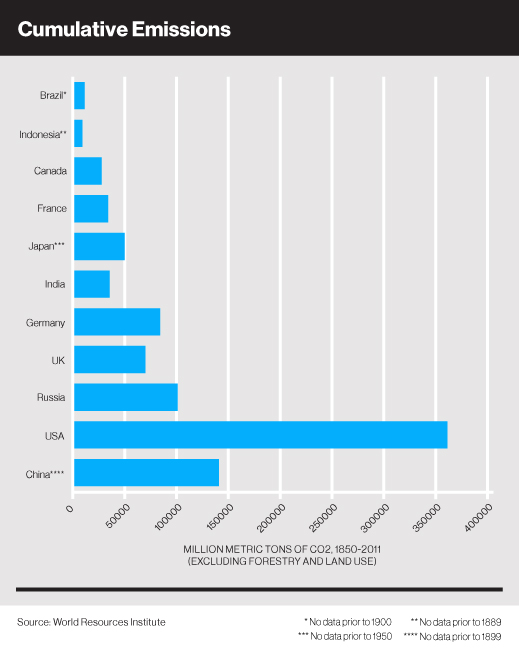

The United States Is Far and Away the Leader in Carbon Dioxide Emissions

The newly published synthesis of the Fifth Assessment Report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is yet another reminder that to maintain a legitimate shot at avoiding warming of greater than 2 °C, greenhouse-gas emissions must be cut 40 to 70 percent by midcentury and reduced to zero by 2100.

How exactly to achieve this is the subject of ongoing geopolitical debate. The United States points to its annual emissions, which have been gradually trending downward, and argues that China, now the world’s leading annual emitter, bears equal responsibility, along with other high-emitting nations like India. China, meanwhile, argues that because the U.S. and other wealthy nations have contributed a disproportionate share of the greenhouse gases already accumulated in the atmosphere, they should be held more accountable for emissions cuts over the next several decades.

Since the effects of atmospheric carbon dioxide linger for centuries (See “Climate Change: The Moral Choices”), that’s a fair point. In the fifth assessment report, the IPCC has for the first time embraced the concept of a carbon budget. According to the panel, ensuring that warming remains below 2 °C will require keeping the total of human-caused emissions, from the beginning of the industrial era through the end of this century, below about a trillion tons of carbon. Over half of that total had already been emitted into the atmosphere by 2011.

undefined

At the very least, an accounting of cumulative historical emissions by individual countries is relevant context for today’s geopolitical gridlock. For example, according to the World Resources Institute, the United States has emitted some 10 times as much as India, whose population is nearly four times larger.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.