The first computer that Leslie Lamport encountered in his first year at MIT was an IBM 704. The summer before, he had learned how to mount and switch external storage memory tapes on such a machine in a part-time job at Con Edison in New York. “In my spare time, I learned to program the computer and made some little programs,” he recalls.

Lamport graduated from MIT in three years with a degree in mathematics, and then he earned two more math degrees: a master’s in 1963 and a PhD in 1972, both at Brandeis University. He built a career in computer science at Compass, SRI International, Digital Equipment, and Microsoft. This June, the Association for Computing Machinery bestowed on Lamport computing’s top prize, the Turing Award. It came with a $250,000 check.

As was clear in those early experiences, Lamport always sought to roll up his sleeves and assess computers’ practical, everyday problems.

In seminal work published in 1978, Lamport set out many of the key concepts in distributed computing, which laid the groundwork for the systems that enable computers to work together across space and time, despite occasional failure. Algorithms and protocols he developed—including logical clocks, which capture chronological and causal relationships in a distributed system, and the fault tolerance protocol known as Paxos—would help make the World Wide Web possible. Today, technologies ranging from search engines to 911 call centers to air traffic control systems rely on his breakthroughs.

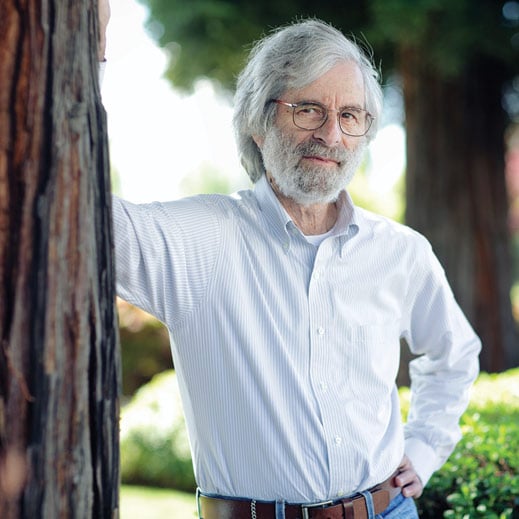

Lamport, who lives with his wife in Palo Alto, California, is humble about his work.

“I’ve been credited with initiating the theory of distributed systems and I feel embarrassed by that, because I don’t see a theory there,” he says. “There’s nothing there like Newtonian mechanics or relativity, something in the science sense you’d call a theory. But in looking at all these little pieces of work I’ve done, although I didn’t create a theory, I did, with the help of others, create a path that other people have since followed—and turned into a superhighway.”

Lamport still dreams of an underlying theory that would tie together all his work on the way simultaneous processes affect one another in computer systems. But on a typical day, he’s more intent on encouraging engineers to employ the algorithms and tools he’s developing at Microsoft Research in Palo Alto.

“It’s a great lab, with great colleagues, and a great company that really appreciates research,” he says.

The feeling is mutual.

“Leslie has done great things not just for the field of computer science, but also in helping make the world a safer place,” Microsoft founder Bill Gates said in a Microsoft tribute. “Countless people around the world benefit from his work without ever hearing his name.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.