A Whirlwind Tour of Europe Before the War

On the evening of June 9, 1933, nine MIT students and three professors—one from MIT and two from the University of New Hampshire—set sail for Europe on the S.S. Statendam out of Hoboken, New Jersey.

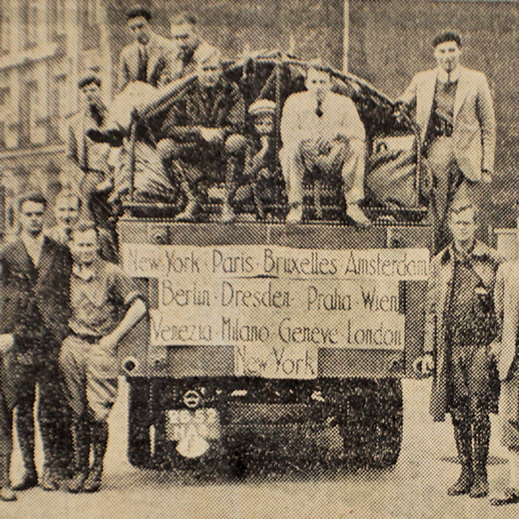

It was the start of the first European tour of industry for students in MIT’s Department of Business and Engineering Administration. Department head Edwin Schell organized the trip to give students a taste of real-world management practices at various manufacturing plants and businesses across the continent. On the agenda: cars, glassware, champagne, diesel engines, chocolate, electrical supplies, beer, nuts and bolts, cameras, medical equipment, pottery, railway cars, cigars, newspapers, radios, and more. And to see it all, the group brought along a bus that would double as kitchen and campsite throughout the seven-week, nine-country journey.

MIT launched its program in business administration (Course 15) in 1914 to satisfy a growing interest among students in the business side of engineering. Schell joined the program’s faculty in 1917 and became department head in 1930. The following year, he organized the first of two tours of American industry that would serve as models for the 1933 summer trip to Europe.

The students enjoyed seven days of shipboard games, movies, and dancing while Schell traveled ahead to arrange industry visits. Upon docking in France, they piled onto the bus, drove about 70 miles, and camped in an orchard for the night.

In an article from August of that year, a journalist for the Boston Herald explained what would become the group’s nightly routine:

“The top [of the bus] was expanded until it became a huge tent. Rods were attached to its sides, and tiers of bunks materialized. Blanket rolls and camp chairs were brought out. A gasoline stove was set up, and the tailboard of the [bus] descended and became a dining table. A delegation of the boys went out for provisions, others went for water, and the whole ménage took on the semblance of a military camp.”

As for the cooking, “Well, it was all right—nothing to kick about,” one of the students told the journalist.

The students spent their second night in a factory yard outside Paris, where they had their first industry visit—with a machine gun manufacturer.

In the weeks to come, they’d relocate to the barn of a champagne factory, a park next to the Belgian king’s summer palace, the 1928 Olympic Stadium in Amsterdam, the banks of the Rhine River in Germany, the court of a police station in Austria, a farm in Canterbury, sites next to a filling station in Munich and 5,000 feet above sea level in the Swiss Alps, and various fields and public commons around Europe.

Nearly everywhere they went, locals gathered to watch the students transform their bus or play a game of baseball. Young French boys took a particular interest in their shaving habits.

Likewise, the MIT students noted the various cultural quirks—Europeans’ preference for hard-crusted bread, their unfamiliarity with “cutting in” at dances, their more generous tipping habits, and the difficulty of finding good, cheap cigarettes.

In Germany, the students faced Nazi propaganda. One of them recalled getting reprimanded when he stumbled upon a Nazi parade and failed to take his hands out of his pockets as a swastika passed.

At the end of the seven weeks, the students compiled a report detailing their daily activities and made recommendations for future trips. Among them: eat in restaurants less often and outfit the bus with some kind of rope to keep crowds at bay. Overall, they declared, the tour was a success both academically and culturally.

The department offered the same trip every summer after that through 1939, when World War II broke out in Europe. Schell had hoped the trips would resume after the war, but they never did.

The Department of Business and Engineering Administration eventually morphed into the Alfred P. Sloan School of Management. Even today, real-world experience remains central to its curriculum—Sloan students travel all over the world studying local businesses and industries.

“[Sloan] has a history of a lot of project-based experiential learning in very real-world environments,” says Dean David Schmittlein. “And it also has a history of having people engage globally, and happily we have a number of courses where those two things come together.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.