How Yahoo Research Labs Studies Culture as a Formal Computational Concept

The study of online social networks has revolutionized the way social scientists understand human interaction on a grand scale. It is based on the assumption that the fundamental unit of interaction is the social tie that exists between two individuals. This tie can be a message that one person has sent to another, that one person follows another, that one person “likes” another and so on.

These social ties are the atoms of social network structure. And much of the research on social networks has focused on how these atoms join together to create complex networks of interaction.

Much less thought has been given to the atoms themselves, whether they fall into categories themselves, whether different atoms have different social properties and how combining atoms of different types might be indicative of entirely different relationships.

Today, Luca Maria Aiello at Yahoo Labs in Barcelona, Spain, and a couple of pals, change that. They tease apart the nature of the links that form on social networks and say these atoms fall into three different categories. They also show how to extract this information automatically and then characterize the relationships according to the combination of atoms that exist between individuals. Their ultimate goal: to turn anthropology into a full-blooded subdiscipline of computer science.

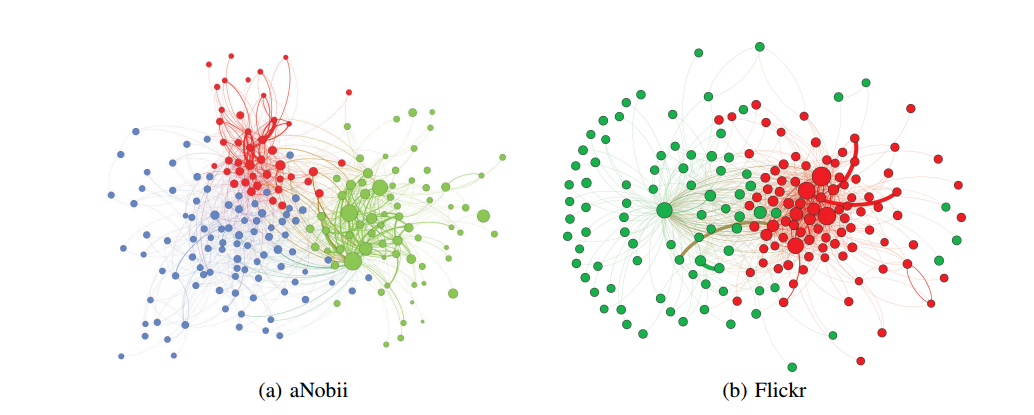

Aiello and co used two data sets from a pair of large social networks. The first consists of over 1 million messages sent between 500,000 pairs of users of the aNobii social network, which people use to talk about books they have read. The second is a set of 100,000 anonymized user pairs who commented on each other’s photos on Flickr, sending around 2 million messages in total.

The team analyzes these messages based on the type of information they convey, which they divide into three groups. The first type of information is related to social status; messages displaying appreciation or announcing the creation of the social tie such as a follow or like. For example, a user might say a photograph is “an excellent shot” or say they’ve followed somebody or acknowledged attention they’ve got by thanking them for visiting a site.

The second category of information involves social support of some kind. The main purpose of a message that falls into this category is to greet or welcome someone to a website, to explicitly express affection or to convey wishes, jokes and laughter.

The final category of information is an exchange of knowledge. Messages that fall into this category share information and personal experience, or ask for opinions and suggestions, or display knowledge of a particular field.

Aiello and co then develop an algorithm that automatically categorizes the messages sent between individuals according to the content they contain and their similarity to messages of the same type.

Finally, they evaluate the results of the algorithm by asking human editors to assess a sample of 1000 randomly selected messages from each website and label them according to the three categories. They then compared the human choices with the algorithms and found good agreement.

The results of this analysis allow them to work out how often people use the different modes of communication and also how they transition from one to another during a conversation.

They find that in aNobii, the most frequent interactions involve status giving where the archetypal message is “nice library”, referring to a user’s collection of books.

By contrast, Flickr users communicate in a different way. “In Flickr the proportion is very balanced instead, with no domain being predominant on average,” say Aiello and co.

More interesting is the way that social ties evolve over time. Aiello and co say that status exchange is particularly common in short conversations and at the beginning of longer ones. However, the conversations rapidly evolve into a mix of knowledge exchanges and social support. “It thus appears that status exchange serves to set the foundation for the future relationship, feeding to the interactional background after the tie-formation stage,” say Aiello and co.

That’s a fascinating study that provides a new way of looking at social ties as strings of interactions. In a way, it changes the atomic theory of social ties into a kind of string theory.

Aiello and co clearly think this should lead to plenty of new insights and they are optimistic about the future. “The ultimate goal of such analysis is the unpacking of “culture” as a formal, computational concept,” they say. And they think of the patterns of strings of interaction as a kind of grammar of society. “We hope our work provides yet another step towards a truly computational understanding of human societies.”

That’s an ambitious goal– a truly computational understanding of human society. Both fantastic and a little frightening the same time.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1407.5547 : Reading the Source Code of Social Ties

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.