The Murky World of Third Party Web Tracking

One of the murkiest areas of Internet commerce is the international trade of personal information gathered by certain companies who monitor our behaviour online. This kind of third-party data gathering is ubiquitous on the web thanks to the humble “cookie”.

A cookie is a small piece of data that a website loads onto your browser. Every time you visit that site in future, the browser sends that cookie back to the server so that the website can correlate this with your previous activity.

Cookies are an essential part of Internet commerce and also used in analytics. They are safe in the sense that they cannot carry viruses. But where safety is less clear is that they make it possible to build up a picture of your online activity, particularly when a website contains trackers belonging to a third party, such as an advertiser or analytics provider. These third party trackers are often able to piece together your activity on several different websites and when that happens the question of privacy becomes more acute.

That raises some important questions. How do these companies use the data they acquire, where is it stored and who has access to it? The law covering this kind of activity is a particularly murky shade of grey in many parts of the world so the answers are not at all clear.

But an important step to increasing transparency is to ask what companies are involved in this kind of data collection in the first place and where do they carry out their trade.

Today, we get an answer thanks to the work of Marjan Falahrastegar at Queen Mary University, London, and a few pals who have spent some time tracking the trackers in countries all over the world. The picture they reveal is of a global ecosystem of third-party tracking showing how vast this practice has become.

Their approach is relatively straightforward. Access a website and it will load cookies that can then be studied. Typically, a website will load cookies from the domain that is shown in the browser’s address bar but will also load cookies from other domains belonging to advertisers and analytics companies. These third party trackers can be spotted because their domain does not match that of the accessed website.

Falahrastegar and co created a browser extension that automatically downloaded this information for each website and then cleared the cookies before accessing another website. They then accessed the websites of the top 500 most popular websites in countries round the world.

One practical problem they faced is that the cookies can depend on the geographical location of the browser. So a browser in the UK accessing a site in China might end up with different cookies to a browser based in Beijing.

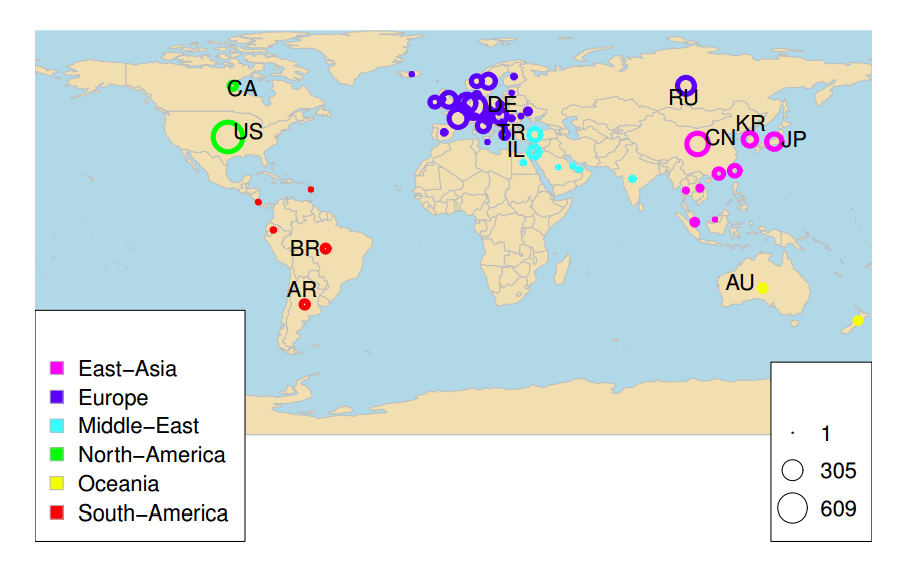

To get around this, Falahrastegar and co used a global research network called PlanetLab which has nodes in many countries around the world and so allows access to local websites as if the browser were locally based.

In total, the team gathered data from 28 countries using PlanetLab nodes. And they found third-party trackers belonging to companies all over the world. For example, Google has over 40 third-party domains used all over the planet, Microsoft has 19, eBay 7 and so on. There are plenty of less famous names using many third-party domains, such as knet.cn, iponweb.net and sina.

The results provide a fascinating insight into the nature of third-party tracking services. The team found for example that the distribution of third parties tracking data in Europe, East Asia, Oceania and South America was more or less even. By contrast, the number of third parties tracking data in Turkey and Israel was much larger.

The origin of these third parties is interesting to. Third parties from Germany and Russia are particularly prevalent in tracking users all over the world. And third parties from the US are embedded in popular websites in the Middle East.

Falahrastegar and co say there is a good reason for this. They point out that the distribution of third parties reflects the legal constraints in operation locally. For example, in the European Union and Australia there are specific laws about the information that can be collected and how users must be notified. So it is no surprise that there is a fairly even distribution of third-party trackers in these places.

By contrast, there are no specific laws in countries like China and Turkey, where third-party trackers appear to be more rampant.

In addition, the law is complex in places like the US and Russia, while Germany has yet to enact European laws on ePrivacy so the situation is ambiguous there as well. This explains the high presence of third party services in specific countries like the US, Germany and Russia, say Falahrastegar and co.

The bigger picture is that in many parts of the world, the gathering of personal data is poorly policed, if at all. “Our observations suggest that privacy regulation, particularly in the area of cloud computing, requires more attention from the regulatory community,” conclude Falahrastegar and co.

The prospect of the international regulatory community gripping this nettle seems remote. But it does open the possibility that some other organisation may step in to increase transparency in this area. The first step in understanding how personal data is used is in revealing the details of what is going on.

Falahrastegar and co have taken the first step now others will have to pick up this ball and run with it.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1409.1066 : Anatomy of the Third-Party Web Tracking Ecosystem

Deep Dive

Computing

How ASML took over the chipmaking chessboard

MIT Technology Review sat down with outgoing CTO Martin van den Brink to talk about the company’s rise to dominance and the life and death of Moore’s Law.

How Wi-Fi sensing became usable tech

After a decade of obscurity, the technology is being used to track people’s movements.

Why it’s so hard for China’s chip industry to become self-sufficient

Chip companies from the US and China are developing new materials to reduce reliance on a Japanese monopoly. It won’t be easy.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.