China’s Growing Bets on GMOs

How will China get enough to eat? More than 1.3 billion people live in the world’s most populous nation, and another 100 million will join them by 2030. China is already a net food importer, and people are eating more meat, putting further demands on land used to grow food. Meanwhile, climate change could cut yields of crucial crops—rice, wheat, and corn—by 13 percent over the next 35 years. Mindful of these trends, China’s government spends more than any other on research into genetically modified crops. It’s searching for varieties with higher yields and resistance to pests, disease, drought, and heat. The results are showing up in the nation’s hundreds of plant biotech labs.

Right: This soybean plant has been genetically modified in an effort to produce more and higher-quality soybean oil.

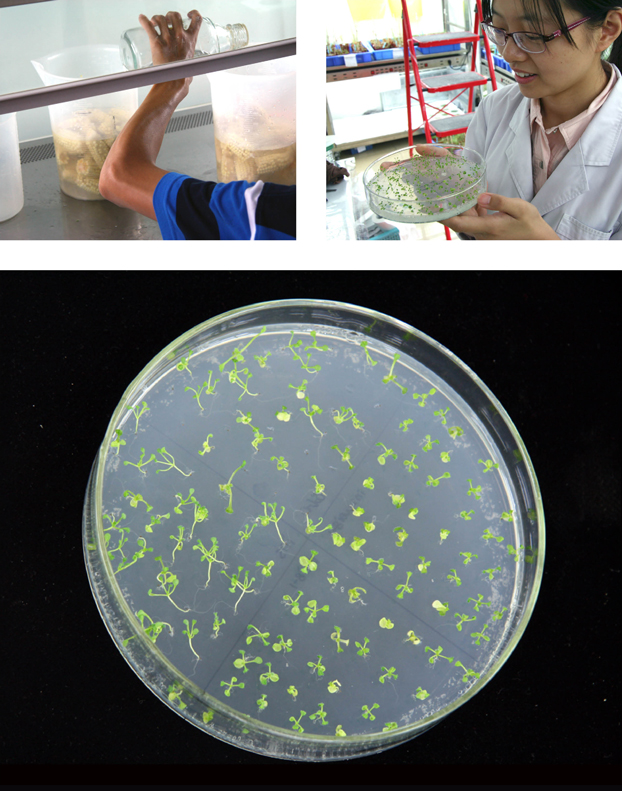

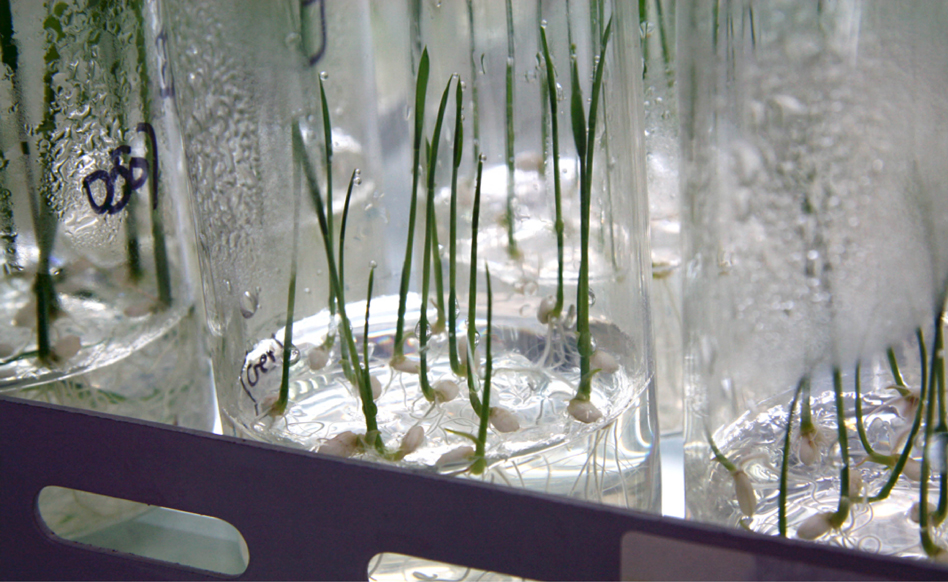

Right: In a tissue culture room, researcher Bing Wang works on seedlings of Arabidopsis, a fast-growing weed commonly used as a model organism by plant biotech researchers.

Bottom: This petri dish is full of nine-day-old Arabidopsis seedlings grown at 28 °C, a relatively high temperature. The goal of the experiment is to see how heat alters the plant’s hormonal behavior and growth patterns. Such experiments add to basic knowledge that can guide future approaches to GMOs, including varieties that can better withstand the hotter heat waves expected in the future.

Left: Caixia Gao shows off a strain of rice that has had genes removed so that it grows far shorter than typical rice, which can be seen to the left and right. Gao is investigating whether such diminutive rice strains devote more energy toward producing seeds—the food—and less toward leaf material.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.