The New Chinese Factory

With its medieval canals and carefully preserved downtown, the eastern Chinese city of Suzhou might have been a quiet burgh compared with neighboring Shanghai. But in 1994, the governments of Singapore and China invested in an industrial development zone there, and Suzhou grew quickly into a manufacturing boomtown.

Singapore-based Flextronics, one of the largest global contract manufacturers, built factories there, initially to make small consumer electronics. Those products were relatively simple to assemble in great numbers, making them well suited to China’s then plentiful and inexpensive labor force. But by 2006, labor, land costs, and competition were rising, and Flextronics’ margins were shrinking.

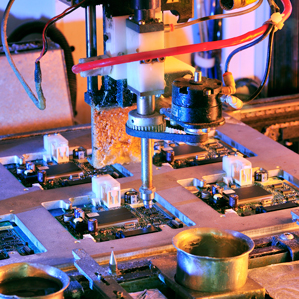

The company refocused its two Suzhou factories on more complex manufacturing, aiming to make higher-priced machines for the aerospace, robotics, automotive, and medical industries. To do so, Flextronics has invested in automation, increasingly precise manufacturing, and improved worker training, all while learning to manage a complicated component supply chain.

Today, these more complex goods make up 72 percent of Flextronics’ Suzhou output. Finished products include printed circuit boards, hospital ultrasound machines, and semiconductor testing equipment so complex each machine requires more than five million parts and retails for $2 to $3 million.

It’s a model the Chinese government has pushed manufacturers to adopt, focusing government investment on advanced industries and boosting R&D spending on science and technology. According to data from the U.S. National Science Foundation, between 2003 and 2012 Chinese exports of high-tech products climbed from just over $150 billion to more than $600 billion, making China the largest exporter of such products in the world. Ernst & Young forecasts that by 2022, the country will produce a third of the world’s electrical goods.

On a recent visit to one of Flextronics’ two Suzhou plants, the increasing use of automation is quickly apparent as an automated trolley delivers parts to workers up and down an assembly line, stopping if someone crosses its path. Nearby an LCD wall panel shows the progress of various items moving through quality testing. In the past, workers ticked off boxes on paper forms and entered the results into computer spreadsheets—a time-consuming process fraught with the potential for errors. Now automated data about progress down the assembly line is collected in real time.

Clients can track the data on apps designed by Flextronics. When there’s a disruption due to anything from delivery problems to labor strikes, another app, Elementum, taps into the extensive Yangtze Delta region supply chain, showing customers alternate scenarios for sourcing parts or rerouting production to any of the company’s 30 other mainland plants.

Such services are part of Flextronics’ push to show customers that after years making goods to the specifications of demanding customers like General Electric and Philips, it has more to contribute. Today Flextronics offers its own design and engineering services, consulting on both finished products and ways to improve the manufacturing process.

Flextronics has sometimes expanded its high-end work by going into business with customers. About four years ago, Steven Yang, general manager of one Suzhou factory, led a company investment in a French firm designing a small robot to be used for university research and, potentially, therapy for children with autism. Working from their prototypes, Flextronics designed a manufacturing process that has in six months delivered 1,400 of the robots, which use sonar and facial recognition technology and can be programmed to listen and to speak.

James She, an operation manager in charge of the robot line, says volume has more than doubled since the initial run in the final quarter of 2013, and he expects orders to rise, especially in Asia, where health care and elder care are fast-growing industries. “The robot can be a member of a family in the future,” She says.

Flextronics has pursued automation wherever it has the potential to reduce labor costs and errors. For example, automated optical testing equipment, which checks that the circuitry on printed circuit boards is correct before they are installed in other machines, has cut the number of workers on the inspection line from six to two.

But as product cycles speed up, it doesn’t always make sense to make large investments in robots. Humans are still more flexible. “The time you have to spend changing the machine means it’s not always worthwhile to automate,” says Es Khor, an engineering director at the factory. “When we look for where to automate, we also look for process-specific, rather than just product-specific, tasks.”

So while the French robot line may be creating the health-care assistants of the future, at the moment the robots are being assembled by 28 workers wearing navy blue uniform smocks, mostly young men from rural China. All of them have had at least three months of technical training, and the French company provides performance-based bonuses and organized leisure activities in hopes of reducing turnover and retraining costs. Flextronics has also upgraded its dormitories, built worker break rooms, organized hiking trips and choral groups for employees, and staffed counseling hotlines, all with a view to retaining increasingly expensive, and highly trained, labor.

Twenty-year-old Lan Wenzhi has been working on the robot production line for six months. His job is fastening in tiny screws that hold the battery inside a small box. He has a high school diploma, a smartphone, and a fondness for American movies. His monthly average take-home pay after taxes, including overtime, is about 3,500 yuan (about $570). Factory general manager Yang says that with rising wages in this part of China, labor has increased from about 2 percent of the factories’ costs in 2005 to about 4 percent today. But it’s still relatively small when compared with the 80 to 85 percent of the operating budget spent on materials.

For Yang and Flextronics, the goal is to take advantage of nearly two decades of manufacturing experience to make their factories centerpieces of innovation, not just cheap places to make things.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.