In December 1890, the Boston Herald published a string of editorials critical of MIT. The Herald claimed that MIT’s standards were too high, leading to a low graduation rate and the physical and mental breakdown of its undergraduates. The newspaper even called for a committee of physicians to evaluate whether the Institute was putting too much strain on its students.

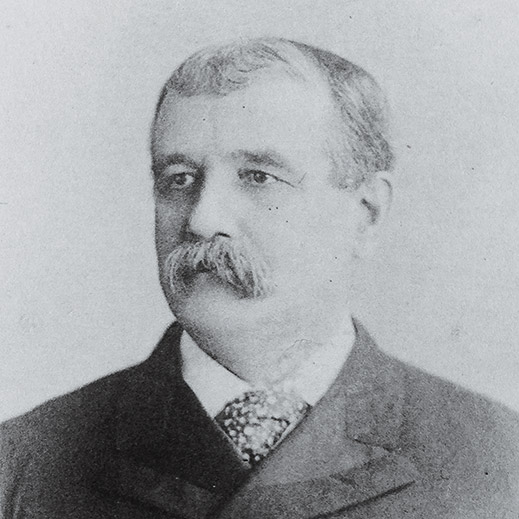

MIT’s president at the time, Francis Amasa Walker, did not take the criticism lightly. In a letter to the editor, he called the claims unfounded, demanding evidence to support them. He referenced a personal letter he had written to every graduate of the classes of 1885 and 1886, in which he asked them whether the work at the Institute was more than should be required: “In only three cases did the persons replying admit that there was the least ground for complaint on this score.” More than three-quarters of the students in those classes never graduated, however, so Walker might have received a different response if he’d also written to them.

Still, nearly all of the replies to Walker’s letters affirmed that the academic rigor should be upheld. Augustus Stoughton, Class of 1886, called the workload entirely suitable for a young man of good health who “has had proper fitting” for the Institute, adding, “I should be extremely sorry to hear of a diminution of the amount of work required of your students, knowing that a lowering of the standard of the school would be a direct result.”

That was certainly the way Walker saw it. “I believe there is not a member of the existing faculty who would not rather see the Institute disbanded tomorrow, and its buildings delivered over to the city of Boston for a poorhouse, than commit the crime against scholarship and the treason to science which would be involved in conferring the degree of the Institute upon any man who had not thoroughly and well earned it,” he wrote in his letter to the Herald.

Almost a century later, in 1970, Patrick Conal Green ’70 documented alumni perceptions of the Institute for his thesis, surveying 11 alumni spanning classes from 1915 to 1965 about such questions as whether they felt prepared for the rigor of MIT and whether they received support from the faculty. The perspectives varied. Some alumni felt unprepared and overworked during their time at MIT; others said the workload had been manageable as long as they were focused. Joseph Harrington ’30 explained, “There was real pressure, but it was something you could cope with by a certain amount of hard work.”

Fast-forward to October 2012, when Lydia Krasilnikova ’14 composed a blog post for her part-time job at the admissions office that she titled “Meltdown.” Krasilnikova described her conflicted feelings about life at MIT. “Sometimes it feels like MIT drags your self-esteem over a jagged, gravelly rockface and stretches your happiness, your mental health, and the passion and energy that brought you here like an old rubber band,” she wrote. “There’s this feeling that no matter how hard you work, you can always be better, and as long as you can be better, you’re not good enough.”

Within a month, her post had 247 comments, many from students and alumni detailing their own experiences with stress and self-doubt. Others contacted Krasilnikova directly. MIT president Rafael Reif responded with both a comment on Krasilnikova’s post and a letter in the Tech that commended the outpouring of support. “It is not clear to me that there is a magic wand of institutional action that would address the issues that Lydia highlights, in ways that would be acceptable to the MIT community as a whole,” he wrote. Instead, he called on the community to “broaden and deepen” the conversation on stress at MIT and invited suggestions on ways to respond.

Meanwhile, the Tech addressed the issue in true MIT form: by surveying nearly 3,200 students in order to quantify stress and workload management at the Institute. Its “Under Pressure” special issue included interviews with students and administrators and provided data on sleep habits, which classes students find the most stressful, and a breakdown of how students divide their time among sleep, work, and play.

The difficult problem of stress at MIT is unlikely to abate anytime soon. But many take comfort in the fact that it’s shared. As Jessica Pourian ’13 wrote in her editor’s note in the Tech, “Remember—no matter how hellish MIT can get, we are a community. You aren’t alone.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.