self-Repairing Disk Arrays

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.