Steve Jobs Lives on at the Patent Office

What is Steve Jobs’s legacy? Here’s one measure: since his death in 2011 from pancreatic cancer, the former Apple CEO has won 141 patents. That’s more than most inventors win during their lifetimes.

Jobs was closely involved in the details of many Apple products, and some of his inventions are still working their way through the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. The large number of them reflect Apple’s intense efforts to patent every aspect of its products, no matter how small, something Jobs himself encouraged.

Altogether, a third of the 458 patented inventions and designs credited to Jobs have been approved since he died.

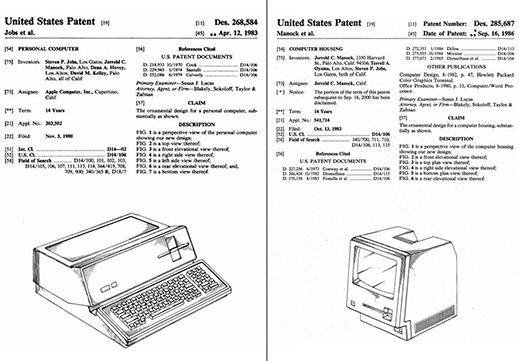

Jobs’s patent documents are a record of Apple’s history from startup to one of the world’s largest companies. His first patent, won in 1983, is titled simply “Personal Computer.” One of the newest, filed after his death and approved in August, covers the design of the dramatic glass cube that’s the entrance to Apple’s store on Fifth Avenue, in Manhattan.

Some Apple watchers have questioned if Apple can succeed without its iconic founder. Its current CEO, Tim Cook, is a pragmatic supply chain specialist who rose through the company making sure Chinese factories delivered iPhones on time. Cook’s name has never appeared on any patent.

Earlier this year, journalist Yukari Iwatani Kane, in her book Haunted Empire: Apple After Steve Jobs, made the case that Apple would stall and fade from importance without Jobs. She argued that Apple, like Polaroid after Edwin Land, or Sony after Akio Morita, would not succeed without the temperamental genius who created “amazing” products.

But Apple has not yet slowed down. It has announced promising new products like the Apple Watch and a payment system, Apple Pay. And Apple’s sales keep increasing—annual revenue has more than doubled to $182 billion, since Cook took the reins.

As Apple succeeds under a different leader, one thing that could get reassessed is the importance of Jobs’s inventions.

In 2012, Jobs was posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. He even has his own traveling museum show, “Patents and Trademarks of Steve Jobs: Art and Technology that Changed the World,” most recently appearing at Denver’s public library.

But Jobs’s many patents “don’t make him one of the greatest American inventors in history,” says Florian Mueller, a programmer and patent consultant in Germany who has closely followed litigation around the iPhone. He notes that many of Jobs’s patents are on designs—like the look and feel of the iPhone—not on more substantial technical advances.

“Whether Steve Jobs was a great inventor depends on whether one is prepared to define the term extremely broadly,” says Mueller. “I’m convinced that if true American inventors like Edison, Bell, and Whitney looked upon Steve Jobs’s achievements and contributions, they would undoubtedly respect the man for what he’s done but they wouldn’t consider him one of their own.”

One criticism is that on his patents, Jobs’s name often appears alongside a score of others, meaning these inventions or designs weren’t entirely of Jobs’s making. Instead, Jobs shared credit for what Apple’s more than 80,000 employees did, something Kane argues “fed into his legend as a one-in-a-lifetime visionary.”

Tim Wasko, who developed the interface for Apple’s QuickTime player and the iPod, remembers that Jobs would give feedback on small details, and he’d often end up with a position on a patent. That’s what Wasko says happened when he came up with a concept for a button used on software called iDVD. The button shuts like an iris, giving you a chance to interrupt a process. “It looked pretty cool so he loved that,” says Wasko. “He had useful comments, suggestions, and it’s worthy of him being on the patent.”

Deceased inventors can win patents if the approval process draws out, or when attorneys seek “continuations”—essentially new versions of old patents. And the more lawyers and money an inventor has, the more likely his ghost will rattle on. The estate of Jerome Lemelson, the sometimes-controversial independent inventor who came up with the bar code reader, received 96 patents following his death in 1997 at age 74.

Who is named on a patent is sometimes just as important as what it says. At least that’s true for Jobs. In 2012, during a lawsuit with Motorola and Google, a Chicago judge had to order Apple’s lawyers to stop referring to a key patent covering swiping and scrolling on touch screens as “the Steve Jobs patent.” Her reasoning: Apple’s lawyers were trying to turn the case into a popularity contest by invoking the beloved Apple founder. (Jobs was the first of 25 inventors named on that patent.)

Even as Jobs became ill, Apple’s lawyers kept filing patents in his name every few days, including one for a variation of the Mac’s scrolling toolbar on October 4, 2011, the day before he passed away.

And Jobs’s name is still getting added to new patents, some of which offer a window on his personal interests, like a 260-foot super yacht, Venus, that he commissioned and helped design. Only this March, a company based on Cape Cod, Savant Systems, listed Jobs as the lead inventor on a patent application covering the idea of using a tablet like the iPad to steer a sea vessel.

Deep Dive

Computing

How ASML took over the chipmaking chessboard

MIT Technology Review sat down with outgoing CTO Martin van den Brink to talk about the company’s rise to dominance and the life and death of Moore’s Law.

How Wi-Fi sensing became usable tech

After a decade of obscurity, the technology is being used to track people’s movements.

Why it’s so hard for China’s chip industry to become self-sufficient

Chip companies from the US and China are developing new materials to reduce reliance on a Japanese monopoly. It won’t be easy.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.