Best of 2014: The Revolutionary Technique That Quietly Changed Machine Vision Forever

In space exploration, there is the Google Lunar X Prize for placing a rover on the lunar surface. In medicine, there is the Qualcomm Tricorder X Prize for developing a Star Trek-like device for diagnosing disease. There is even an incipient Artificial Intelligence X Prize for developing an AI system capable of delivering a captivating TED talk.

In the world of machine vision, the equivalent goal is to win the ImageNet Large-Scale Visual Recognition Challenge. This is a competition that has run every year since 2010 to evaluate image recognition algorithms. (It is designed to follow-on from a similar project called PASCAL VOC which ran from 2005 until 2012).

Contestants in this competition have two simple tasks. Presented with an image of some kind, the first task is to decide whether it contains a particular type of object or not. For example, a contestant might decide that there are cars in this image but no tigers. The second task is to find a particular object and draw a box around it. For example, a contestant might decide that there is a screwdriver at a certain position with a width of 50 pixels and a height of 30 pixels.

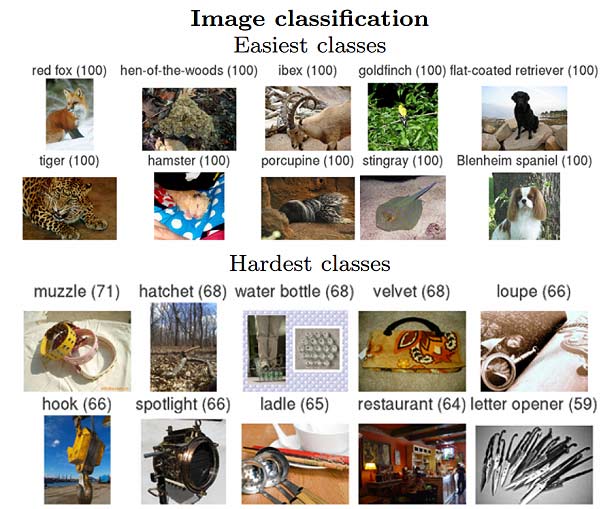

Oh, and one other thing: there are 1,000 different categories of objects ranging from abacus to zucchini, and contestants have to scour a database of over 1 million images to find every instance of each object. Tricky!

Computers have always had trouble identifying objects in real images so it is not hard to believe that the winners of these competitions have always performed poorly compared to humans.

But all that changed in 2012 when a team from the University of Toronto in Canada entered an algorithm called SuperVision, which swept the floor with the opposition.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.