How Wikipedia Data Is Revolutionizing Flu Forecasting

This time last year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta launched a competition to find the best way to forecast the characteristics of the 2013-2014 influenza season using data gathered from the internet. Today, Kyle Hickmann from Los Alamos National Laboratories in New Mexico and a few pals reveal the results of their model which used real-time data from Wikipedia to forecast the ground truth data gathered by the CDC that surfaces about two weeks later.

They say their model has the potential to transform flu forecasting from a black art to a modern science as well-founded as weather forecasting.

Flu takes between 3,000 and 49,000 lives each year in the U.S. so an accurate forecast can have a significant impact on the way society prepares for the epidemic. The current method of monitoring flu outbreaks is somewhat antiquated. It relies on a voluntary system in which public health officials report the percentage of patients they see each week with influenza-like illnesses. This is defined as the percentage of people with a temperature higher than 100 degrees, a cough and no other explanation other than flu.

These numbers give a sense of the incidence of flu at any instant but the accuracy is clearly limited. They do not, for example, account for people with flu who do not seek treatment or people with flu-like symptoms who seek treatment but do not have flu.

There is another significant problem. The network that reports this data is relatively slow. It takes about two weeks for the numbers to filter through the system so the data is always weeks old.

That’s why the CDC is interested in finding new ways to monitor the spread of flu in real time. Google, in particular, has used the number of searches for flu and flu-like symptoms to forecast flu in various parts of the world. That approach has had considerable success but also some puzzling failures. One problem, however, is that Google does not make its data freely available and this lack of transparency is a potential source of trouble for this kind of research.

So Hickmann and co have turned to Wikipedia. Their idea is that the variation in numbers of people accessing articles about flu is an indicator of the spread of the disease. And since Wikipedia makes this data freely available to any interested party, it is an entirely transparent source that is likely to be available for the foreseeable future.

Hickman and co use the flu-article data from earlier years to train a machine learning algorithm to spot the link with the influenza-like illness figures collected by the CDC. They then used the algorithm to predict flu levels in real time during last year’s flu season.

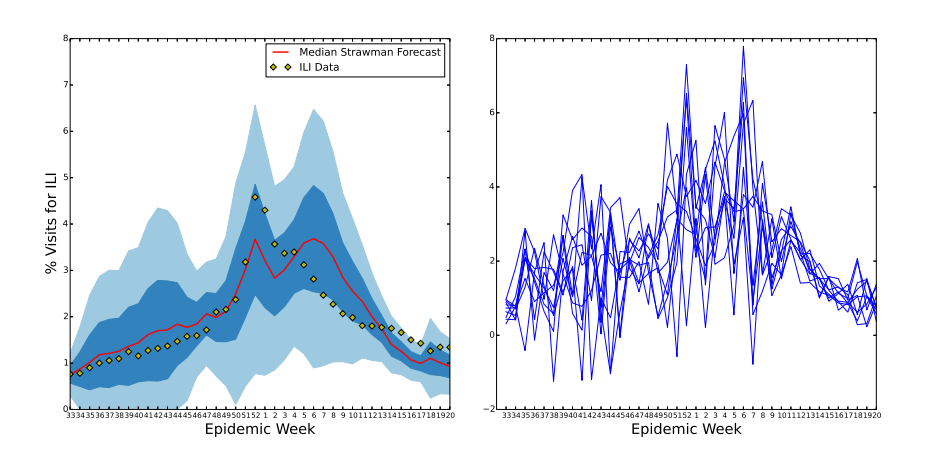

The results are a good predictor of the ground truth data that the CDC makes available two weeks later. “Wikipedia article access logs are shown to be highly correlated with historical influenza-like illness records and allow for accurate prediction of influenza-like illness data several weeks before it becomes available,” say Hickmann and co.

There is a caveat, however. One problem is that the forecasts significantly underestimate the size of the tail end of the flu season. That’s probably because people tend not to return to the Wikipedia flu articles if they reinfected with another strain of flu, which is a significant source of the disease late in the season. “Since our model does not account for reinfection or multiple strains of influenza, the tail of the epidemic is not predicted well after the peak of flu season has past,” they admit.

Nevertheless, the work is an important step toward a system of prediction that is as detailed and well-founded as weather forecasting. One useful feature of their method is that it shows when the model deviates from the ground truth data. That allows it to be tweaked in real time to take account of these differences, just like a weather forecast.

Disease forecasting is a science in its infancy but it has the potential to drastically improve the medical world’s level of preparation for epidemics. The rough estimates that medics have had to work with until now often lead to significant levels of over- or underpreparedness.

That looks likely to change. And with the 2014-2015 flu season already upon us, the sooner the better.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1410.7716 : Forecasting the 2013–2014 Influenza Season using Wikipedia

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.