Twitter Data Mining Reveals America’s Religious Fault Lines

Religion represents one of the most powerful forces at work in shaping today’s society. So there is a great deal of interest in understanding how religion influences people’s views and tolerance of each other and how this affects other aspects of society such as economic growth.

One potential tool in improving this kind of understanding is the Internet, where religious views flourish. In particular, social networks have expanded rapidly in the last few years, playing an increasingly important role in spreading opinions and information in areas as diverse as politics, sport, science, and so on. However, the role that social networks play in religion has been relatively poorly studied.

Now Lu Chen at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio, and a couple of pals have analyzed more than 250,000 Twitter users in the U.S. who have declared an affiliation with religions such as Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, Buddhism, and Judaism. The results provide some curious insights into the nature of religious activity on Twitter and how these groups of self-declared users differ from one another.

The team began by filtering the biographies of Twitter users in the U.S. using keywords associated with various different religions. That produced a data set of more than 250,000 users from seven different groups: atheists, Buddhists, Christians, Hindus, Jews, Muslims, and undeclared. Christians were by far the largest group with over 200,000 users, while Hindus were the most poorly represented with only 200 users.

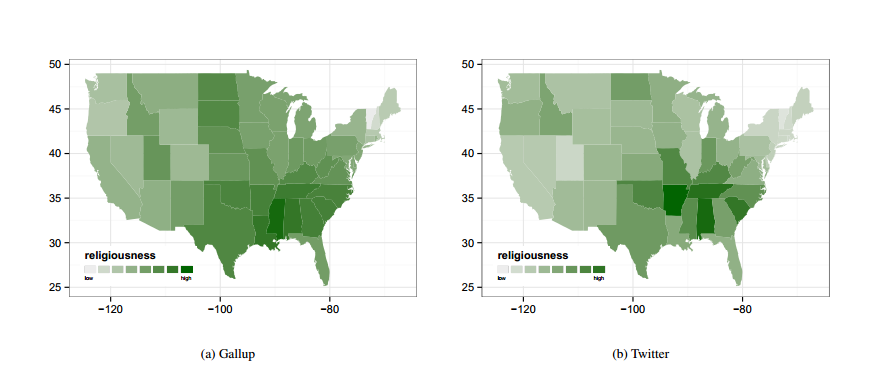

Chen and co then calculated the religiousness of each U.S. state according to their data. They then compared this to a “ground truth” Gallup survey of religiousness. They say the data sets demonstrate a respectable level of agreement. “They agree on 11 of the top 15 most religious states (e.g., Alabama, Mississippi, and South Carolina) and 11 of the top 15 least religious states (e.g. Vermont, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts),” they say.

However, there are some important differences. According to the Gallup poll, Utah is the second most religious state in the U.S., but one of the least religious states in the group’s Twitter data set. That is almost certainly because the group did not filter the biographies for Mormonism, the dominant religion in Utah.

Chen and co go on to ask what kind of information each group tends to tweet. To find out, they collected all of the words that appear in more than 100 tweets in each group and ordered them by frequency of use. That gives them the words that are most positively associated with each religious group.

For Christians, these include words such as Jesus, God, Christ, Bible, gospel, pray, and so on. By contrast, the words most associated with atheists include science, evolution, evidence, religion, Republicans, abortion, and so on. In general, Chen and co say the words most strongly associated with different religions tend to be focused on the nature of the religion itself.

This could have important implications for society. “If our observations were to hold in a broader context, it could be seen as good for society that followers of religious groups differ most in references to religious practice and concepts, rather than in everyday aspects such as music, food, or other interests,” say Chen and co.

The team also asks who people in these groups are most likely to follow. Unsurprisingly, members of one religious group are much more likely to follow members of the same group than members of a different group. “Following someone of the same religion is 646 times as likely as following someone of a different religion,” say Chen and co.

It is also possible to work out the most popular accounts followed by members of each group, and this reveals some interesting fault lines. For example, the most popular account followed by Buddhists is @Dalaillama , while the most popular among atheists is @RichardDawkins. All the religious groups are likely to follow @BarackObama, reflecting their American heritage.

One important question that this kind of work raises is to what extent the behavior on Twitter is indicative of the real world. One potential problem is that Twitter users themselves are not entirely representative of the general population — they tend to be young, male, and urban. What’s more, all of the selected Twitter users have a self-declared interest in religion, making them more likely to be highly religious compared to most users. Just how this biases the data isn’t clear.

Nevertheless, Chen and co have made an interesting start in teasing apart the behavior of religious users on Twitter. And in pursuing this line of research, there ought to be plenty more low hanging fruit.

For example, analyzing the sentiment displayed in tweets from users of different religions could be revealing, and Chen and co certainly have plans to study these kind of ideas in more detail. “In future work, we hope to gain clues as to what makes a religion stand out, e.g., when it comes to providing emotional stability or dealing with personal setbacks,” they say.

Another interesting possibility is to study tweets in regions of the world that are devastated by religious conflicts. Obvious examples abound. Of course, this kind of work is complicated by all kinds of additional factors, not least of which is language.

Whatever the direction of future research, it is clear that religion and social media are likely to have an important ongoing relationship. As Chen and co point out, much religious activity focuses on the spreading and replication of religious ideas. In other words, social media and religion are ideally suited. That suggests an interesting evolution in the way religions exploit Twitter and other social media platforms—yet another dynamic to study.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1409.8578 : US Religious Landscape on Twitter

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.