Why Some Doctors Like Google Glass So Much

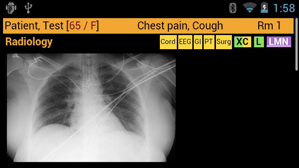

Kermit the Frog showed up in the emergency room at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston recently, complaining of chest pain. A quick tilt of my head showed me Kermit’s records—his EKG results, the radiology tests ordered for him, and his medical history.

Don’t worry, Kermit’s not really sick. The frog’s emergency room visit was just meant to illustrate how Google’s face-mounted computer, Glass, can let physicians quickly get up to speed on a patient’s situation without having to turn repeatedly to a computer.

Physicians in the hospital’s emergency department are in the midst of a pilot project using heavily modified versions of Glass to look up patient records. Emergency physician Steve Horng is spearheading the project, which offers Glass to all physicians in the department. “Emergency medicine is a very information-intensive specialty where even small nuggets of information available immediately really matter,” he says. “Having information one minute earlier can actually be quite life-saving.”

The experiment is one of many tests to see if face-worn computers can be beneficial for workers who need fast access to small amounts of information without taking their hands or even their full gaze away from other tasks. These efforts hint at the potential benefits, as well as the remaining challenges, of wearable computing in general.

Google isn’t the only company offering devices that meet these needs. For example, Epson sells a pair of goggles that help nurses see veins through a patient’s skin, and Vuzix produces head-mounted displays for the defense industry that can identify friendly forces and more (see “Hands-On with the Vuzix M100, a Google Glass Competitor”).

The emergency room team at Beth Israel has four pairs of Glass, which can be picked up at the beginning of a shift. After a nurse has checked a patient in, a doctor uses Glass to scan a QR code on the outside of the patient’s room. That simply tells the device which room number the doctor is entering; the custom app then looks up patient records on the hospital Wi-Fi network and displays the records to the doctor on a small prism in front of one eye.

The amount of information available through the app is limited, and it’s not possible to do complicated searches or any data entry with gesture and voice commands. But for emergency medicine, the high-level facts are useful, says Horng.

San Francisco-based Wearable Intelligence developed a custom application for Glass that blocks all the device’s social-media features and locks it to the hospital’s Wi-Fi network. Wearable Intelligence has developed other custom applications for industrial uses of Glass, such as one that provides real-time contextual information for oil and gas workers.

While Glass has its skeptics (see “Glass, Darkly” and “Google Glass Still Needs a Killer App”), there is some evidence the technology can be helpful in industries like these. At a recent event hosted by Google’s Cambridge branch, doctors from across the country came to show off how they’d thought of harnessing Glass for medicine. One presenter, Rafael Grossman, a surgeon based in Bangor, Maine, was the first person to use Glass during live surgery. He thinks the technique could help doctors teach new surgeons.

But for the pilot at Beth Israel, video is off the table, at least for now. “We wanted to stay away from anything that could potentially be misconstrued as leaking patient information, so until we had a case study and a good foundation, we purposely stayed away from enabling the video feed,” says Horng.

Clearly, Glass still has limitations. When I visited Horng at Beth Israel, a collaborator from Wearable Intelligence was testing out a new external battery pack for the device. Without the extra boost, Glass can last about two hours running the processing-intensive medical app, says Horng. That’s inadequate given the eight-hour shifts in the emergency department.

Like people in the wider population, some doctors doubt Glass’s usefulness. Emergency physicians in general are very technology savvy, Horng says, but they vary in their enthusiasm for the pilot project. “You’ve got the really early adopters that will try anything and just like new technology, and then you’ve got the other side that just refuses to get away from their clipboard, and so they are never going to use it,” he says.

But plenty of doctors seem excited, and they do not see Glass as a barrier to patient-doctor interaction. In fact, says Karandeep Singh, a nephrologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, they believe Glass could help improve it. “The advent of electronic health records has significantly changed that [doctor-patient] relationship,” he told the audience at Google’s Cambridge event. A lot of times, doctors equate looking at electronic records with seeing patients, said Singh: “Some of the art of medicine has been lost.” Glass offers a way to look up important patient data without breaking contact at the bedside, he said.

In the next version of the Glass app used at Beth Israel, the team plans to add voice commands, probably using a non-Google voice recognition engine. “Right now Google’s voice recognition isn’t as resilient as we would like,” says Horng.

The limitations of the Glass interface also represent a new area for potential innovation. “The use of mobile devices and all the opportunities that that opens up in clinical care create new needs on the informatics and algorithms side,” says David Sontag, a computer scientist at NYU, who is collaborating with Horng. “Only a small amount of information would be visible to the clinician. There simply aren’t that many pixels to display on, and time is of the essence.”

What will make Glass and other wearable devices more useful will be algorithms that can get the right data to doctors at the right time, says Sontag. “They are simply even more important now in the context of mobile devices.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.